Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Educating your sense of smell would seem to be a major challenge, especially since the resulting creation is usually reduced to its cosmetic dimension or role as a consumer product. However, there are different paths people can take to explore the sense of smell: the desire to understand its therapeutic qualities, curiosity about raw materials, and approaches focused on the theoretical, historical and aesthetic aspects. They form a broad landscape inhabited by amateurs from different horizons: what options are currently available to these fragrance aficionados so they can nurture their passion?

The sense of smell between the pages

The influence of the sensibilities inherited from the 18th century led to an initial approach to expressing scents in the work of Proust, Colette, Huysmans, Baudelaire and Süskind, to name but a few. The publication of Le Parfum in the Que sais-je collection written by Edmond Roudnitska in 1980 crystallised academic interest in the subject.. Michael Edwards shone the spotlight on the words and intentions of perfumers on a larger scale with his 1996 book Perfume Legends: French Feminine Fragrances. But the work that demonstrated how the sense of smell could serve as an object of theoretical study in its own right was The Fool and the Fragrant by the historian Alain Corbin. Published in 1982, it opened the door to research undertaken by Annick Le Guérer, Rosine Lheureux and, in the philosophy field, Chantal Jaquet. Perfume criticism also emerged with Luca Turin’s 1994 book, offering a new perspective on fragrance creation. However, it wasn’t until 2006 that the New York Times included Chandler Burr’s reviews in its columns.

Since then, the increasing number of publications has reflected the growing popularity of the subject: from Jean-Claude Ellena’s The Diary of a Nose to The Big Book of Perfume, but also The Essence: Discovering the world of scent, perfume and fragrance, and Robert Muchembled’s Smells : A cultural history of Odours in Early Modern Times, fragrance aficionados now have access to wide-ranging, valuable knowledge at the turn of a page. A more playful medium emerged in 2019 with the launch by perfume expert Anne-Laure Hennequin of the Master Parfums game, which combines general knowledge questions about perfume with olfactory challenges.

Perfume online

But what really popularised a new approach to creation were the blogs that sprung up in the 2000s as well as the emergence of niche perfumery: “Awareness of the importance of the sense of smell in my life took the form of a quest for identity, for ‘my’ perfume. At Le Bon Marché, I discovered brands I had never heard of: I wanted to find out more, and came across Auparfum, which has become my go-to,” recounts Anne-Cécile, a perfume lover and head of digital at a Parisian museum. Certain sites have expanded, such as Basenotes, Now Smell This, Bois de jasmin, Auparfum and Fragrantica. But perfume discussions have generally moved to social media, as confirmed by Raphaëlle, a human resources consultant: “I came across the En Quête de Parfum section on Auparfum and typed in my search. The community came up with lots of suggestions of creations for me, which produced a sort of olfactory craving. Then I found a few enthusiasts on Twitter and ended up, in a really natural way, meeting them in Paris. Since then I’ve joined a group on Discord, which we use to communicate regularly.”

While influencers on Instagram and Youtube mostly stick to recommendations that border on advertising, some of them, such as Olfactiveducation, do spread cultural facts and figures and provide access to discussions with professionals, like Café des Nez on Passionnez, The Perfume Guy and The Aetherialist account.

The quest to acquire knowledge of perfumery raw materials, generally hard to find for the general public, has been made much easier with the digital tool ScenTree, which Nez has now partnered: with its classifications based on olfactory descriptors, it provides a range of helpful information for each ingredient, including main components, stability, botanical origin, extraction and regulations.

Online conferences, serving as classes for a wider audience, have taken off since Covid restrictions came into effect; the Osmothèque proposes sessions tackling different topics such as the history of perfumery, raw materials and leading perfumers. Other positive initiatives have emerged. One example is Christophe Laudamiel’s idea of opening a Patreon account where he offers five subscription types for people to explore the perfumer’s world, his thoughts and his creative process. Podcasts are also gradually appearing, with offerings from brands including Cartier, Dior, Lutens and Fragonard, alongside the Perfume on the Radio, The Sniff Podcast and, recently (in French), Podcasts by Nez

Perfume as cultural object

However, educating the nose cannot only be theoretical: practice is essential. As the first point of access, traditional fragrance stores unfortunately tend to reduce the product to the brand, consigning its olfactory dimension to the background. They thus maintain the cliché of perfume as a superficial fashion accessory: “When I was young, I wore Coco Mademoiselle with the impression that I was wearing Chanel,” laughs Anne-Cécile. The cacophony of sprayed scents adds to the difficulty of simply smelling without buying, an experience that is “not necessarily pleasant, since we know that the salespeople have to do their job.” So, for a long time, amateurs had to choose: to study professionally or be content with satisfying their curiosity by simply smelling the mainstream creations or fragrant plants around them.

Nowadays, they have a choice of other places dedicated to perfume. The Osmothèque is a unique and essential international archive where various lost or reformulated fragrances can be smelled – but is only accessible to the general public during open days or conferences. The Musée International de la Parfumerie (MIP) in Grasse takes a different approach. True to its cultural mission, it highlights the different trades in the industry, the functioning of the olfactory system, raw materials, the history of extraction, creation and production techniques, and the shifting relationship with perfume down the years. The sense of smell is invited into the more traditional museums in France with an initiative created by Constance Deroubaix, founder of In The Ere, which offers “innovative conferences and visits where the works are no longer approached solely through the prism of the eyes, the mind and the emotions, but also through the nose”: a new way of perceiving paintings and bringing perfume into the world of culture.

Temporary but significant events that tackle the sense of smell have flourished since the pandemic: for example, recently in Paris, the Cité des Sens at the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie, The Sensory Odyssey at the Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle and Avez-vous du Nez?, a series of conferences, meetings and workshops organised in November by Bibliocité in collaboration with the Nez collective.

Scented workshops

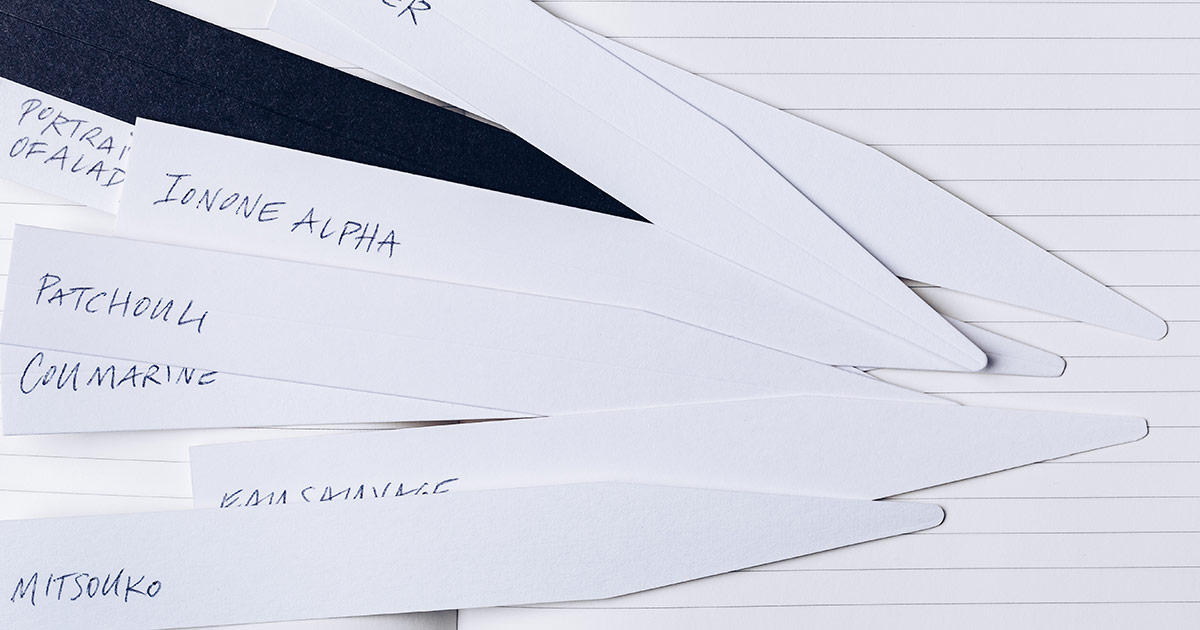

Perfume workshops offering a more practical experience are springing up everywhere, as the Auparfum test demonstrates, but are often still based on the promise of a tailor-made creation in a few hours. However, while handling fragrances can help to really get a feel for them, few of the workshops focus on simple learning; it would seem that, if you leave empty-handed, their interest is limited.

Others, however, stand out, such as Corinne Marie-Tosello’s events in Grasse: alongside a creation workshop and other theme-based sessions, her “Voyages en Terre de Parfum” are centred on a raw material, depending on the season. They were born of an interest in the plants, mixed with a perceptible love of transmission: “I entered perfume through botany. I studied at GIP and then became marketing manager for the independent perfumer Marie Duchêne, who had a real feeling for naturalness. This is what made me want to offer workshops on raw materials, in places where they are present,” particularly in the MIP gardens in Mouans-Sartoux. Creation of a composition brings to light the olfactory ties between the plant being studied and other notes that seem more distant. Participants are not always novices, however, even though they can attend at any age and without any qualifications. Corinne describes the atmosphere with enthusiasm: “Some professionals attend regularly. The discussions are often productive. It’s fascinating and complex, because you have to be accessible to everyone. But it creates a great group dynamic.”

Workshops can also be designed to create a bridge with other passions. Delphine Dentraygues set up her company Instantanez in Bordeaux and designs “oeno-olfactory” sessions where she puts wine and perfume together: “we start off smelling the molecules that we will then find in the wines. Using a different starting point, as well as retro-nasal olfaction, changes everything: the notes are not the same as the ones we smell on a blotter.” She runs more traditional perfume creation workshops which “introduce people to the different olfactory families, for people who want to understand their tastes, when they can’t find what they want on the market.”

Broader-reaching courses

Oenology is one of the paths followed by perfume enthusiasts who seek to perfect their olfactory perception, testifying to a lack of education for amateurs in the fragrance world. For a few years now, however, perfumery schools have been offering training courses over several days, or even several months, open to the general public, on the model of the ISIPCA summer school. They allow the rapid acquisition of the basics of olfactory culture, but are expensive and therefore not accessible to everyone. The audience is mainly made up of professionals looking to launch a scented product.

However, the health crisis, which has encouraged introspection and the emergence of the fear of anosmia, seems to have awakened the interest of a new public in these training courses, like Clémentine, an interior designer: “I had never considered studying perfumery, because I was always told that you had to be good at chemistry. So I gave up on my passion. But the lockdown made me refocus on what I really wanted. A friend gave me a book on perfume, and something clicked: I decided to enrol in a two-month training course via evening classes at ASFO, paid for in part with the state training allowance. I’m learning to put words to smells, I’m acquiring greater olfactory precision. I don’t know if I’ll make a career out of it, but I’m happy to be spending time doing this.”

For those who want to go further, Cinquième Sens, a pioneer in olfactory training since 1983, offers a fun and interactive perfume creation workshop as well as a more comprehensive one-day training session, where students study the physiology of the sense of smell, natural and synthetic raw materials, methods for memorising and classifying odours, the olfactory pyramid and the language of description. “This type of intensive day is attended by lots of people who come to confirm their interest in the field,” explains Cinquième Sens CEO Isabelle Ferrand. In addition, the centre provides longer and more specialised training courses. Various themes are explored, in French, some of which lead to professional qualifications.

Although the centre tends to cater for future or current perfumery professionals, “we also welcome enthusiasts, who account for 10% of those enrolled.” They come from all over France, or even from abroad. But the investment can be an obstacle: “That’s why we created the coworking space, which provides all the practical tools to train independently. The subscription fee is much more affordable, and the space allows amateurs –- who are in the majority – and professionals to meet.” Located in Paris’ 7th arrondissement, the space provides some 400 raw materials, 550 perfumes, a search engine and a library of over 200 books. A privilege reserved for Parisians, of course, but it is possible to place online orders for Olfactorium, boxes containing a variable number of raw materials.

Cinquième Sens has fifteen partners in different countries around the world as well as Passion Nez in Grasse. Up until now, visitors to the company’s site were mainly “foreigners, who come to acquire French know-how, linked to the status of Grasse,” explains Claire Lonvaud, who organises the Grasse workshops which are twinned with local visits. But since the pandemic, “there is a new audience: more French people, people undergoing professional retraining, and others who are interested in the therapeutic effects of odours: psychologists, speech therapists, and so on.”

On the very comprehensive 70-hour workshops combining theory and practice offered by the Grasse Institute of Perfumery‘s (GIP) since 2003, the audience is mostly from outside France, seeking to combine “the tourist aspect of Grasse with a real experience. We organise the workshops in line with the flowering seasons, as they include field visits to meet the various players (producers, companies, etc.),” explains Alain Ferro, the school’s director. “Europe represents 40% of the people we welcome; the Middle East and America account for most of the others, but we have visitors from 33 different countries,” adds Fabienne Maillot, who oversees these “short sessions” which, like the rest of the school’s courses, are given in English. The participants are mainly professionals from the luxury goods or cosmetics industry looking to improve their understanding of what constitutes one of their products, but also include thosewho are passionate about perfume and treating themselves to a wonderful gift.

With the Covid crisis and the impossibility of travel, GIP has developed interactive online courses, sending boxes of raw material boxes out beforehand. “We’re going to stick with the formula, because it allows people to save on the cost of travel and on-site accommodation, which inflates the fairly high price of the courses,” says Fabienne Maillot.

International, national and local

For Pierre Bénard, founder of Osmoart, olfactory education is a necessity at the international, national and local levels: “If we want perfume to be recognised as cultural and artistic, and no longer reduced to a consumer object, perfumers must go out and transmit their knowledge. It’s just not acceptable any more to see images of a kaffir lime when talking about bergamot.”

He thus proposes training courses based on the “systematics of odours”, a methodology involving “memorising and, especially, connecting notes in order to imagine and create accords,” with a classification in seven families where the links between the various elements are underlined. The courses, offered in English and by live video, include a box of raw materials shipped every month, followed by a four-hour course at the weekend. Students hail from all over the world, from France to the USA, Croatia and Lithuania, among others. They are professionals who want to focus on naturals as well as beauty bloggers, people undergoing retraining, and others who want to add an olfactory dimension to their work.

Pierre Bénard also runs courses for another public, whose primary interest is not in perfume: “but odours are always interesting and can be a vector of awareness.” For example, training courses for woodworkers, in partnership with Quintis, one of the world’s leading sandalwood producers and suppliers, offer a new approach to the topic. He also organises workshops and conferences for the general public around Lavaur in the Tarn in France, where he lives.

Olfactory culture is spreading further afield: in Spain, the Beauty Cluster Barcelona has created the Beauty Business School and its first long-termcourse on perfumery and its applications; in Los Angeles, the Institute for Art and Olfaction, founded in 2012 by Saskia Wilson-Brown, offers classes ranging from a few hours to several weeks for the general public, online or on-site, as well as conferences and exhibitions.

Access to the world of perfume and scents has thus expanded significantly in recent years. It is to be hoped that in the future more and more olfactory culture events will be offered to the general public, so they can reconnect with a sense whose social and psychological importance has been amply demonstrated by the pandemic.

Comments