Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Have you ever wondered what one could have smelled in the streets of London when Shakespeare’s plays premiered? Or above the canals of Amsterdam in its Golden Age? Which perfumes one could have inhaled in the 18th century inside the still glistening halls of the Fenice in Venice? Or yet what stench could have lingered on the newly opened boulevards in Haussmann’s Paris? Starting this year, the Odeuropa project will strive to constitute the first olfactory archive of Europe.

What are the key scents and olfactory practices that have shaped European cultures? How can this olfactory heritage be safeguarded and what is the point of such an undertaking? These interrogations are at the heart of the Odeuropa project, a multidisciplinary and transnational endeavor developed by a team of historians, linguists, art historians, perfumers, chemists, and specialists in the digital humanities and artificial intelligence. Originally from the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, France, Slovenia and the UK, these researchers will work together to elaborate an online database of the smells and fragrances that one could have smelled in Europe between the 16th century and the beginning of the 20th century. For each smell will be indicated its source, origin or place of occurrence, its qualities as well as the signification it might have carried across time. For, just as smells can have a tremendous importance in our personal history – Proust, are you there? –, they are also truly significant in our collective history and shared cultural identity. They constitute, according to the Odeuropa team, an olfactory heritage worth being preserved and highlighted1Although since 2003 UNESCO has started to acknowledge and classify the cultural Intangible Heritage of the world – in which have been inscribed in 2018 the skills related to perfume in Pays de Grasse –, olfactory heritage cannot be considered as part of it, as, despite its invisibility, a smell is still made up of tangible mater..

While the Covid-19 pandemic has caused a widespread wave of anosmia raising awareness around the value of our sense of smell, the Odeuropa project, which might have seemed a bit harebrained about twenty years ago, is actually part of a rising movement of revaluation of olfaction, and promotion of what can be called olfactory culture. For Marieke van Erp, a Language Technology and Semantic Web expert, and project manager, one of the objectives is to reveal the possibility for a critical use of this long-neglected sense. Proving the growing interest in all things olfactive, the consortium has already received a €2.8M grant from the EU, for three years of research.

Artificial Intelligence at Work

The first step of the project will be to program an artificial intelligence capable of identifying any mention of smell in hundreds of thousands of digitized texts and images. It will thus be possible to deal rapidly with a great volume of data, and to index the many scents and olfactory experiences mentioned within historical, scientific or literary documents – treatises about urbanism, botanic, pharmacy or medicine, press articles, historical accounts, trade registers, religious texts, recipes and formulas, autobiographies, novels and poetry, etc – in seven different languages (Latin, English, Italian, German, French, Dutch and Slovenian). The AI should also be able to identify potentially aromatic elements in visual artworks.

Teaching the AI will require to proceed to marking whether a text references a smell in order to feed the automatic learning algorithm. Thus it could learn, for instance, that in English a smell, whether it’s considered good or bad, can also be designated by the words “perfume,” “scent,” “odor,” “fragrance,” “aroma,” “effluvia,” “whiff,” “emanation,” “stench,” etc. It could also learn the adjectives used to modify a noun or noun group referencing something smelly, the verbs indicating the diffusion of a smell, and those describing the act of smelling. But the algorithm will first and foremost function thanks to phrases and expression patterns such as “it smells like X,” “the scent of Y,” “getting of whiff of Z,” etc. According to the first trials, this learning technique has proven to be more effective than simply using key words. The AI will then be able to search for excerpts referencing a smell, no matter the context or the exact formulation.

To identify olfactory objects within visual representations, the process will be rather similar. The algorithm shall receive a number of images in which will have been marked any potentially smelly element – a flower, a fruit, an animal, smoke – and its specific type specified – a lily or a rose, a pear or a pineapple, a horse or a cat, a fire smoke or an incense smoke, etc. Besides, the AI should also be able to identify noses in action, that is those which are actually smelling something. A subtle nuance that could reveal a lot about olfactory interests, likes, and dislikes in different eras and areas.

Nosing around History

The next steps will encompass organizing the information to allow research pertaining to the cultural heritage contexts of each smell, its temporal, geographic, and cultural specificities, its relationship with identity and society, etc. Of course, not all the scents will be of interest. Those that will enter the database are those which will appear to have had some major cultural or historical significance.

This could be, I imagine, the scent of the aromatic mix used by pest doctors to protect themselves, or the sooty effluvia spreading over Europe during the industrial revolution, or simple the aroma of popular dishes in various times and places. Maybe we’ll discover the smell of the salts commonly shown in films to revive unconscious dames, or maybe we’ll learn how the many sorts of tobaccos consumed all over Europe used to smell. For William Tullett, a British historian and member of the Odeuropa consortium, tobacco is indeed a particularly significant scent within European history, as it is intrinsically liked to the history of trade, colonization, health and sociabilities.

The project could also reveal more ad-hoc smells, associated with some major historical events. Wars in particular generate a form of “sensory overload” as wrote historian Mark M. Smith in his 2014 book The Smell of Battle, the Taste of Siege: A Sensory History of the Civil War. Thus has been mentioned the possibility to recreate, in the Odeuropa project, the stench of the battle of Waterloo. The smell of horses, of gunpowder, wet earth, sweat and blood, but also, why not, the eau de Cologne worn and loved by Napoleon. A first reconstitution, initiated by Dutch art historian Caro Verbeek, is already being presented at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam to echo the painting of the battle by Jan Willem Pieneman.

Besides the creation of the online database, about a dozen smells will eventually be reconstituted thanks to the work of chemists and perfumers. These reconstructions – done thanks to ancient formulas for example, or with the headspace technique which allows to identify the volatiles molecules emanating from a sample – will then be presented within museums and historical sites in Europe. They will constitute sensory entryways to history, allowing the audience to physically connect with the past and, literally, experience it.

A few history museums have actually already understood the potency of smells in visitor engagement. The first one to have relied on the smell to create a sort of ‘reality effect’ is the Jorvik Viking-Centre in York, followed by the Lofotr Vikingmuseum in Norway. Both have integrated typical scents to their historical reconstruction of viking houses and villages. Several French exhibitions these last few years have also tried to revive past smells such as Osiris, mystère engloutis d’Egypte at the Institut du Monde Arabe in 2016, in which could be smelled agapanthus, reed and incense, or the Parfums de Chine exhibition at the Cernushi museum in 2018 for which were recreated several traditional Chinese incense recipes. The Odeuropa project should encourage the development of these sensory museum practices in which scents are not simply accessories but genuine time machines, and entryways to the past and making of European cultures. Indeed, the essential is not to simply experience past odors but to understand the way in which they used to be perceived and interpreted – or even the way they were used. For, as historian of sensibilities Alain Corbin revealed in his 1982 groundbreaking book The Foul and the Fragrant, olfactory landscapes have evolved in history along with sensibilities – that is ways of sensing.

Between art and science

Although the scope of the Odeuropa project is rather unprecedented, it is nonetheless not without precedents as the idea of olfactory heritage has been embraced, in various ways, since the beginning of the 21st century. In 2001 in Japan, the ministry of the environment had listed and labeled 100 olfactory landscapes, natural, historical, and cultural sites which the smells were both distinctive, and worth being preserved. In 2016 the exhibition Scent and the City in Istanbul, organized by the Koç University’s Research Center for Anatolian Civilization, presented scents having had a particular significance in Anatolia since the Hittites2In addition, several archeologists have already attempted to reconstruct ancient perfumes.. One can also think about research projects such as Smell of Heritage by Cecilia Bembibre who got interested in preserving the smell of old books, as well as In Search of Scents Lost by Caro Verbeek, who offers to rediscover the scents that were once part of the art of the European avant gardes between 1913 and 1959.

A few contemporary artists have also attempted to preserve or revive past effluvia, as if they were the disembodied spirits of people (Jana Sterbak, Transpiration: Portrait olfactif, 1995), plants (Sissel Tolaas, Resurrecting the Sublime, 2018) or places (Carlos Ramirez-Pantanella, Madrid MDCXXXV, 2016). In addition, Spanish artist and architect Jorge Otero-Pailos taught, for several years, a class about experimental preservation at Columbia University, aiming at preserving the aromas which define the identity of certain heritage sites.

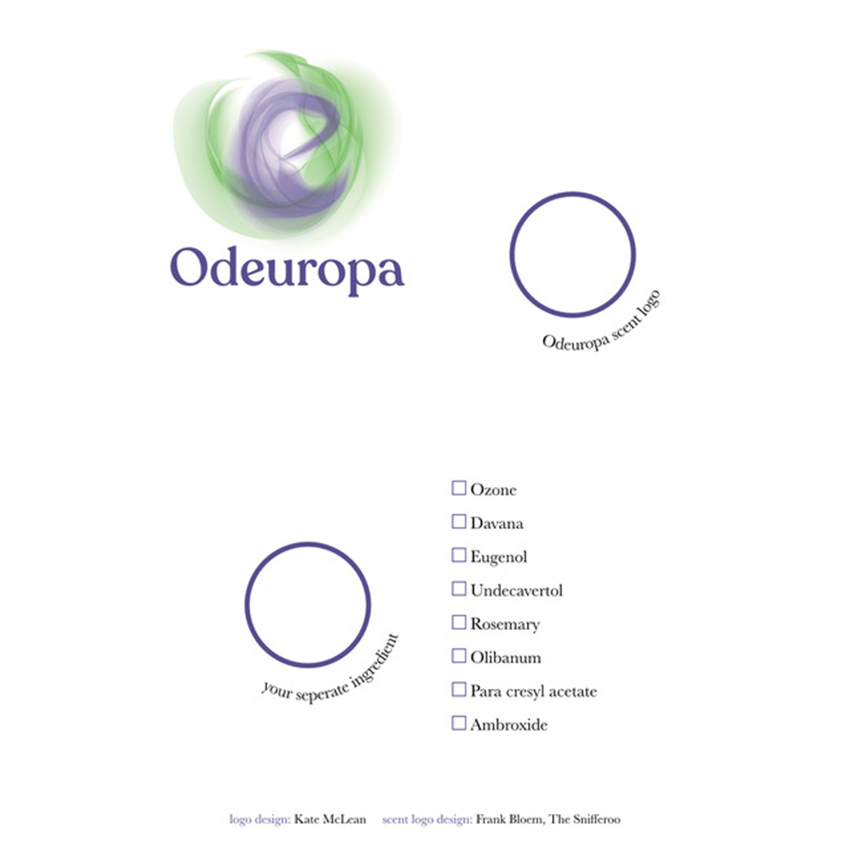

To sustain a connection to these olfactory art practices, the Odeuropa logo – an ‘O’ and an ‘e’ intertwined like two smoke rings – has been designed by artist Kate McLean, known for her smell maps, while a smell logo has been created by artist Frank Bloem. To imagine this olfactive signature he matched each letter from Odeuropa with a scent that has had a particular meaning in European history : Ozone, Davana, Eugenol, Undecavertol, Rosemary, Oliban, Paracresol and Ambrocenide. These words and materials might sound mysterious to many people. They will have to be discovered, along with the smells uncovered by the Odeuropa team, when museums reopen their doors to curious noses and we are allowed to breathe freely once again.

Main picture: Still Life with Cheese, by Floris Claesz. van Dijck, circa 1615. @Rijksmuseum – Source : odeuropa.eu

Comments