Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

From ylang ylang pickers’ exploitation in an article published in the French magazine Médiapart in 2023, to child labour in the harvesting of Egyptian jasmine highlighted in a BBC documentary[1]You can watch “Child labour behind global brands’ best-selling perfumes” on the BBC Youtube channel, and read the article from Ahmed ElShamy and Natasha Cox on its website in May, several scandals have weakened the fragrance industry recently – while the word ethics is repeated over and over by the perfume brands. Maybe one of the keys lay in the fair remuneration of the first links in the chain? What seems obvious is yet far from being the rule. We offer an analysis of this burning issue, published in the last issue of Nez magazine, which examines the different connections between money and perfume.

Behind the fancy words on raw materials in advertising, there are stories that some would like to forget. That of the colonial roots of the industry is one of them. Yet this history is essential to understanding the way the industry works today and must be recalled out of fairness to colonized peoples. Without them, perfumery as we know it would not exist. It isn’t only chemistry that allowed us to shift from costly creations reserved for the wealthy to a mass industry. The movement is global, as Sylvie Laurent argues in Capital et race, Histoire d’une hydre moderne [Capital and race, the history of a modern hydra] (Seuil, 2024): “Without the ‘cheap nature’ that is constitutive of capitalism, without slavery and the exploitation of American land (to which the unpaid labor of women in home countries must be added), Europe would have never entered the age of growth and technique.” Producing the quantity of naturals we know today has meant resorting to an exploited workforce, but also to fertile lands dominated by the West such as those of Madagascar, the Antilles and Guyana, or the island of La Réunion.

Some cultivated plants are endemic. Others have been introduced through experiments. In the manual Les Plantes coloniales utiles que l’on peut cultiver en France [The useful colonial plants that can be cultivated in France], published in 1943, the botanist Auguste Chevalier thus conceives colonialist exploitation as a means to “repatriate wealth”: “The French colonies of North Africa, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, have the bounded duty to concern themselves with meeting the needs of mainland France with these essences. […] The production of these hesperidic essences is not complicated: no costly equipment, a simple and easy process, the cheap labor of women and children.”

The historian Mathilde Cocoual has studied the case of Madagascar, where the industry of Grasse introduced the cultivation of ylang-ylang, vanilla, clove and cinnamon in the early 20th century: “There is a duality in this gesture: On the one hand, of course, there was the exploitation of local populations as well the harmful effects of colonization; on the other hand, perfume plants were a complementary resource for local farmers, often easier than working in mines,” she explains. Migratory, cultural and religious upheavals, a lasting modification of lands, villagers requisitioned willingly or not, and bad living conditions on estates are part of the colonial footprint. During the decolonization period in the 1960s, lands were abandoned with no aid or financial compensation; perfume plant farms ended up being bought out by other companies.

A legal price, an ethical price

What is the situation in 2024? While it is difficult to know the income of harvesters and farmers, which fluctuates a lot – and because the subject is taboo – and while conditions of access, intermediaries and the specificities of each material make the control of a fair compensation for the first link in the chain complex, the situation is precarious enough to justify protest movements like those carried out by French farmers in January 2024. When the geopolitical context is complicated, the situation is even more disastrous. In an article published by Médiapart in March 2023, Florence Loève denounced “behind Dior bottles, the exploitation of those who pick ylang-ylang in the Comoros.”[2]« Derrière les flacons Dior, l’exploitation de celles qui cueillent les fleurs d’ylang aux Comores », from Florence Loève, is available on Médiapart website in French Prices are set by the buyers and are subject to many uncertain factors. Six euros a day for a picker, between 10 and 20 euros for a distillery worker… But locals don’t have much choice: They depend for the most part on these crops. “There is a contradiction in the luxury industry. Brands have a sustainable development stance, but to me, it is hardly credible, as the raw materials buyers have primarily financial targets,” the journalist points out to us. “And even if a brand tries to source its product with good intentions, the geopolitical situation of countries like the Comoros makes things very complex: The communication of brands must be more realistic about the subject.”

This is not an isolated case. Shamiso Mungwashu, a specialist in project development for Fairtrade Support Network Zimbabwe, thus reported the sum paid to farmers growing spices in his country at the October 2022 UEBT conference: 70 dollars a month for most of them, 170 dollars for the most qualified workers; the salary paid to pickers is even lower, and often, it isn’t controlled: less than 15 dollars a month for four to six months, in a country where it is the main source of income: “If you only consider meals, for a family of four people, you’re already over the minimum wage established by the law. And that’s without counting electricity, school.” He continued: “We are grateful to our partners. Because more of the communities I work with depend on you [the composition houses], on the relationship you have built, if only for the dignity of feeding their families.” He went on to raise a central question: “Paying 80 dollars is legal. But is it necessarily ethical?”

The competition of synthetics

In Madagascar, vanilla is a major resource, notes Georges Geeraerts, the president of the Group of Vanilla Exporters of Madagascar (GEVM) and the vice-president of the National Council for Vanilla: “The pod represents up to 8% of the GDP and provides income for over 150,000 local families. It’s a product that requires a lot of time and steps, and which should be considered as a genuine luxury. But its Fairtrade price has been calculated at 5.6 dollars per kilo; that is not sufficient at all to support a family, not to mention access to a decent education, for instance.” Collectors, preparators, packagers, storers, exporters and traders make up as many steps that hike up the price of the raw material for the composition houses that use it. There, the pod has a powerful foe: “Synthetic aromas, a thousand times less expensive, and whose fuzzy designation confuses consumers who don’t even know what it is they’re buying anymore.” The labels “natural flavor” and “natural vanilla flavor” don’t designate the same thing; the case is similar with fragrances: The quantity of raw material is not the same to obtain a vanilla extract or an infusion; yet this allows brands to lay claim to the presence of the ingredient in a composition in the same way. “This is what explains that we have been selling the same quantity of vanilla for the past 20 years, even though the population has increased, and that we have ended up selling it cheaper. Yet without the pod, synthetics wouldn’t exist: It is owed a tribute.” To mitigate this problem, a floor price was established in 2021 by the government of Madagascar, “but it was liberalized in 2023, with no transition period. It’s tragic, farmers can’t sell anymore, and end up doing it for ridiculously low prices so that they won’t lose their production.”

Price, the core issue of sustainability

The food industry is of course the largest consumer of the pod while proportionally, fragrance is a small buyer. But it has its role to play, especially since flavors and fragrances are created by the same company. Bear in mind that at a time when LVMH, headed by Bernard Arnault, is invading our boutiques with its many brands and reports an unprecedented turnover, Madagascar currently ranks 173rd out of 191 in the Human Development Index. The bonanza clearly hasn’t reached the farmers, yet without them, the great fragrances we love wouldn’t exist. “If you want to talk about sustainability and ethics, price, which remains a taboo in the industry, is the core issue. Situations vary a lot depending on countries and materials. Classically, prices are based on the time spent on-site or on the quantity harvested, but they’re quite unequal: For instance, the young work more quickly, older people are penalized, and this encourages child labor. In Guatemala, when the cardamom produced there is purchased at a decent price, which we calculate with the producers’ data, farmers can be paid enough to afford food, education for their children and a few leisure activities. But it’s a very volatile market,” notes Elisa Aragon, the co-founder and CEO of Nelixia, a company that produces raw materials in Latin America. For all that, the demand for naturals is high, even in household products. But client companies want to lower prices and seek out low-cost naturals. “The problem is that the very rigid hierarchies in purchasing companies, with the stockholders at the end of the chain, always try to drive prices down, without realizing the impact on those whose sole source of income this often is. Paying farmers better would change millions of lives, without having a really significant impact on the production cost of materials.” Global warming tends to amplify the problem: Yields are lower across the board; farmers must be supported in their transition to solutions such as agroecology, to enable them to become more resilient. “I think there isn’t a single raw material of which you can say that the price paid for it is fair. But more and more clients are asking us the question: Awareness is rising, and I am convinced things will start to change,” concludes Elisa Aragon.

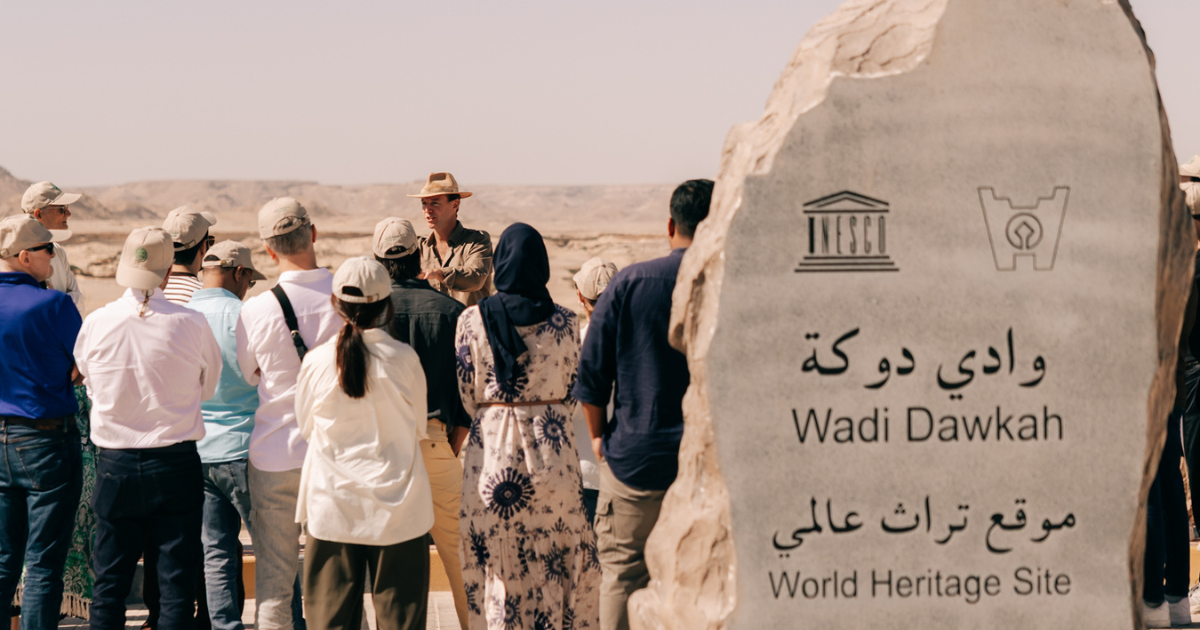

Supporting change

Nevertheless, a large number of composition houses are committed to helping producers become autonomous, by investing in equipment, for instance, setting up long-term partnerships, or creating instruments to assess the sustainability of raw materials and fragrance compositions… This is also one of the raisons d’être of the Union for Ethical BioTrade (UEBT), a non-profit organization created in 2007 to guarantee fair sourcing. Among the different evaluation criteria, “principle 3 concerns fair prices and the way in which companies must ensure that supply agreements with producers are based on dialogue, trust and long-term collaboration,” explains Rik Kutsch Lojenga, the executive director of UEBT. “Traditionally, compensation practices for harvesters and growers are informal, and the equivalent of the minimum wage is often not respected. We have created a progressive approach to assist companies: the valorization of the average time dedicated by producers to cultivation or harvesting at a minimum rate proportional to a living wage, supporting the diversification of local sources of income, or aiming to increase the salaries of contract workers. We also guide third-party auditors in determining living wages, which we define as the remuneration received for a standard week by a worker in a given place, sufficient to ensure a decent standard of living for them and their families,” he continues. To guarantee that purchasing companies respect the norms, UEBT carries out on-site verifications which enable it to define the basis for a progressive improvement that aims to support changes. It also offers a certification program for each ingredient, managed by a third-party organization, giving out a label for which it receives no compensation. But though such actions have improved the situation and globally raised the industry’s awareness, “the UEBT’s evaluations are not ‘guarantees’ and cannot single-handedly solve deeply rooted problems such as inequalities and power imbalances,” Rik Kutsch Lojenga points out. What’s more, audits have a price that the producer shouldn’t be the only one to bear, and supporting them financially in this matter should become a commitment for big brands, which benefit from the added value of these certified products.

Nothing in the bottle

Yet the situation remains precarious for workers and farmers, who are the first to bear the consequences of speculation or crises such as COVID-19 or wars… And of brands’ decisions. Natural raw materials are often showcased in the marketing campaigns of prestigious fragrances, along with their origins. Bulgarian roses, vanilla from Madagascar and ylang-ylang from the Comoros make us dream, and therefore, they sell. Nonetheless, we know that the cost of the concentrate is just a tiny proportion of the final price point of the bottle – between 1 and 5%, especially for widely advertised mainstream brands. But the true scandal, according to the perfumer Christophe Laudamiel, is their communication: “What is not widely known is that brands often use only 0.01 to 0.1% of a pure extract of a natural ingredient in their concentrate, just to be able to mention it in their communication. They cleverly let the public believe that these naturals make up a significant part of the fragrance, but if those formulas were to be made public, everyone would certainly be speechless.” He sent a letter to major groups in August 2022 in which he pointed out that 100 ppm (0.01%) of an ingredient in a composition shouldn’t allow brands to mention it in a press release. “For a 50-ml bottle, large groups pay between 70 cents and 1.50 dollars for the concentrate. This must cover everyone: the perfumer, the evaluator, the sales manager, legal fees and, certainly, farmers, cooperatives, transformers, transportation… Per kilo, of course, natural materials may be expensive, but if you put practically nothing of them in the bottle, you don’t guarantee anything to the farmer, who is paid based on volumes sold. Increasing their income would change little to the huge profits of these groups that own a bunch of licenses and that shamelessly congratulate themselves on their annual figures!” To shed light on this, the perfumer publishes on the Instagram account Fragrance Drama the analyses of certain famous fragrances. “It’s as though you pretended that a piece of clothing made of 99% nylon was a high-quality wool cloth. Luxury houses wouldn’t accept that for their fashion ranges. Why would they accept it in their bottles?” It is quite obvious that diluted efforts are no longer sufficient; awareness must be general if we are to envision a future that is different from the past. To echo the words of Sylvie Laurent: “Breaking the pernicious circle starts with dissipating illusions and legends.”

Notes

| ↑1 | You can watch “Child labour behind global brands’ best-selling perfumes” on the BBC Youtube channel, and read the article from Ahmed ElShamy and Natasha Cox on its website |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | « Derrière les flacons Dior, l’exploitation de celles qui cueillent les fleurs d’ylang aux Comores », from Florence Loève, is available on Médiapart website in French |

good article. minor correction — vetiver is endemic to india, not to haiti.