Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

This article was published in partnership with Symrise.

The history of the Maison Lautier 1795 illustrates the raw materials trade over the past two centuries. The house is currently being renewed by Symrise and is responsible for their full natural ingredients portfolio (Madagascar, Artisan and Supernature ranges). This invites us to re-examine Lautier’s legacy and continued influence on perfumery.

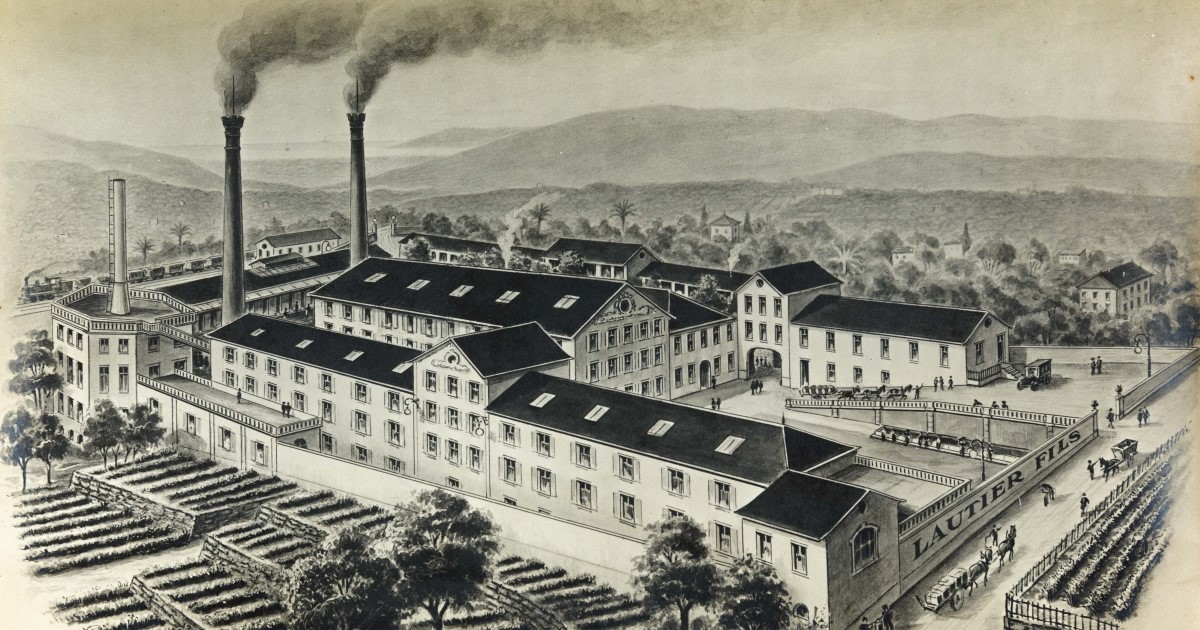

Among natural ingredient firms in Grasse, there were two giants: Chiris and Lautier. The companies battled for global supremacy in their trade throughout the early and mid 20th century, offering more and better materials to an ever-growing clientele. Eventually, they sought outside investment; Chiris was acquired by Universal Oil Products and Lautier, by Symrise.

Glover-perfumer

Ricardo Omori is senior vice president of fine fragrance at Symrise, and marvels at Lautier’s heritage. “When I arrived at Symrise, Lautier was a sleeping beauty.” The more he learnt about the company, the more fascinated he was by their archives. “They’ve remained intact despite all odds and are some of the largest on any old Grasse house. They’re practically an encyclopaedia on naturals.” Omori and his team proposed reviving Lautier as a supplier of premium natural ingredients for perfumery and flavours. “Lautier is a legend, a pioneer in so many domains. We realised we had to begin where they left off.” Symrise reopened Lautier for business in June 2022. They are currently building a state-of-the-art factory in Grasse.

Lautier’s origins date back to the mid 18th century, when François Rancé began as a glover-perfumer in Grasse. This history has been chronicled by Benoit Lanaspre, a descendent of Rancé and an authority on Lautier’s past. “A century later, the family business passed to two brothers-in-law, François-Alexandre Rancé and Jean-Baptiste Lautier. After a falling out, each partner went his separate way.” Lautier maintained ownership of the company and renamed it Lautier Fils.

Perfumer Max Gavarry was employed at Lautier from 1959 to 1966 before going on to co-create classics such as Z-14, Halston and Beautiful. He recalls tales of Jean-Baptiste Lautier’s beginnings: “Back then, the company sold natural ingredients to perfumers, soap-makers and druggists, as well as for food. They also offered finished fragrances and flavours for creams, tobaccos, powders, soaps, drinks, bonbons – all sorts of things.”

White lavender

Lautier’s first speciality to gain wide renown was Montblanc lavender oil. Perfumer Jacques Rebuffel, now a consultant at Robertet, worked at the firm from 1950 to 1995 and fondly remembers this ingredient. “It was distilled from plants growing wild near the village of Montblanc [in present-day Val-de-Chalvagne, northwest of Grasse].” There, Lautier negotiated contracts with landowners to secure lavender from the best high-altitude parcels. He also stipulated the harvesting method: only the flowers were to be picked, and not the stems and leaves as well, as was usually done. Each summer, he installed portable distillation stills on the slopes, so that the material was distilled fresh and at a high altitude, thereby lowering the boiling temperature and producing a lavender oil that was especially clean, fruity and floral. Reputedly, Caron purchased this ingredient for Pour un homme.

Today lavender has all but disappeared from Montblanc due to rising temperatures. Lautier is thus developing new sources thanks to information in their archives. Their current quality comes from Sault (near Avignon), where the firm began cultivating the plant in 1910. Catherine Dolisi, fine fragrance marketing director for Lautier and Symrise Europe, explains further: “This ‘white lavender’ is made from an old cultivar we revived, Lavandula angustifolia ‘Angèle’, whose flowers are very pale. It’s a Lautier exclusivity. The oil is floral, with a fruity shade of apricot.”

Apart from Montblanc lavender, Jean-Baptise Lautier sourced most of his ingredients near Grasse. This includes his eight ‘fundamental odours’, as he described them: cassie, jasmine, jonquil, orange flower, Parma violet, reseda, rose de mai and tuberose. His bitter almond oil was also particularly esteemed. What Lautier could not find in France, he imported: clove bud from Réunion, patchouli from Singapore, Damask rose from Turkey and sandalwood from Mysore, for example.

Co-distillation and tree mosses

In the 1870s, Lautier partnered with a citrus producer in Italy. Their bergamot oil was extracted by hand using a sea sponge, according to the ancestral method. “We found this old technique from Calabria fascinating and decided to try something similar with our mandarin in Madagascar,” says Dolisi. “The peels are gently expressed by hand, drop by drop. It’s a long and laborious process, but the oil is incredibly fresh and lively.”

Lautier took an interest in aromatic plants grown in Algeria. There he obtained a monopoly for an especially floral geranium oil – in fact, a co-distillation of geranium over rose – produced by monks at the Abbaye Notre-Dame de Staouëli. “Lautier felt that, with co-distillation, you could get a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts,” Dolisi clarifies. “We continue this practice, doing a co-distillation of Bourbon vetiver and bitter almond, for example. The result is an exciting encounter, at once woody and fruity.”

Jean-Baptiste Lautier sold to all manner of clients in the beauty, food and pharmaceutical trades, as revealed in his archives. “He was ready to talk with anyone: small customers, druggists who ordered some mint oil from Pégomas [near Grasse], or big Paris perfumers,” Lanaspre recounts. “He supplied Ed. Pinaud, L.T. Piver, Violet, Grossmith in London, and many others.”

Upon Jean-Baptiste Lautier’s death in 1877, his son-in-law, Joseph Morel, took over the company. He developed an interest in aromatic lichens, sourcing oakmoss in the forests near Saint-Auban, northwest of Grasse. Tree mosses soon joined the list of Lautier’s most important specialities. Ernest Beaux is rumoured to have used their oakmoss in his famous N° 5.

Water absolutes and upcylcing

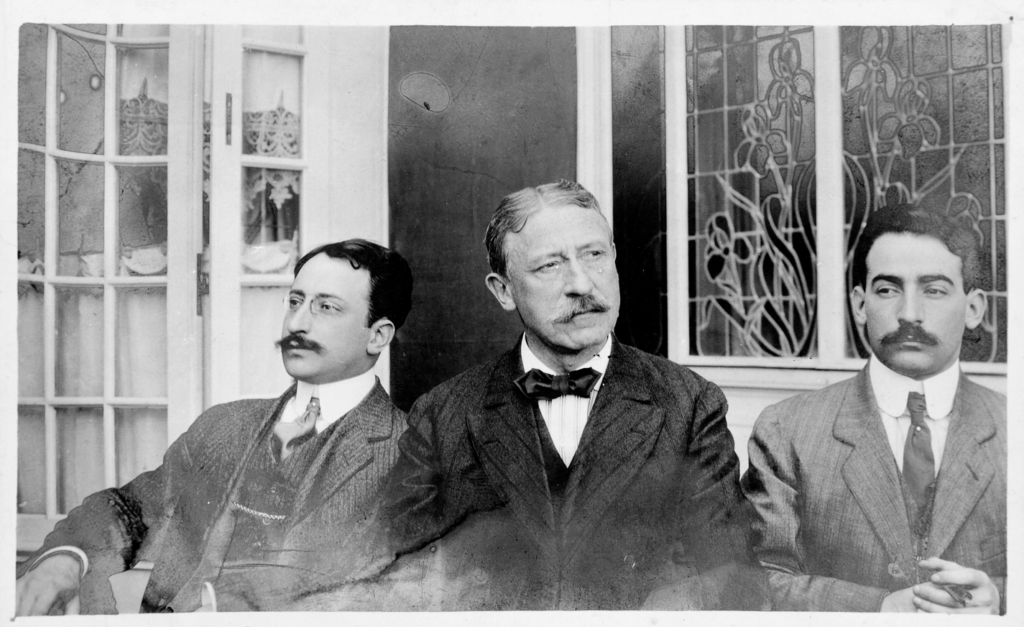

Joseph Morel was succeeded by his sons Alphonse, Paul and François, who encouraged new innovations at Lautier. The company’s technicians devised numerous extraction methods still used today. One example is volatile solvent extraction of distillation waters, creating absolutes to replace rose water and orange flower water, which were voluminous and prone to spoilage.

Lautier then applied this technique to many distillation waters previously wasted, such as those of geranium, lavandin and petitgrain. “It was upcycling before the term was coined,” Dolisi smiles. She explains how water absolutes influenced the company’s current technology SymTrap, used to extract vapour left over from the cooking of fruits or vegetables for jams, packaged soups and baby food. “Previously, these hydrolates were wasted, but their smell is very interesting. We capture the steam in an adsorber column and extract the odorous molecules. This has resulted in useful natural extracts of blackcurrant – more fruity and syrupy than the absolute – as well as banana, strawberry, apple, and others.”

Some of Lautier’s inventions were devised to maintain tradition. In the early 20th century, concretes and absolutes made by volatile solvent extraction began to replace the time-honoured practice of enfleurage. The Morel brothers felt the older method better suited to jasmine, jonquil and tuberose, though the manual labour involved made the extracts prohibitively expensive. “So Lautier Fils endeavoured to automatise the enfleurage process, taking out numerous patents as of 1913,” Benoit Lanaspre details. Eventually, these innovations succeeded in reducing labour by half, allowing Lautier to offer high-quality absolutes from pomade at much lower prices than those of their competitors. The company abandoned enfleurage in the 1970s but is now attempting to revive the practice using vegetal fats.

Several of the firm’s finest materials came from surprising locations. One such ingredient was cistus labdanum from the Esterel mountains (near Cannes). Gavarry tells the story of its discovery: “A forest ranger would come home every evening smelling terrible, his trousers stained with a dark, sticky resin. His wife told him, ‘You smell too strong. You should show this gum to the perfumers.’” The ranger’s son-in-law was Alphonse Morel, whose chemists identified the resin as Cistus ladanifer, previously unknown in France. “He told the ranger, ‘Don’t tell a soul. We’re going to harvest the branches and keep their origin a secret.’” The French labdanum was far better than the normal Spanish quality. Lautier marketed it as Beirut labdanum to mislead their competitors, some of whom even dispatched scouts to Lebanon. The secret was successfully maintained for three years.

From Madagascar to the Hôtel Carlton

Lautier was among the first to invest in perfumery materials from Madagascar. “The Morel family recognised very early on the country’s potential for ingredients,” Ricardo Omori states. “Lautier’s first purchases there date from 1928, for clove bud and ylang.” The latter product was distilled on Nosy Be by Father Clément Raimbault, who established ylang-ylang and vanilla plantations to support local leper colonies. “Today, Lautier is one of only a few perfume companies in Madagascar with control of the entire local supply chain. We have our own factory, team and artisans on site.”

Father Raimbault features alongside countless other characters in Lautier’s archives. Lanaspre mentions more examples: “We have correspondence with perfumers, some of whom maintained a warm relationship with Lautier Fils for decades: Ernest Daltroff at Caron, Robert Bienaimé at Houbigant.” Also present are clients such as Dior, Lanvin, L’Oréal, Patou and Yardley. “Elizabeth Arden, as well. They transferred production of the perfume Blue Grass to Lautier Fils, starting a long association between the two companies.”

Occasionally, the Morel brothers received clients wanting to buy directly from the factory rather than Lautier’s Paris office. For example, “Henri Robert [of Bourjois-Chanel] often bought in Grasse, and was very fond of some of Lautier’s products,” Max Gavarry recalls. When an important perfumer came to visit, “they were very well received. They were great men, and their business interests in Grasse were considerable.”

Rebuffel elaborates on the pomp and circumstance of these occasions. “In general, we’d receive the perfumers at the luxurious Hôtel Carlton in Cannes. Then they’d head up to Grasse to smell our raw materials. Paul Vacher would visit. Jean-Paul Guerlain came all the time, buying floral absolutes, labdanum. He really put us through the wringer, by the way!”

A trade network worthy of an empire

Lautier’s clientele was international. The company operated factories in France, England, Lebanon, the United States and Japan, with sixty sales agents around the globe. “Already in the 1950s, Lautier was pursuing business in emerging markets such as Mexico, Brazil and China, countries that are now key for us,” remarks Omori, who is himself Brazilian. To satisfy demand, Lautier maintained a product offering of over a thousand natural ingredients sourced from sixty different countries, a trade network worthy of an empire.

The firm is remembered both for its raw materials and the many luminaries nurtured within its walls. From the 1960s to eighties, young perfumers such as Carlos Benaïm, Jean Martel and Christopher Sheldrake worked there. Jean-Claude Ellena served as perfumer from 1976 to 1986. During the period, Christian Rémy managed raw materials purchasing for the company, before helping his wife Monique found the Laboratoire Monique Rémy (later acquired by International Flavors & Fragrances).

In the mid 1990s, Lautier merged with the storied German firm Haarmann & Reimer, which became Symrise in 2003. The house now embodies Symrise’s focus on natural ingredients, furthering their commitment to sustainable development.

Omori concedes that Lautier’s legacy is humbling. “It’s an enormous technical and cultural inheritance, all in our hands.” He is determined that Lautier achieve a bright future based on its history of tradition, innovation and respect. “We’ve assembled a great team and are hard at work on the next big thing. And that, conversely, is where the archives come in.” He returns to his first remark, adding, “I really believe, if you know who you are, you’ll know where to go.” For Symrise, that place is Grasse.

—

Will Inrig

Will Inrig is a perfumer and researcher in perfumery history. His creations include Homesick. (Observer Collection), Acide (Éditions M.R) and the duo Coquet and Vaudou (Alexx And Anton). He is the author of Poems About Sex and co-author of several Nez + LMR naturals notebooks.

Comments