Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

This article was published in partnership with IFF.

Although perfumers at IFF have long been accustomed to working together, the company went a step further by making the collaborative approach official in the early 21st century. An approach that has since been adopted by all the composition houses. Behind the scenes of a revolution.

The perfumer’s universe has always been shrouded in a veil of secrecy, keeping alive the myth of the creator working alone. And it is true that solo composition was a reality last century, when relationships between perfumers were very different. “Whenever I showed my formulas to my mentor, Bernard Chant, he’d give me ideas for taking them forward, but it definitely wasn’t a two-person process!” remembers Carlos Benaïm, master perfumer at IFF. “Back then all the formulas were kept in a large safe: a room full of formulas on paper!” And while perfume creators did occasionally collaborate, “there was always a senior perfumer in the spotlight who played the prima donna role,” he explains. One person managed to change all that: “Nicolas Mirzayantz [prevously Divisional Chief Executive Officer for IFF Scent] truly believed that a different system was possible: there was a good atmosphere between perfumers and Nicolas succeeded in channelling that positivity, which was unique in our industry then,” says Carlos Benaïm. After that, perfumers could create with one or more of their colleagues. “I remember the first time Sophia Grojsman and I both put our initials to the same formula,” he says. It was the dawn of a new era for IFF, which has since notched up plenty of success stories using this model, including La vie est belle for Lancôme, Invictus and Phantom for Paco Rabanne, Libre for Yves Saint Laurent and, more recently, Luna Rossa Ocean for Prada.

From the first spark to putting together a team

The creative team is not formed until after the first exploratory stage, when perfumers have the chance to work on their own concepts: “the initial idea is the fruit of intuition, a thought, a goal, something that is forged individually,” explains Jean-Christophe Hérault, senior perfumer at IFF. The ideas generated in this first stage are soon put to the test with the creation process, which puts composition houses in competition. The perfumers’ different concepts are proposed to brands and gradually eliminated as the projects progress, narrowing down the choices until a handful of notes make the final cut. Building teams is an organic process that takes place during the development phase, and the perfumer whose note is selected can then suggest that other colleagues join the adventure: “When the request comes from the perfumers themselves, it boosts their motivation. Because this sort of work needs the team to be really solid and every member to be capable of putting their ego on the side,” says Carlos Benaïm. The group also expands to reflect different needs: a perfumer might have a technical question on a note’s diffusion. Or want to incorporate a colleague’s specific accord. Which is how Carlos Benaïm joined the team behind the creation of Libre for Yves Saint Laurent. Anne Flipo wanted to come up with a “feminine fougère”. Her idea was to break away from the codes of the traditional accord and take a “Saint Laurent-style” approach to it. After all, the couturier had taken the traditional men’s suit and turned it into a suit for women! “I’m very attached to orange blossom because of my Moroccan roots,” explains Carlos Benaïm. “I had an accord that Anne smelled and really liked: it was a lovely way of making her fougère more feminine.”

A second brain

Calling on perfumers also depends on how far down the line the project is. New people are brought onboard tactically, based on the tasks at hand: “we don’t do the same things at the beginning and the end of the project,” reveals Juliette Karagueuzoglou, senior perfumer at IFF. “At the beginning, the idea is raw, it needs to be smoothed out; we have to think about the archetypes of formulas we can graft it onto. While at the end of the project, we’re looking at how we can tackle the test phase.” The benefits of co-creation are not simply creative and technical, there is also a psychological dimension: “Composition is like running a marathon as well as riding a rollercoaster!” explains the perfumer. “When things are really hectic, you might need a colleague for their knowledge of the client, or simply to boost working capacity. Sometimes the client changes direction, feels under pressure. It’s important to have a second opinion to help make the right decisions, particularly in difficult moments.” The rush of adrenalin and the importance of collaboration remind the perfumer of the sensations she used to experience playing volleyball: “In a team, not everyone is good at everything, each person has to focus on their own task. It’s fairly easy for me to get up and running because I’m used to following a coach’s strategy. You have to exploit each team member’s strengths: there’s the one who’s better at reading the game, the one who hits really hard, the one who knows how to get the ball into just the right spot.”

Embracing differences

Two-person composition is an excellent source of learning: “You get to know each person’s personal vision, viewpoints you hadn’t thought of, new combinations of ingredients, it’s really instructive,” says Jean-Christophe Hérault. For instance, he enjoyed discovering Carlos Benaïm’s cultural references when they worked together on Spice Bomb Infrared for Viktor & Rolf: “Carlos has travelled a lot, in Morocco, France and the USA, so he offers in-depth knowledge of the American market.” And as it turns out, collaboration is equally “enriching with more experienced perfumers and their younger colleagues.” Different creators have different ways of thinking, classifying, designing. “It’s this effort we have to make to adjust to differences that helps us stand back from the formula.”

Pascal Gaurin, a VP perfumer at IFF New York, also enjoys the collaborative aspect of composing, which he compares to what is currently happening in the music industry: “The industry is inspiring because it’s highly collaborative, famous singers aren’t afraid to cooperate with other artists: you see Thom Yorke from Radiohead working with REM, for example, or with the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Teaming up with another artist introduces a different way of working. If you get three perfumers together to compose a tuberose, they’ll come up with three different arrangements. In perfumery, just like in music, you always want to be surrounded by the best creators.”

From one generation to the next

The mentoring trainees receive from senior colleagues is certainly the first collaboration perfumers experience in their career. A relationship that gives novices the chance to show their formulas and discuss their aesthetic choices: “Pierre Bourdon was also very strict,” recalls Jean-Christophe Hérault. “Once there were more than thirty lines in a formula, you had to justify the choice of different ingredients and classify them according to how long they took to evaporate so the formula would be easy to understand. A really exhilarating feeling of complicity came out of our discussions, I was hungry for his advice.” The perfumer has now become a mentor himself, guiding a trainee and providing her with exercises “which she wouldn’t do at school”: choosing a daily smell and analysing it. For example, the odour of basil: “she succeeded in synthesizing it with only seven ingredients! I learn a lot as well.”

While young perfumers just out of perfumery school may be brimming with creative ideas, they do not always have the technical skills needed to meet a request. Collaboration between different generations means they can benefit from the experience of their older colleagues, whose familiarity with clients means they can quickly remodel a formula. “Puig, L’Oréal, Yves Rocher: each company has its own outlook. A mod [new trial from the first formula] is produced in a different way for each of them,” explains Juliette Karagueuzoglou. “This detailed client knowledge takes time to build up. That’s also what I try to pass on to my trainees.”

An extensive taskforce

Centre stage: a perfumer, then two perfumers, then three and sometimes four. But in the shadows an entire team is hard at work to make sure the project is won. Members include the evaluators: “They are professionals with a perfect understanding of the market, the client and the competition. They’re familiar with the ingredients but they don’t have access to the formulas. They provide us with general comments using the same language as the client,” notes Carlos Benaïm. “The interpretation of the comments has to come from the perfumer.” The team also comprises salespeople: “they are just as involved with the creation as perfumers and evaluators,” points out Juliette Karagueuzoglou. “It’s easy to come to an agreement because there’s a dialogue going on: our real intelligence lies in knowing how to listen so we can understand the client’s problem. We’re not making perfumes on our own behalf, but on behalf of the brand.” Working collaboratively requires plenty of skills. Carlos Benaïm feels that the most important of them is “respect for the original idea. For instance, when I used to go on holiday, I’d entrust my work to Joséphine Catapano. She would give it back to me very respectfully, reporting on everything that had happened: I apply the same philosophy myself.” As Juliette Karagueuzoglou sees it, availability is a decisive factor because a project takes up a lot of time for both the perfumer and their assistant. “In fact, when you join a team, taking part in the first rounds isn’t always very effective. You have to be resilient,” she says modestly. “A perfumer sometimes steps back. How can the impact of a mod be measured? It’s impossible to say who has contributed the most to the project’s progress.”

New tools

With the development of video conferences between two sites, shared computer tools and connected scales, the 21st century has ushered in a new era of modernity for perfume creation, speeding up the options for collaboration. The advent of artificial intelligence and data access marks the next stage in the process: “Here again perfumery has experienced the same sort of relationship with technology as the music industry: people used to be reluctant to use computer-assisted creation, whereas now it’s common practice,” notes Pascal Gaurin. Access to artificial intelligence makes it possible for perfumers working in different markets and centres to collaborate. Paco Rabanne’s Phantom is an example of a fragrance designed on two continents: the brief for the perfumers was “What is the future of Paco Rabanne?” Loc Dong, who came up with the first accord, travelled from France to New York. He then entrusted Juliette Karagueuzoglou with the task of taking the accord further: “Loc wanted to work on a traditional ingredient: a creamy lavender he sliced through with styrallyl acetate [a rhubarb note] to modernise it. The accord was pretty out there. We spent six months together working on it to make it acceptable on certain markets.” Then the project speeded up, with meetings happening twice a week rather than once every two weeks. Anne Flipo and Dominique Ropion joined them to bolster the team. Incorporating AI meant they could work out what certain facets could deliver to consumers: “The tests we did on neuronal activations helped us push claims centring on well-being, self-confidence and sexiness,” reveals the perfumer.

Offering as it does additional resources, time and ideas, teamwork has become the norm for all major launches, with solo creation confined to follow-on versions and niche brands. And even when the creative process is a solo affair, would it not be “influenced by other perfumers?” asks Jean-Christophe Hérault: “All creators draw on the past, on the works they have encountered during their career. Look at how the artistic dialogues between Picasso and Braque transcended them.”

The tie that binds perfumes shows that composition, whether a solo or team activity, is ultimately always a form of co-creation.

- This article was published in partnership with IFF.

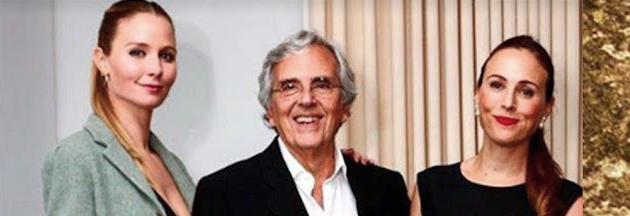

Main picture: Anne Flipo and Nicolas Beaulieu, who worked together to create Good Fortune for Viktor & Rolf ©IFF

Comments