Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Stars, supporting actors, director, producer, scriptwriter, technical team, distributor, financial partners: when it comes to films, it would be unthinkable for the director to be the only one mentioned in the end credits and for the names of everyone who contributed to the release of a movie to be left out. In the perfume industry, although the creative chain is also made up of many links, each contributing to the project at their own level, nothing similar exists today. While perfumers are increasingly in the limelight, the other contributors continue to remain anonymous. Why is this? Could this anonymity change now that certain voices in the industry are calling for more transparency and education?

For a long time, perfumes were associated purely with the name on the bottle: N°5 with Chanel, Opium with Yves Saint-Laurent and Angel with Thierry Mugler. There was a conscious choice to let the public attribute the creation to the couturiers who founded the houses. And those same couturiers either maintained an artistic vagueness on the matter or simply took credit for the compositions launched under their name, as Clément Paradis recently pointed out. From the 1980s onwards, new houses such as L’Artisan parfumeur – founded by Jean Laporte – and Serge Lutens allowed figures other than those from the fashion industry to step centre stage and embody their fragrances, even if they weren’t always the only ones involved in creating them. As for the perfumers? Unknown to most people. They were rarely mentioned in the press until the 1990s – with a few exceptions, such as Germaine Cellier, the socialite creator of Balmain’s Vent vert and Piguet’s Fracas, described as “the best nose in France” in 7 jours news magazine in 1944.

The perfumer-author

In 2000, Frédéric Malle was the first to systematically include on the bottles of the perfumes he launched the names of those who composed them, and who were considered by his house as their authors. In the 2000s, and even more so in the decade that followed, perfumers became an integral part of fragrance messaging and were increasingly placed in the spotlight. It is now rare for a launch not to mention, or even highlight, their name. Does this mean that a link in the chain is at least getting well-deserved recognition? Not always. While collective creations have become the norm for large-scale projects, is everyone really being given the credit their contribution merits? A brand or composition house may sometimes choose to highlight women, an illustrious perfumer or, on the contrary, a novice, for reasons of internal policy or to best fit the chosen messaging, regardless of the reality of the creative team.

There are also a few notable examples that run counter to this emphasis on perfumers: Hedi Slimane at Celine and Tom Ford for his own brand remain faithful to the tradition (and fiction) of the couturier-perfumer, keeping hidden the people who formulated their memories or concepts. Their example, however, underlines the importance of the creative director, who guides and approves the perfumers’ work while also contributing to the creative process. In a fashion house, the creative director must infuse the fragrances with the couture spirit, like Alessandro Michele at Gucci, head of fashion from 2015 to 2022; he worked with Alberto Morillas to imprint the romantic and baroque brand on the house’s perfumes, from Bloom to Mémoire d’une odeur. This delicate task is often delegated to external teams due to a lack of time.

Essences and molecules

But a fragrance is not only the work of perfumers and creative directors. It is of course composed of raw materials, which have to be produced. Brands boast proudly of the presence of natural ingredients, often flanked by their country or region of origin: vanilla from Madagascar, bergamot from Calabria, and so on. The work of the farmers, the pickers, the people involved in transport and the raw material companies that transform the flowers, leaves, pods and bark into perfume ingredients is rarely mentioned, as Dominique Roques underlines in his book. Similarly, before entering the palette, molecules are the result of long and costly years of research by chemists – or more rarely of unexpected discoveries. We would have no Calone without John J. Beereboom, Donald P. Cameron and Charles R. Stephens of Pfizer (some spiteful tongues will no doubt feel that the world would be no worse off), no Hedione without Edouard Demole (Firmenich), no ethyl maltol without Bryce Tate, Robert Allingham and Charles R. Stephens (Pfizer again). And therefore probably no Angel either. Would Olivier Cresp’s tests have been successful without this synthetic compound reminiscent of cotton candy, used for the first time in such large quantities in fine perfumery? The identity and success of a perfume can sometimes (also) be down to a molecule, and thus to the research of the chemists who made it available.

The long development process

Before a perfume can hope for success, it has to undergo a lengthy development process at a composition house. Apart from the rare cases of in-house perfumers (Guerlain, Chanel, Cartier, Hermès, Caron, Dior, Vuitton, etc.), brands generally delegate the development of fragrances, through a licence, to a multinational (Coty, Puig, L’Oréal, etc.) which then turns to a company employing perfumers (IFF, Givaudan, Robertet, etc.) to bring their creation to life. “The development process lasts from several months to several years, when the composition house is like a beehive. Evaluation, marketing, consumer research, laboratories, R&D, regulations: there’s lots of hard work all centring on the perfumer, while the salesperson acts as a conductor,” explains Audrey Barbéra, Global Fine Fragrance Category Leader at Firmenich.[1]October 2021 interview for the Spanish edition of The Big Book of Perfume. Responsible for a client account (L’Oréal, Interparfums, etc.), the salesperson receives the brief outlining the creative intention and specifications for a future launch and acts as an interface between the client and the other participants throughout the process: this is therefore the person who ensures that the project runs smoothly right up to delivery of the concentrate if the project is successful.

For the olfactory side of things, the evaluator (usually a woman) works hand in hand with the perfumer(s). Evaluators are also in charge of an account and several brands (Armani, Saint Laurent, Prada, or Mugler at L’Oréal; Gucci, Marc Jacobs, Calvin Klein at Coty, etc.) or a region (Middle East, Asia, etc.), and are rarely mentioned despite the fact they make a significant contribution to the creative process. “We really play the role of co-pilots alongside the perfumer, which implies a great deal of trust between us,” emphasises Cynthia Salem, evaluator at Mane. They have a deep understanding of the brand universes they work for and what their expectations are as well as all the perfumers’ collections, made up of the formulas they have already created for their different projects. The evaluator helps perfumers come up with an olfactory translation of the brief and find creative avenues, smells each new trial with them, inspires them and gives them fresh motivation if necessary, and in the end decides which concepts will be submitted to the client to win the project. “One of the challenges of development is not to lose the initial note, which is sometimes smoothed out by trying to please as many people as possible,” adds Cynthia Salem.

The marketing team also contributes to the process. At the beginning of a project, they research what constitutes the brand’s DNA and the raw materials that could meet the brief in order to inspire the perfumers. They are then asked to present the mods in the most effective way possible, with illustrated presentations explaining the perfumer’s creative intent.

Consumer testing

To maximise the chances of winning important projects, another composition house department comes into play: the consumer insight team, which conducts consumer tests. Over the past twenty years, consumer testing has become increasingly important: more projects are being tested, and more and more tests are being conducted as development progresses. “In the early 2000s, testing was used to validate a note,” says Samuel Willer, Fine Fragrance Consumer Insight Director at IFF. “Today, our work is divided into two parts. On the one hand, we regularly conduct online studies not related to any specific project to get an understanding of the public’s conscious and unconscious expectations on subjects such as well-being, sustainable development and gender fluidity, which we feed into the teams. On the other hand, as part of a project, we organise tests with research institutes to give consumers trials to smell.” They smell blind, without knowing anything about the brand or the concept, and have to answer simple questions: “Do you like this perfume or not? Is it powerful? Feminine? Fruity? Fresh?” Can the tests lead to a radical change of olfactory direction for a project? Not really, according to Samuel Willer: “We generally start with a very strong and distinctive creative idea, which is like a diamond in the rough that we gradually hone until it becomes a lovely gemstone.” The challenge is also to take into account the public’s perception, which may differ from what the perfumer wishes to express. This department, with the strategy, choices and advice it offers, therefore has a decisive role to play in a perfume’s future success.

At the heart of the labs

In parallel to this development work, different laboratories are busy every day, working hard to implement the perfume. Firstly, the perfumers’ assistants (or laboratory assistants) weigh the different formulas which will then be evaluated by the teams: an extremely painstaking, precise and repetitive task which requires great rigour to avoid any error that could be detrimental to the smooth running of the project. Then there is the sampling laboratory, which prepares a sometimes astronomical quantity of small bottles that will be sent for testing or to the customer. Finally, a technical laboratory carries out stability tests on the various mods. The brief specifies the liquid’s final colour, which is part of a fragrance’s identity – would Angel (decidedly a textbook case) be Angel without its blue hue? – but can be affected by certain ingredients or interactions between them. And if the project is successful, the composition house guarantees that the perfume bottles will not change smell or colour when stored at room temperature, usually for 30 months. “We screen each formula to identify and resolve any stability issues. It is often the natural ones that give us a hard time,” says Nadine Gherdaoui, Fine Fragrance Technical Project Leader at Symrise. Pepper, ylang-ylang and ginger can give the perfume a cloudy appearance; some citrus fruits that are very colourful at the start fade over time. A liquid can also change colour during its ageing process due to reactions between certain materials: a blue-tinted perfume that turns yellow over time would thus become green. “We can opt to use different qualities of raw materials or adjust the quantity of some of them as a last resort, as this can have an impact on the perfume’s olfactory identity. That means we have to work with the creative teams to find the best compromise between identity, stability and the desired shade,” continues Nadine Gherdaoui. To check the fragrance’s stability over time, accelerated ageing is simulated by exposing it to natural light or UV lamps as well as to heat, when it is left in an oven for varying lengths of time. The laboratory can then suggest the use of possible stabilisers to ensure optimal preservation of the fragrance. This is a crucial role: a project can be lost because of unresolved technical problems, even if the perfume started off as the favourite, because the client will turn to a second choice.

While the composition house refines its proposals, the brand that will launch the fragrance is working on the concept, name, bottle, packaging and messaging up until the launch. Factors which, if they are coherent and correspond to the zeitgeist, can determine a perfume’s success and reputation beyond its olfactory profile. Behind the image of the solitary perfumer sniffing blotters in their office and having a light-bulb moment are a multitude of people working in the shadows, occasionally for several companies, each with a precise and sometimes decisive role, and who put in many months or even years of effort to produce a perfume. In the same way as the various participants in a film, which is never attributed to the director alone, perhaps all these people whose work leads to the birth of a perfume will one day be more visible, valued and recognised by the public. When will we see the appearance of perfume credits, just like the ones on cinema screens, which could be accessed by scanning a QR code on the bottle, for example, or simply on brand websites? As we see a host of perfume-related digital technology initiatives being rolled out, this could be a possibility in the near future – provided of course that it would be welcomed.

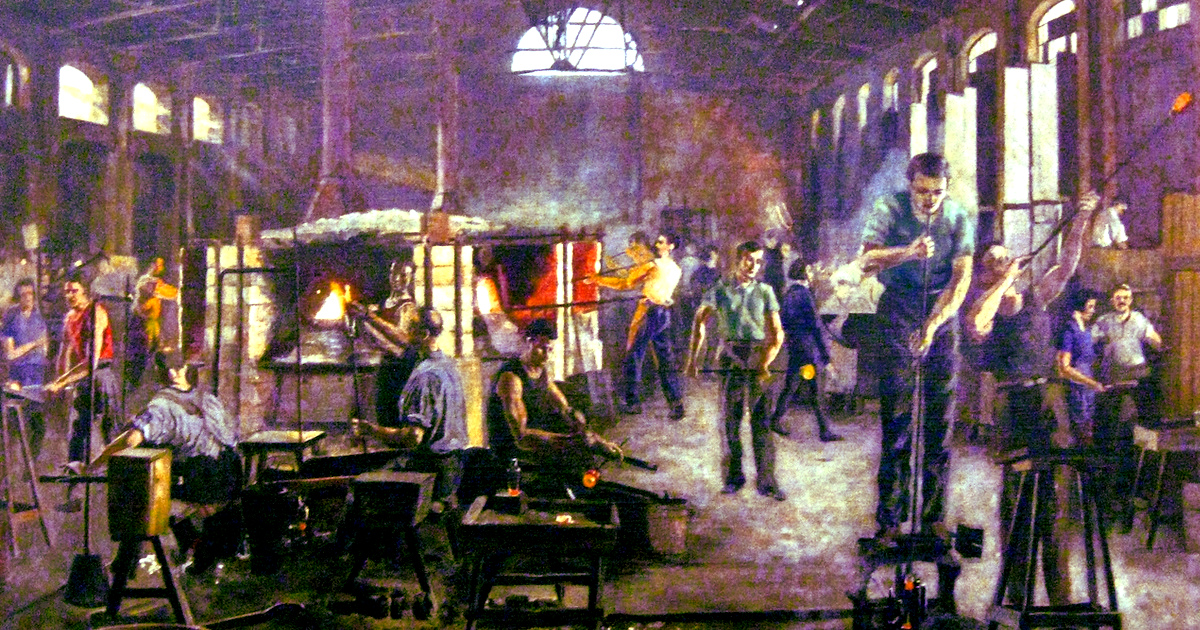

Main image: Robert Maillard, La Halle de la verrerie de Portieux, 1935. Source: https://leverreetlecristal.wordpress.com/

___

REPORT « REINVENTING PERFUMERY DISCOURSE »

- Reinventing perfume discourse, introduction

- Olfactory dissonance, between discourse and reality

- Interview of Christophe Laudamiel: “50% of perfumery is plagiarism or remixes, it’s time to adopt a code of ethics”

- The press kit, the art of staging the immaterial

Notes

| ↑1 | October 2021 interview for the Spanish edition of The Big Book of Perfume. |

|---|

Comments