Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Our day-to-day lives are being increasingly infiltrated by what is given the catchall name of artificial intelligence. Perfumers are no exception. So how does AI change our relationship with the creative process? Drawing on an historical analysis of his profession, Jean-Claude Ellena offers a review of these new technologies, often championed by the perfumery industry.

This title is based on the maxim “man is an adventure”[1]See, for example, Paul Valéry, Cours de poétique [Lesson in Poetics], Gallimard, 2023 that poet and philosopher Paul Valéry was fond of quoting to emphasise the uncertain nature of all our destinies. I like the saying because it contains a promise and is applicable to everyone. I can certainly apply it to perfume since each new creation is an adventure for me: its destiny, its future success, is uncertain and impossible to predict. Personal experience has led me to the conclusion that olfactory composition is the result of a thought process with endless aesthetic implications, and not the result of a programme, as the industry would like it to be. I have only rarely encountered the success suggested by tests. The mistake is to want to turn perfume into a science, i.e. “[a] series of recipes that always work”,[2]Paul Valéry, Tel Quel [As It Is], Gallimard, 1941 to again quote Paul Valéry. Which would of course be reassuring for decision-makers – or accountants, who make the decisions these days.

A new syntax

In the 19th century, all the arts, music, choreography, painting, sculpture and literature, found different ways, reflecting their different natures, to embrace the constraints of certain obligatory forms of expression which had to be learned, just like we learn language syntax. Then in the 20th century, as our industry freed itself from the exclusive use of natural extracts and adopted the addition of synthetic molecules, a new syntax emerged and the art of perfume was born. It may come as a surprise, but natural extracts were aromatic compressions of plants: jasmine smelt of jasmine, rose of rose, and orange blossom of orange blossom; they were complete, finished olfactory works, and the compositions formulated by talented “florist” perfumers were called “bouquets” or named after flowers. Although these names were undoubtedly poetic, they were also accurate and tangible. They did not designate “fragrances” as such – a term that nowadays conveys an idea, a dream, deeply imbued with the power of suggestion. With the advent of chemistry, the status of perfumers shifted from artisan to artist: someone who no longer worked on a commissioned object, but who came up with a creation based on personal inspiration.

Artisans or artists, to understand ourselves and understand the world, we all need interpretive frameworks. Philosophers, poets, writers, musicians, painters, sculptors, actors, cooks and perfumers are people who take on the task of putting us in touch with who we are, of making us more mindful of others and the world around us. That’s what novelists do with their words, painters with their colours, musicians with their sounds, cooks with their dishes, perfumers with their fragrances. But before representing the world, their world, they have to decipher it. The perfumer’s framework is made up of odours: they are the perfumer’s words, colours and sounds. To take one example, phenethyl alcohol smells to me of wilted roses. But that’s not all: its floral facets can also suggest jasmine, lilac, lily of the valley, peony and narcissus while also evoking some types of alcohol, such as saké, and cooked rice. I would also describe the odour as soft, bland and full. Whereas a rose extract only smells of rose, with specific features that depend on where it’s from. I have on occasion introduced visitors, customers, to natural extracts. What usually happens, strange as it seems, is that people couldn’t recognise the raw material. Why? Essentially because of the aromatic complexity of the extracts, the excess of component details which makes them hard to grasp. An accord made up of three synthetic products (a caricature), on the other hand, can produce the requested odour and create a sense of astonishment. This doesn’t mean that we can do without naturals, but rather that we need to use them to add a dose of mystery.

The new perfumery tools

The 1970s were pivotal in terms of technological progress, for fragrances as well as in a great many forms of artistic expression. This is the decade when the industry really began to look at research into the sense of smell. The appearance of a new analytic tool, chromatography, was at that point only of interest to the novice we then were. Not all perfumers understood the benefits it offered us. It was the machine that selected the most astute and trained a new generation of creators. We finally had access to formulas for the archetypes of perfumery, which until then had been kept secret. Specifically, chromatography produced an “X-ray” of them, corresponding to their structure. We knew that a creation was made up of a multitude of products. The tool only told us about the molecules belonging to naturals and pure synthetics. Which was a lot of information – but not enough. The result told us nothing about the essential complements that forge a fragrance’s soul, its style. The machines were incapable of analysing the thoughts that guide the perfumer, as artificial intelligence does – a point I will discuss in more detail below.

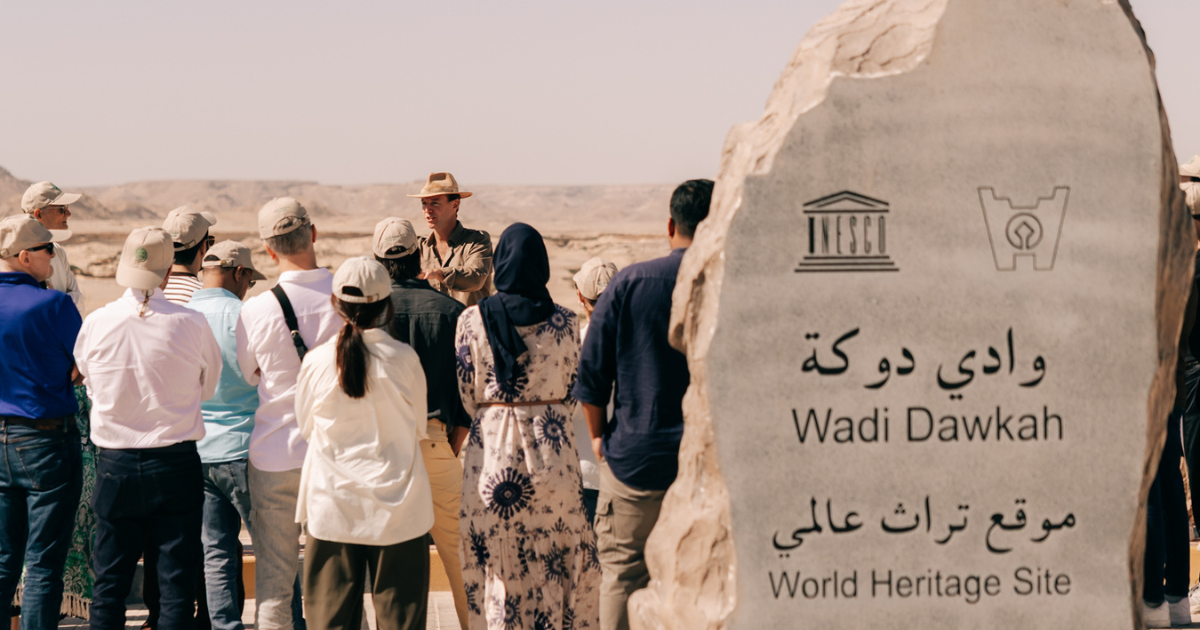

This was the same era when the industry developed techniques to capture odours in the same way we capture sounds, but using a different method: headspace, a tool linked to chromatography used to analyse the most volatile molecules released by flowers, fruit, wood and even the skin – without having to resort to the artisanal technique used by Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, the famous murderer in Patrick Süskind’s novel. It generated so much excitement that scientists and perfumers were dispatched to explore the world of treetop aromas on the canopy raft.[3]The “canopy raft” is the name given to scientific expeditions on a mission to explore the canopy of tropical forests. The tool was credited with the ability to produce a miracle that proved to be out of its reach: capturing the living smell of flowers to reproduce them. For the headspace technician, essences obtained via extraction or distillation were made with gathered flowers – so-called dead flowers, which makes no sense since odours are still alive and continue to evolve after the plants are picked. Over time, the tool fell into disuse and a few years later a new profession emerged: raw materials sourcer, in great demand in perfumery schools. It consists of roaming the planet and sniffing out new sources of aromas to ensure they are grown sustainably, ethically and in ways that respect people and places. Nevertheless, headspace did teach me that in the olfactory composition of flowers or other plants, the relationships between odours was more important than the proportions of the constituents. For example, a jasmine flower does not smell exactly the same in the morning, at midday and in the evening, regardless of the percentages of the components, which vary as much as fivefold or even disappear. Proving that, while technical innovations broaden our horizons, they usually do so where they are least expected.

Another factor in how perfumes evolved was the rise of air travel and the development of tourism, which opened the door to new tastes, new smells and new methods. The dawn of the nouvelle cuisine movement was the result of leading French chefs journeying eastwards, particularly to Japan. People have always been more adventurous when it comes to taste rather than smell. This trend went on to influence perfumery, not simply through the use of new odours such as exotic fruits and spices, but also in how it was approached, its form and style, making space for the pared back, for simplicity, itself another form of virtuosity. The emergence of the new science of marketing shifted the luxury industry from a supply-centred model to a commercial model governed by customer demand: concentrations in fragrances would triple, but costs fell as a result. This led perfumes to gain in performance and stability but to lose 50% of their value, carried over into advertising budgets.

The noughties saw an upheaval I found troubling, with the release of “single-odour” creations based on a single molecule, such as Ambroxan or Iso E Super, diluted in alcohol. This for me was the death of perfume, the death of creative thinking, as it was reduced to simply an odour, a word with no backstory.

Creativity in the face of artificial intelligence

With the rise of AI, yet another technical innovation that is being applied to perfumery, I worry that creativity will be sapped. Commercial demands very often focus on diffusion, staying power, performance, quantifiable data, things that can be fed into a computer to invent tomorrow’s perfumes. There is every chance that exactly the same questions will be asked, “hey, can you make me – the friendly tone is a vital part of making machines appear human – a new scent based on the three latest worldwide successes, but with a little touch of something I can’t quite put my finger on, because we still need a dash of imagination,” in a process similar to that way that ChatGPT makes it possible to create texts word by word. For perfumes this would be odorant by odorant, in such a way as to ensure that each of them would be followed by the statistically dominant occurrences in the mega database used by all the fragrance companies. Which would compromise all future research, i.e. creation. I am reminded of something Christian Bobin said that resonates for me: “there is no artificial intelligence. The root of intelligence, its invisible centre from which everything shines, is love. We have never seen and we will never see artificial love.”[4] Christian Bobin, La Nuit du cœur [Night of the Heart], Folio Gallimard, Paris 2018, p. 88. And if we did, it would no longer be called “love”, merely the product of morose delectation.

Creative production stems from disorder not from order or statistics, it relies on the unexpected not the expected, and tends to arise from what we do not know. And in the world of perfumes, the sole limit is reproductions in the market, olfactory mimicry. My heart goes out to perfumery juniors tasked with finishing off the machine’s work. To young creators, I say: learning doesn’t only come from books, nor simply from copying or reading formulas; you learn by doing, by working every day, year in year out. Nothing beats trial and error for building up knowledge. This is the price to pay if you want difference, distinction and creativity. You will have understood that the codes and canons of today are those of the market, of marketing. The economy decides. But creation does not have the same meaning for the artist as it does for the consumer. For the artist, it lies in the act of doing, something that might take three days or ten years, whereas for the consumer it’s all about the final product, in this case perfume. I know perfectly well that the history of art shows us that artists created what they were commissioned to make. However, I doubt that Pope Sixtus IV took a marketing approach when he gave a brief for painting the Sistine Chapel. He simply summoned the finest artists of the age.

At the risk of surprising you, it’s not the perfume at the end of the process that interests me, important though it is. What I find fascinating is the journey, the trail, the endless questioning of myself I will embark upon to create it. The added value of the creative process lies in the time taken to work and reflect, the act itself, the shaping, the questioning, the journey, the paths I explore. And despite all this, once I decide my work is at an end, I have no way of being sure I could pick it up again without refining or ruining what I achieved. Every work demands a conscious act, and I believe that perfumers do not have the capability to achieve precisely what they are seeking; they cleave as closely as possible to their desire. For the perfumer, the core question is: what exactly do I want? As a composer of fragrances the temptation to endlessly revise my work does exist, even for creations already on the market. Practicing an art is a lesson in humility and not a functional, conclusive, utilitarian and efficient demonstration. Creating is a lesson in love, it is about giving, giving of yourself. When I do what I do, I express myself, I make discoveries, I gain knowledge, I receive. And the more I receive, the more I give.

Jean-Claude Ellena, March 2023

Main visual: © Romain Bassenne

Notes

| ↑1 | See, for example, Paul Valéry, Cours de poétique [Lesson in Poetics], Gallimard, 2023 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul Valéry, Tel Quel [As It Is], Gallimard, 1941 |

| ↑3 | The “canopy raft” is the name given to scientific expeditions on a mission to explore the canopy of tropical forests. |

| ↑4 | Christian Bobin, La Nuit du cœur [Night of the Heart], Folio Gallimard, Paris 2018, p. 88. |

Comments