Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

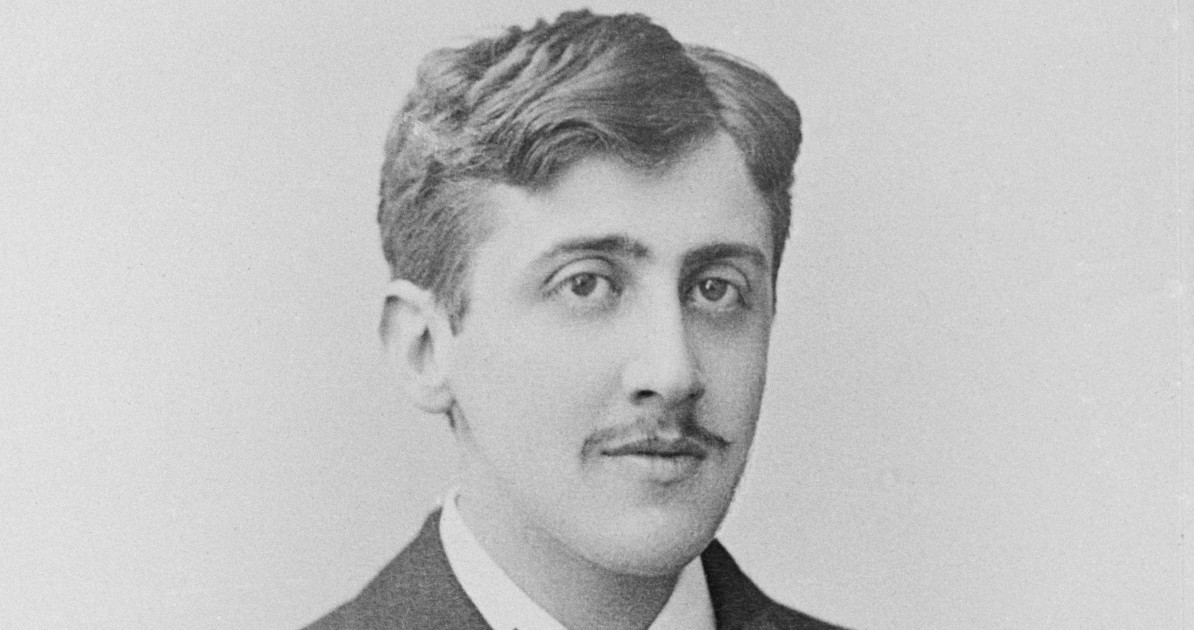

In his saga, the asthmatic writer portrays a hypersensitive narrator whose nose is just as fine as his palate. On the occasion of the centenary of his death this November 18, 2022, we offer you an article by Clément Paradis, originally published in Nez, The Olfactory Magazine – #13 – Near or far.

Ah, “the taste of the piece of madeleine soaked in [a] decoction of lime-blossom”! What a blockbuster! The expression is even used to describe the effect a fragrance can have on us over time. True, there is indeed something breathtaking about seeing “the whole of Combray” condensed in a cup of tea, like Marcel Proust does at the beginning of In Search of Lost Time, published in seven volumes from 1913 to 1927 – the village of his childhood captured in a fleeting, overwhelming reminiscence. Though Proust was assuredly a man “of taste”, his less-celebrated exploration of the olfactory world is just as delicate and full of insights on art and life.

Born in 1897, Marcel Proust was diagnosed with asthma at the age of 9; as he was coming back from a walk in the Bois de Boulogne, the child suffocated so badly that he almost died. From then on, his sensory world would develop as a complex labyrinth. He avoided the heady perfumes of his time, which he couldn’t stand, while immersing himself in nineteenth-century literature, which celebrated the most intoxicating scents. His novel bears a trace of his delights; in it, he quotes the description of “[a] delicate and subtle odour of heliotrope […] exhaled by a cluster of scarlet runners in flower” as “one of the two or three most beautiful passages” of Chateaubriand’s Memoirs From Beyond the Grave. He also recalls Baudelaire’s verve and the way the poet sought, “in the odour of a woman, of her hair and of her breast, those inspiring analogies which evoke for him ‘l’azur du ciel immense et rond’ and ‘un port rempli de flammes et de mâts.’” Smells make space legible and open up the horizon of new correspondences for the reader.

Unfamiliar, dreaded aromas

The hero of In Search of Lost Time, a nameless creature constantly traversed by the world and its words, ceaselessly re-evaluates his position within the olfactory dimension of the world. In his childhood home, his grandparents’ house, it all starts with the staircase that separates him from his mother, a foe that “gave out a smell of varnish which had to some extent absorbed, made definite and fixed the special quality of sorrow that I felt each evening”. But his early years also bring their share of friendly smells: The first “perfume” mentioned in the novel is that of the chamber pot after eating asparagus. The child’s mind animates them and imagines “they played (lyrical and coarse in their jesting as the fairies in Shakespeare’s Dream) at transforming my humble chamber pot into a bower of aromatic perfume.” The bedroom becomes a womb: In the novel, the hero visits many, in family homes or hotels; he recalls them through their exhalations.

With Proust, perfume isn’t always where we’d expect it, and his wariness as an asthma sufferer may have led the writer to become more keenly aware of any change in the air. As he develops his olfactory culture, the hero makes us understand that unfamiliar, dreaded aromas are also those that enlighten us. One of them journeys through the course of the novel: vetiver.

As he discovers the room he has been given at the Grand Hôtel de Balbec, a seaside resort to which Parisian society moves for the season, the protagonist finds himself “from the first instant […] morally intoxicated by the unfamiliar scent of vetiver”. Is it given off by the overly scented soaps of the establishment? The effluvia of In Search of Lost Time reveal their full power in this scene from the second volume, In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower. They are more than fleeting annoyances; the offensive they launch leaves the narrator bereft: “Having no world, no room, no body now that was not menaced by the enemies thronging round me, invaded to the very bones by fever, I was utterly alone; I longed to die.” What was meant as a restful holiday turns into a nightmare. A few hundred pages later, as the season draws to an end, the character, a valued customer, is offered better rooms for his next stays: “I had now become attached to mine, into which I went without ever noticing the scent of vetiver.” The room has been adopted, and he will repeatedly stay there. Indifference even turns into more intense feelings and more incongruous associations: By the end of the novel, the hero discovers that he is “thrilled” by the aromas, “unpleasing” in themselves, of naphthalene and vetiver, which bring back “the blue purity of the sea on the day of my arrival at Balbec”. The Haitian root merges with the landscapes of the coast of Normandy, reminding us that our olfactory relationship with the world is arbitrarily woven. In Proust’s novel, smells therefore determine relationships with space and its remembrance, as well as social choreography. But few characters wear perfume: La Berma, the great actress inspired by Réjane and Sarah Bernhardt, is one of them; or rather, we learn in passing that she uses “oceans of perfume for her dogs”. The main figure whose scented trail we can follow is – unsurprisingly – Odette, the “cocotte” who becomes Madame Swann. Her favourite fragrance can be smelled “even onto the staircase” and turns her dwelling into “a mysterious chapel” of many pleasures, “in the heart of which there [was] so much warmth, so many scents and flowers”. As these suspicious pleasures don’t thrill Françoise, the hero’s housemaid, she tries to discredit Albertine, the woman who shares his life for a time, saying she will turn the place into a perfume shop.

Cattleyas and syringas

But what repels some attracts others: Swann, the charming and cultured socialite, is sometimes guided by his sense of smell in the splendour of Parisian receptions. We see him take the hand of a marquise and plunge “an attentive, serious, absorbed, almost anxious gaze into the depths of her corsage, and his nostrils, intoxicated by the woman’s perfume, [quiver] like a butterfly ready to go and settle on the half-glimpsed flower.” As Swann’s manners are faultless, things go no further. But with Odette, when he realises the attraction that he feels for her is reciprocated, another ballet is performed in the intimacy of a carriage. The cocotte holds a bunch of cattleyas and wears more of the same flowers in her hair and “in the cleft of her low-necked bodice”. As the horse starts, they are thrown forward from their seats, the cattleyas start falling out, and Swann offers to tuck in those that adorn Odette’s cleavage. “I really had to fasten the flowers; they would have fallen out if I hadn’t,” he shyly explains to the young woman, who doesn’t resist. The scent of the flowers, or rather, their possible lack of scent, becomes the pretext found by Swann to get even closer: “Seriously, I’m not annoying you, am I? And if I just sniff them to see whether they’ve really lost all their scent? I don’t believe I’ve ever smelt any before; may I? Tell the truth, now.”

In the intoxication of floral exhalations, their paths merge when others diverge. While Swann happily “does a cattleya”, the novel’s hero will later suffer, as he is the victim of a wily deception on the “evening of the branch of syringa”. He’s gone home happy: Madame de Guermantes has given him, because she knows he is fond of them, syringas from the south of France. Only, as he climbs the stairs, he runs into Andrée, a friend of Albertine’s, who “seems to be distressed by the powerful fragrance of the flowers”. She tells him that Albertine, as she dislikes strong scents, “won’t be particularly pleased to see those syringas”. When he enters the apartment, he isn’t surprised to see her flee and take refuge in her room. He will learn after his companion’s death what really happened that evening: The two young women’s repulsion was feigned, possibly meant to keep him from seeing the unmade bed and other traces of the erotic games they may have indulged in. Thus, smells weave complex social games, scenes that mark the narrator, to such an extent that he comes up with a strange theory: Our minds operate in the same way a perfumer works.

A synaesthete hero

The protagonist is a creature of desires, and his experience of the world converts his disappointments into insights and replaces fantasies with real knowledge. But how can this reality best be rendered tangible? His admiration for an eminent aristocrat, the Princess of Parma, leads to an elaborate theoretical explanation: “For years now, like a perfumer adding fragrance to a solid block of fat, I had been drenching this name, Princess of Parma, with the scent of thousands of violets.” Here, he describes the process of enfleurage, that is, the capacity of fats to naturally absorb the scent of plants. But the flowers have been replaced by our fantasies, absorbed by the people who surround us. However, the dream is always fleeting and a source of disillusionment: By spending time with the Princess of Parma, the hero realises she is just a woman like others he has known, human, humble. His mind must therefore undertake a second operation: This consists in “expelling, by means of fresh chemical additives, all the essential oil of violets and all the Stendhalian perfume from her name, and replacing them with the image of a little dark lady, bent on good works”. Scents and images blend for the synaesthete hero who constantly recomposes the smells he associates with each person.

Proust was not only attentive to olfactory sensations: He was also interested in the manufacturing process of fragrances after reading Le Pays des aromates by Robert de Montesquiou (which he considered as a compendium of the history of perfumery), and of the Orphic Hymns, prayers to the gods of ancient Greece that were preceded by the mention of the aromatic substances to be burned while they were recited. The author thus teaches us that incense was the perfume of the sea, but also of the goddesses Dikè, Themis, Mnemosyne, the nine Muses and Circe. He is disconcerted by the fact that many divinities shared the same scent but draws yet another lesson from it: The inner scents and desires we project onto the people who inspire us are less personal than we think.

This explains why disappointments and the sadness that follows are also, over the course of our lives, so similar. But these fits of pessimism are fleeting in the novel: Life always manages to dispel the narrator’s dark thoughts by surrounding him with sensations to decipher, emanating from the most diverse spaces, such as the Parisian madeleine or the hawthorns of Combray. Mischievously, Proust chooses a humbler reference to complete his reasoning: the perfume vessel, the synthesis of what is most trivial and most crucial, the infinitesimally small and the infinitely large – for “an hour is not just an hour, it is a vessel full of perfumes, sounds, plans and atmospheres.”

- This article was originally published in Nez, The Olfactory Magazine – #13 – Near or far.

Main visual: Portrait of Marcel Proust by Paul Nadar, 1892 (detail) ©Ministère de la Culture – Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Paul Nadar

Comments