Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

What’s to be done with Oriental fragrances? For a few months now, the perfume world has been reflecting and taking a stand on the use of the adjective “Oriental,” which can be perceived as potentially offensive to certain populations. It is therefore time to take stock of what we smell and dream through this contested term, first by studying its uses and its olfactory meaning, then by digging into its scope in a colonial context. The first stage of our research will therefore address the olfactory and semantic issues at the origin of this family of perfumes, in order to better understand the ambiguities of its history.

The spring of 2021 saw an unprecedented shake-up in the Anglo-Saxon perfumery industry: Many critics and institutions announced they would stop using the descriptor “Oriental,” well known in our latitudes.

In the United States, The Fragrance Foundation, among the first, wanted in May 2021 to remove from its vocabulary this term considered “outdated and offensive.” [1]Jessica Matlin, “Why Are We Still Describing Perfumes as Oriental?”, Harper’s Bazaar, May 26, 2021, online: … Continue reading Australian historian Michael Edwards, who consulted laboratories, perfumers, brands and bloggers, spoke of the growing feeling in the perfume industry that the term “oriental” is “outdated and derogatory.” [2] “The ‘Oriental’ category is being replaced by ‘Ambery’ on the fragrance wheel”, Trendaroma.com, June 28, 2021, online: … Continue reading A similar reflection was made in June by the American Mark Behnke [3]Mark Behnke, “Improving the Perfume Vocabulary for the Right Reasons”, colognoisseur.com, June 23, 2021, online: https://colognoisseur.com/improving-the-perfume-vocabulary-for-the-right-reasons/ … Continue reading on his blog Colognoisseur, while in August the Council of the British Society of Perfumers published a statement in the same vein: The term is considered Eurocentric, outdated and derogatory.[4] Kira Haslett, “BSP to Replace Fragrance Descriptor ‘Oriental’ With ‘Amber’”, Perfumer & Flavorist, August 9, 2021, online: … Continue reading

The outrage continued into late December: On the website Ça fleure bon, editor Michelyn Camen took up the subject in an article summarizing the year 2021, stating that “oriental […] is not a term to describe the way a perfume smells. It is outdated, insulting and not acceptable. Ambery, resinous, vanillic are some alternatives.” Her text calls for a thorough renewal of our vocabulary, wishing “by 2022 not to see the term on any website or used as a fragrance description,”[5]Michelyn Carmen & Ermano Picco, “Best Fragrances of 2021 (Ermano and Michelyn) + A Very Good Year Draw”, Ça Fleure Bon, December 26, 2021, online: … Continue reading while allowing Ermano Picco to describe a new fragrance, a few lines above, in a disturbing way, as a “smooth oriental with myrrh, fruity notes and a sparkling bergamot opening.” The Fragrance Foundation is also the source of some contradictory statements, as the French wing of the institution continues to use the term that is incriminated in the United States in its communication. [6] “Les 7 familles de parfums”, The Fragrance Foundation France, online: https://www.fragrancefoundation.fr/education/les-7-familles-de-parfum/ (accessed on 03/01/2022). The vocabulary thus presents itself in its resistance, in the constant and unconscious use we make of it when dealing with perfumery.

It is true that the American and French situations need to be distinguished. The initiatives of the Anglo-Saxon perfume industry are part of a broader movement, supported by Barack Obama himself when he passed a law in 2016 banning the use of the term “Oriental” to describe people of Asian origin in government documents. [7] Madison Park, “U.S. government to stop using these words to refer to minorities”, CNN.com, May 22, 2016, online: … Continue reading In France, home of the Nez editorial board, on the other hand, these considerations may seem a little remote: The usage decried by the Obama administration has been out of circulation for much longer. The French vocabulary now clearly disconnects the qualification of the origin of Asian people and the “oriental” aesthetics of objects such as perfume. In the same way, in France, the Orient more spontaneously designates a cardinal point, the East, which is not the case for the Anglo-Saxons who speak of the “Middle East” when French-speaking people speak of the “Moyen-Orient” or study at the INALCO, the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations.

It is therefore necessary to be particularly careful when importing and exporting an apparently simple word from one culture to another, even more as many discussions on fragrances use and abuse the term “oriental” to the point where we no longer know what is included under the descriptor. Are we talking about scents, “oriental” accords? About the origin of the raw materials? About the origin of perfumes, such as the expensive “ouds” prized in the Emirates but provided by another “Orient,” Southeast Asia, where the precious wood is produced? Or, more prosaically, are we talking about visuality, a design, such as the countless bottles adorned with black and gold, destined for the “oriental market”?

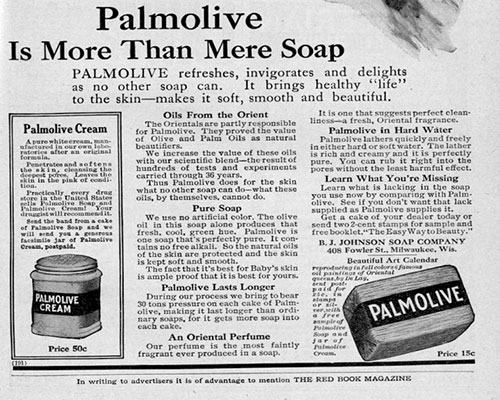

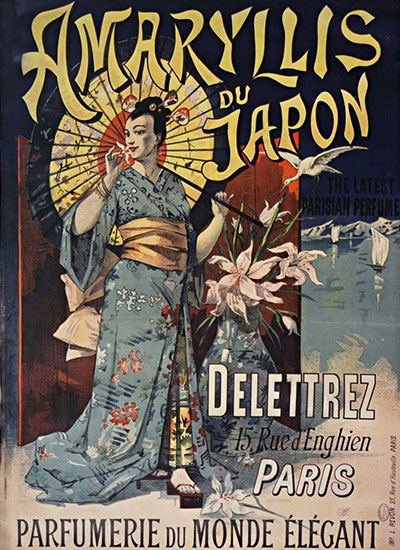

Here lies the eternal problem of technical vocabulary: When a word is used to say everything, it ends up meaning nothing. However, the use of the term “oriental” to refer to perfume has, in the past, designated more precise phenomena. In the mid-19th century, one could already read in Le Charivari the praises of the “rouge au carmin de Chine that Guerlain can boldly put next to the best products of oriental perfumery.”[8]Charles Philipon, Le Charivari, May 29, 1854. French perfumery was not yet concerned by the term: It was a matter of designating products from distant lands. It was not until the beginning of the 20th century that the brands themselves adopted the term in their advertising, especially those aimed at the American public. Guerlain’s Mitsouko was presented in magazines as the perfume that captured “all the romance and lure of the Orient” as early as 1922. [9]Advertising for Guerlain, Town & Country, Vol. 79, N° 3853, New York, USA, December 1, 1922, p. 19. Even before that, Palmolive soap announced its “oriental perfume”[10] Advertising for Palmolive soap, Red Book Magazine, Vol. 18, N° 2, New York, USA, December 1911, p. 417. in 1911. Internal communication is gradually updated: When Firmenich presented its new Exaltolide molecule to French perfumers in 1934, it is finally described as perfect “for woody or ambery notes or for oriental or fantasy notes.” [11]Revue des marques de la parfumerie et de la savonnerie, August 1939, 17th year, n° 8, not paginated.

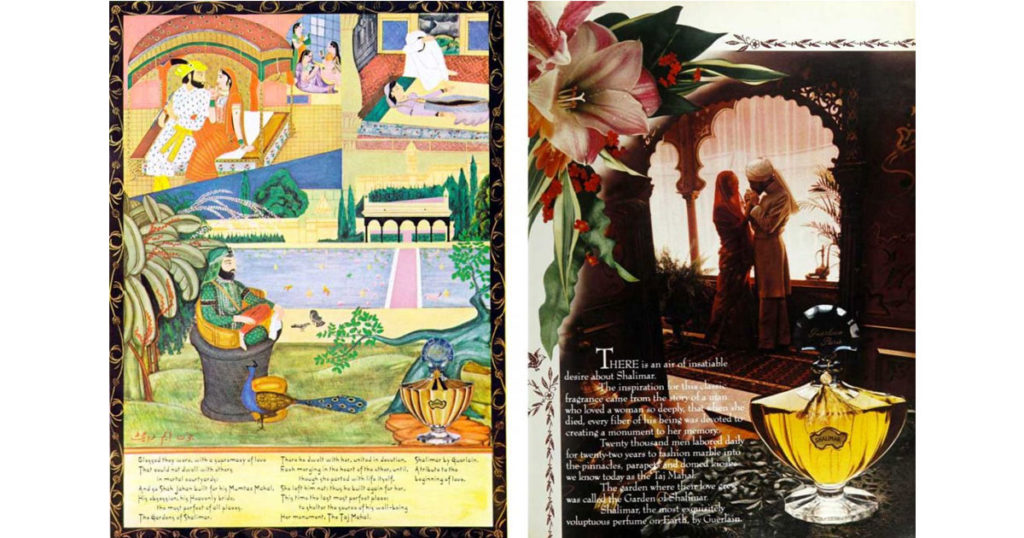

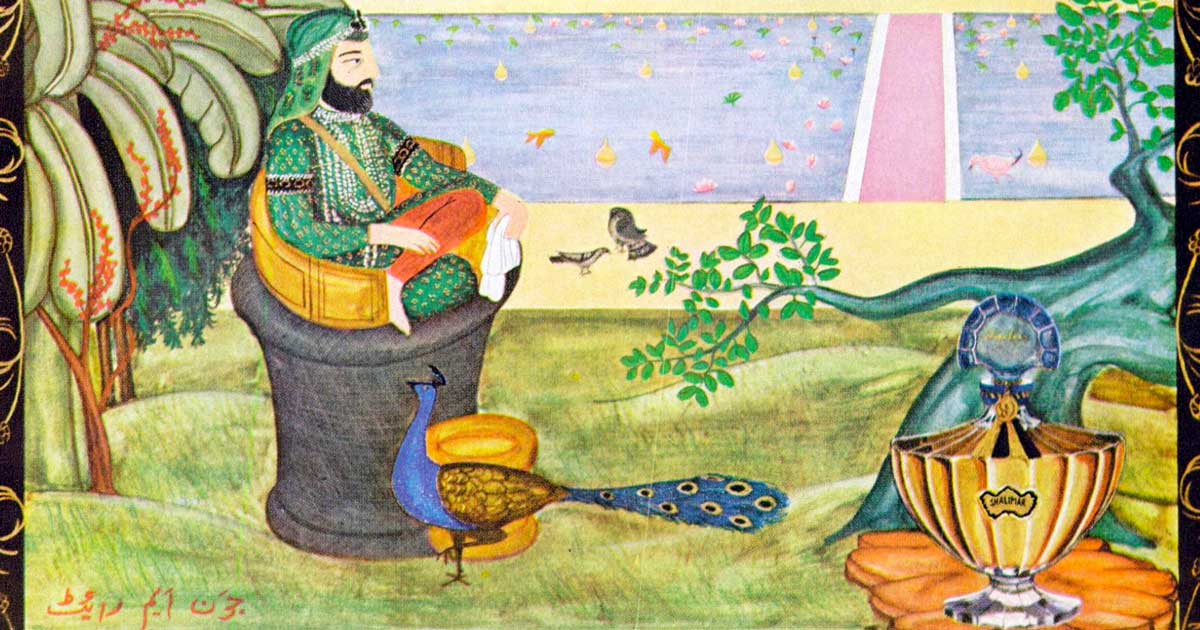

A part of French perfumery thus progressively became “oriental,” drawing on an exotic imagination that gave birth to Guerlain’s Shalimar in 1925, but also to Opium by Yves Saint Laurent in 1977 and Poison by Christian Dior in 1985. Although these perfumes brought the oriental family back into fashion in the 1980s, the category is now decried. The olfactory compositions themselves are not criticized, but what is hidden behind the term “oriental” is disturbing, irritating and sometimes frightening. The following article will therefore try to understand why this olfactory family is nowadays laconically presented as “pejorative” or “derogatory.” Can we rethink the classification of fragrances? Should perfumery be reinvented in light of the new controversies?

Right : Advertisement for Guerlain’s Shalimar, Seventeen, New York, USA, Vol. 38, N° 9, September 1979.

In order to answer these questions, two detours will be necessary: The first one goes through the theory of the classification of perfumes, the second through the study of Orientalism. Our first work will therefore be to distinguish between the analysis of discourses on perfume and the study of scents themselves, while seeking inspiration from perfume specialists – because this is perhaps where we should start: What do the theorists who use the term “oriental” say?

Family names

If the perfumer Edmond Roudnitska (1905-1996) is above all known for his Eau d’Hermès (1951), Diorissimo (1956) or Eau sauvage (1966), he was also one of the great theoreticians of perfume aesthetics, author of the classic Le Parfum in 1980. In this book he proposed a “practical classification of perfumes” which is composed of “some main groups: Floral, Chypre, Ambery, Tobacco, Woody, Aldehydic, Spicy, Fruity, Leathery, Green, Fresh, with all the combinations of these groups with each other.”[12] Edmond Roudnitska, Le Parfum, Paris, PUF, 1980, p. 11. But in Roudnitska’s seminal writings, there is no trace of the term “Oriental” being used as an olfactory family or descriptor for a scent.

Far from being marginal, his work is rather followed by the rest of the community: the Société Française des Parfumeurs (SFP)[13]“Les familles olfactives”, Société française des parfumeurs, online: https://www.parfumeurs-createurs.org/fr/filiere-parfum/les-familles-olfactives-102 (accessed on 03/01/2022). has been using a similar vocabulary since 1984, still classifying different fragrances into seven families: citrus, floral, fougère, chypre, woody, leather and amber-oriental. The old denomination used by the industry during the 20th century finds here a small place, without being able to satisfy the SFP, and for good reason: On the level of logic, of the “classificatory reason,”[14]This question of epistemology is addressed by Patrick Tort in La Raison classificatoire, Paris, Aubier, 1989. A more specific approach to the classification of odors is proposed by Joël Candau & … Continue reading the term does not follow the tendency proposed by this list. Indeed, if one can distinguish two approaches to the classification of perfumes, one “olfactory” and the other “metaphorical,” it is indeed the olfactory approach that has been chosen by the SFP.

Perfume, between olfaction and metaphors

The classification of smells, like many other things, is the subject of endless debate. Two tendencies nevertheless emerge: Either we can classify them according to an olfactory profile, by focusing our attention on what happens in the “juice” and on the arrangement of raw materials (using the terms of the linguist Roman Jakobson, we can speak then of classification according to a “metonymic”[15]We draw here on the seminal work of Roman Jakobson in “Deux aspects du langage et deux types d’aphasie”” (1956), Essais de linguistique générale, trad. N. Ruwet, Paris, Éditions de … Continue reading scheme), or we can classify smells according to what the perfume evokes, by taking into account the fantasy that it conveys, a kind of poetic metaphor (Roman Jakobson speaks of a “metaphorical” scheme). It is easy to understand that perfumers, fine connoisseurs of the raw materials, tend toward the first method, while amateurs, for whom perfumes are indissociable from the promotional and critical discourses that surround them, may have more affinities with the second.

The advantage of the “olfactory” classification is its scientificalness: It allows to reason by contiguity. The perfumes of the same family are brought together by their olfactory arrangement alone: All the citrus fragrances are structured around materials extracted from citrus fruits (or imitating them); all the florals have a flower or a floral bouquet as their main theme; and so on. The second method of classification is poetic: It takes into account the perceived meaning of the perfumes, their “metaphorical meaning,” which allows them to be grouped into families where the discourse on femininity, masculinity or even the Orient takes precedence. It is no more about taking “scientifically” into account the composition of perfumes, since it is perfectly possible to signify “femininity” and “the Orient” with ambery or floral or woody materials, this analogical dimension of perfume being always linked to a given culture. The citrusy smell of verbena or lemon, on the other hand, does not radically vary from Japan to Madagascar: A smell remains a smell, but what it evokes is subject to infinite variations.

Memories of Chypre

The experience of classification shows us, however, that these two methods are not impermeably walled. Reasoning with the pure categories described above confronts us with certain limits that are also found in the SFP classification because beyond the “orientals,” two categories still seem strange: the chypres and the fougères.

Their names are strangely similar to those of the classes we have described as “poetic.” The other families mentioned by the SFP refer to raw materials (such as floral extracts), but these refer to an “elder perfume” with a founding accord: Coty’s Chypre in 1917 and its accord of oakmoss, cistus-labdanum, patchouli, bergamot; and Houbigant’s Fougère royale in 1882 and its accord of lavender, oakmoss, coumarin, bergamot and geranium. If in some ways it is still about recalling scents, an ambiguity is introduced here: It is no longer a question of reproducing by imitation of raw materials, but of culturally constructed accords, which have known a more restricted circulation in time and space, these “chypres” and “fougères” being specific to modern Western perfumery.

Initially they were smells, not metaphors, but these smells gradually became pure ideas: Who really remembers the original accords? Certainly not non-Westerners who have never smelled these perfumes. As for us, how many of us, even among perfumers, have experienced the original Chypre or Fougère royale to verify that a classification is correct? It is likely that today we live much more with the idea of these perfumes, of their place in the olfactory landscape, than with their founding accords. It is as if the initial olfactory analysis of Fougère royale and Chypre had gradually solidified into a purely metaphorical approach. It is clear: There is necessarily a “metaphorical” element in olfaction, just as there is an element of olfactory analysis in all metaphorical classifications. [16]Patrick Tort, La Raison classificatoire, op. cit., p. 12.

Caught in amber

If no olfactory profile is spontaneously assimilated to the “Orient,” it should also be noted that this olfactory family does not take its name from a founding perfume either. The term “ambery,” on the other hand, appears to be a more appropriate name for three reasons: Firstly, ambergris has been a key material in perfumery for thousands of years; secondly, this material inspired Georges de Laire to create the base “Ambre 83,” a complex mixture of synthetic vanillin and natural ingredients such as labdanum, vetiver, patchouli and synthetic musks, which is used in numerous scents; and finally, there is a founding perfume of the “ambery” line, Ambre antique by François Coty, launched in 1908, which, as its name indicates, draws on an imaginary time different than that of the “Orient.”

It is probably with this history in mind that Jean-Claude Ellena, following Edmond Roudnitska in his discourses on the aesthetics of perfume, also puts forward the ambery scents in his book Perfume: The Alchemy of Scent. [17]Jean-Claude Ellena, Perfume: The Alchemy of Scent, translated by John Crisp, New York, Arcade Publishing, 2011. He recalls that the word “amber” refers to a base, a combination of a few substances, to the accord present “in amber perfumes that are sometimes called orientals.” The perfumer takes the time to explain his choice of vocabulary, evoking his mistrust of categories that imprison us in “stereotyped mythical aromas of the Orient as seen through Western eyes.”[18]Jean-Claude Ellena, Perfume: The Alchemy of Scent, op. cit. & Jean-Claude Ellena, Le Parfum, Paris, PUF, 2007, p. 53. Without naming it, this clarification appears as a nod to a book by the American academic Edward Said published in 1978: Orientalism[19]Edward Said, Orientalism [1978], London, Penguin Books, 2003., a reference text on the question of the dreamed Orient which, without dealing directly with perfume, still resonates with a disturbing relevance today.

The debate could end here for those who are only concerned with the classification of scents, as the notion of “amber” seems to be both satisfactory and long-established: Its metaphorical charge is sufficiently weak to allow serious reflection on the structure of European perfumery. But it already reveals a situated look at the olfactory question: What does “amber” mean for the history of Mexican, Egyptian or Kanak perfumery, and even for us who have neither known Ambre antique nor the original smell of the “Ambre 83” base? In order to widen the spectrum of perfumes that we can distinguish, embrace, understand, because they come from elsewhere, it is necessary to rethink the current classifications, including those that seem the most “politically correct.” This cannot be done without welcoming the actors of other horizons, the perfumers foreign to the Western olfactory culture, the continuators of perfume traditions we perhaps have never heard of. In order to understand the determinations of the metaphorical side of perfumery, as well as contemporary claims, it is, however, necessary to rethink the relationship between the history of perfume and Orientalism, which is the subject of Part 2.

Notes

| ↑1 | Jessica Matlin, “Why Are We Still Describing Perfumes as Oriental?”, Harper’s Bazaar, May 26, 2021, online: https://www.harpersbazaar.com/beauty/a36503673/oriental-perfume-and-fragrance-backlash/ (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “The ‘Oriental’ category is being replaced by ‘Ambery’ on the fragrance wheel”, Trendaroma.com, June 28, 2021, online: https://www.trendaroma.com/the-oriental-category-is-disappearing-from-the-fragrance-wheel/ (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑3 | Mark Behnke, “Improving the Perfume Vocabulary for the Right Reasons”, colognoisseur.com, June 23, 2021, online: https://colognoisseur.com/improving-the-perfume-vocabulary-for-the-right-reasons/ (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑4 | Kira Haslett, “BSP to Replace Fragrance Descriptor ‘Oriental’ With ‘Amber’”, Perfumer & Flavorist, August 9, 2021, online: https://www.perfumerflavorist.com/fragrance/ingredients/news/21877642/bsp-to-replace-fragrance-descriptor-oriental-with-amber (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑5 | Michelyn Carmen & Ermano Picco, “Best Fragrances of 2021 (Ermano and Michelyn) + A Very Good Year Draw”, Ça Fleure Bon, December 26, 2021, online: https://www.cafleurebon.com/best-fragrances-of-2021-ermano-and-michelyn-a-very-good-year-draw/ (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑6 | “Les 7 familles de parfums”, The Fragrance Foundation France, online: https://www.fragrancefoundation.fr/education/les-7-familles-de-parfum/ (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑7 | Madison Park, “U.S. government to stop using these words to refer to minorities”, CNN.com, May 22, 2016, online: https://edition.cnn.com/2016/05/22/politics/obama-federal-law-minorities-references/index.html (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑8 | Charles Philipon, Le Charivari, May 29, 1854. |

| ↑9 | Advertising for Guerlain, Town & Country, Vol. 79, N° 3853, New York, USA, December 1, 1922, p. 19. |

| ↑10 | Advertising for Palmolive soap, Red Book Magazine, Vol. 18, N° 2, New York, USA, December 1911, p. 417. |

| ↑11 | Revue des marques de la parfumerie et de la savonnerie, August 1939, 17th year, n° 8, not paginated. |

| ↑12 | Edmond Roudnitska, Le Parfum, Paris, PUF, 1980, p. 11. |

| ↑13 | “Les familles olfactives”, Société française des parfumeurs, online: https://www.parfumeurs-createurs.org/fr/filiere-parfum/les-familles-olfactives-102 (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑14 | This question of epistemology is addressed by Patrick Tort in La Raison classificatoire, Paris, Aubier, 1989. A more specific approach to the classification of odors is proposed by Joël Candau & Olivier Wathelet in “Les catégories d’odeurs en sont-elles vraiment ?”, Langages, n° 181, 2011, p. 37-52. |

| ↑15 | We draw here on the seminal work of Roman Jakobson in “Deux aspects du langage et deux types d’aphasie”” (1956), Essais de linguistique générale, trad. N. Ruwet, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1963, p. 43-67. As Patrick Tort points out, this text is a first-rate clarification of the foundations of classification, even if the term is not specifically mentioned. |

| ↑16 | Patrick Tort, La Raison classificatoire, op. cit., p. 12. |

| ↑17 | Jean-Claude Ellena, Perfume: The Alchemy of Scent, translated by John Crisp, New York, Arcade Publishing, 2011. |

| ↑18 | Jean-Claude Ellena, Perfume: The Alchemy of Scent, op. cit. & Jean-Claude Ellena, Le Parfum, Paris, PUF, 2007, p. 53. |

| ↑19 | Edward Said, Orientalism [1978], London, Penguin Books, 2003. |

Comments