Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Feminine by definition but androgynous in essence, scent has been playing a game of smoke and mirrors with sexual identity ever since the birth of Jicky. From eau de Cologne to CK One by way of Thierry Mugler and Jean Paul Gaultier’s postmodern twists on stereotypes, fragrances have often blurred the boundaries between masculine and feminine notes. In fact, in its subversion of cultural conventions, scent may well be the subtlest expression of gender fluidity. On the occasion of International Women’s Day, we invite you to rediscover an article by Denyse Beaulieu originally published in Nez, the Olfactory Magazine – #03 – The Sex of Scent.

“Is it for men or for women?” It’s the question you’ll most often hear from someone smelling an unidentified fragrance. And that someone is usually a man, as though the very idea of wafting a scent conceived for the distaff side was deeply unsettling. And justifiably so. Perfume is insidious, mendacious, seductive; a mixture of secret ingredients blending artfulness and artifice. It is therefore, in the binary imagery of the West, feminine by definition; the polar opposite of wine, a noble product rooted in a terroir, authentic (in vino veritas) and hence, masculine. In the same way, fragrance notes are split evenly down the aisles of the virtual Sephora store. Gentlemen are allocated aromatic herbs, combustible spices and solid woods: clean, substantial, salubrious stuff. The ladies get the yielding, tender flesh of fruit and flowers: frail, moist, perishable materials. Since most people rely on gut feeling to assess fragrance, this gender divide is seldom questioned. It may even seem ordained by nature. Of course, should you go nosing around the Middle-East, you’d find that both sexes happily wear rose and oud: gendering scent is a cultural operation. And even in Western countries, it’s a fairly recent phenomenon.

An epicene creature

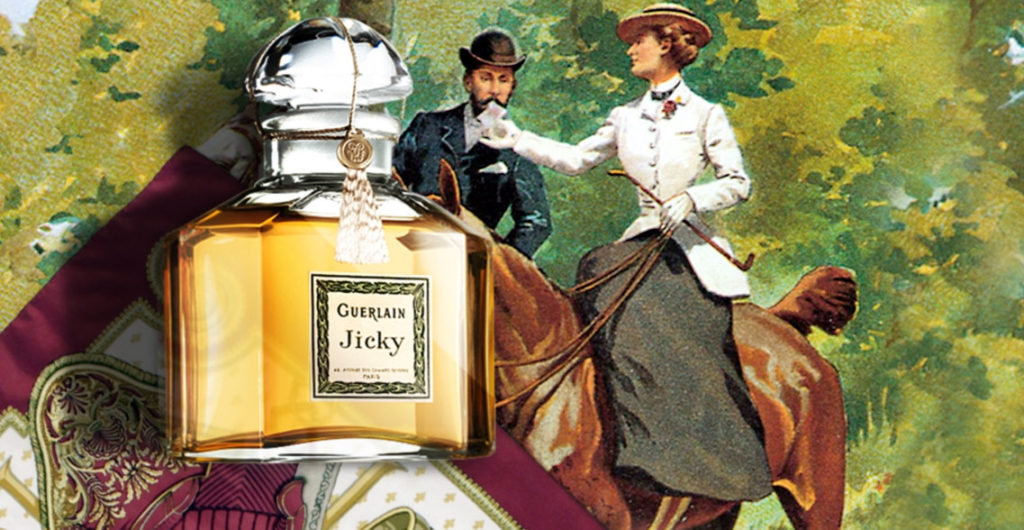

Who was Jicky (1899) intended for? Aimé Guerlain is said to have named it after some lost English love. Or was it his nephew Jacques’ nickname? Not that itwould have mattered much at the time: in the dawning days of modern perfumery, catalogues didn’t specify whether a product was meant for men or women. But Jicky’s ambiguity became a bit of an issue. Perhaps because the name stood for nothing in particular. Nor did its smell, unusually potent for the era since its formula was one of the first to feature synthetic ingredients. An epicene creature that smelled of clean linen (lavender), feral funk (civet), tarts (flowers) and sweets (vanillin and coumarin), Jicky somehow went against the grain. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the gender-queer juice gets name-dropped in Truman Capote’s Answered Prayers: he smells it on the famously bisexual French novelist Colette, who informs him that Proust wore it, or so she was told by Jean Cocteau (“But then he is not too reliable,” Colette adds).

In 1904, echoing Plato’s myth, Jacques Guerlain (aka God) split his uncle’s original androgyne, giving birth to a couple: Voilette de madame and Mouchoir de monsieur. Was the latter the first fragrance explicitly intended for the stronger sex? Its powdery, rosy lavender accords don’t feel especially hairy-chested. In fact, they practically make Jicky smell butch. But our reading of fragrance notes derives from cultural context, and Aimé Guerlain’s Belle Epoque androgyne was assigned a gender in hindsight, in the wake of its most illustrious descendent: Shalimar (it is said that Jacques Guerlain conceived the second by pouring ethyl-vanillin into the first). Though Jicky was initially seen as more of a masculine scent because of its lavender note, women in the 1920s, “being more receptive to the vanillin aspect because of a new amber oriental trend […] tended to categorize Jicky in the same family as Shalimar”, writes Marylène Delbourg-Delphis in Perfumer & Flavorist (June-July 1985). And Shalimar, which Jean-Paul Guerlain likened to “an evening gown with a sumptuous décolletage”, is undeniably feminine. Isn’t it a relief to know at last where you are sticking your nose?

For the Garçonne

But you never do, do you? Just as it seemed to have picked sides by merging with (exclusively feminine) haute couture, perfume went on a gender bender. In 1919, the survivors of the First World War had barely climbed out of the trenches clutching handkerchiefs soaked in Caron’s mawkish N’aimez que moi (“Love no one but me”), when they were hit with a snootful of the same house’s Le Tabac blond. Was it for men or for women? Neither. Inspired by Virginian tobacco cigarettes plucked from the lips of American doughboys, its author Ernest Daltroff was the first to offer a “masculine” note to women who smoked, the bob-haired Garçonnes, or flappers (the scent was actually more of a leather). The pioneering Daltroff would also be the first to pitch a masculine fragrance as “a fragrance perfume of youth and beauty”. Spiking wholesome lavender with sexy vanilla, Pour un homme (1934) drove the point home by featuring the statue of a Greek ephebe in its adverts.

Meanwhile, Gabrielle Chanel had taken her cue from Daltroff. An exquisite seismograph of the zeitgeist, she gave the Garçonnes the olfactory emblem of their emancipation by stripping down her own N°5 and sheathing it in Russian leather with Cuir de Russie (1924). In appropriating a note associated with virile pursuits (hunting, driving, flying), Chanel repeated what she’d done when she hijacked male sartorial codes. In a 1936 document in the Chanel archives, possibly intended for sales staff, the Cuir de Russie woman is described as “a tall, slender brunette whose moves are confident […] an opium cigarette between her lips, a bottle of whisky at hand”. Judging from the names they gave them, from Scandal (Lanvin, 1933) to Cabochard (meaning “headstrong”, Grès, 1959) by way of Révolte (Lancôme, 1936) or Bandit (Robert Piguet, 1944), fragrance houses were keenly aware of the transgressive charge of leather on a woman’s skin.

Bisexual scents

Conceived during the German occupation by Germaine Cellier, the first female nose to show up on the radar, the aforementioned Bandit is apt to throw every gender setting out of gear. What? Was that bouquet, carelessly stuck in an earth-filled ashtray, the kind of stuff they sold to Lauren Bacall’s contemporaries? But Cellier was prescient. When she paired up Bandit’s film noir dame with the technicolour diva of Fracas in 1948, she prefigured the sexual dimorphism that would overtake the perfume industry three decades later. Though Cellier’s hysterical tuberose produced no offspring for a quarter century, during the Reagan Era it would go on to spawn a brood of florals so outrageously femme that they would veer into drag queen territory – Giorgio Beverly Hills (1981) didn’t even bother to take a female stage name. As for Bandit, it’s as though it had acted as a place-holder for masculine perfumery, almost nonexistent at the time it came out. Bernard Chant used it as a template for the female Cabochard, which inspired, in turn, his male Aramis (1965) for Estée Lauder’s brand of the same name. The transition was such a success that Chant repeated it with Clinique’s Aromatics Elixir (1972), repurposed for men the following year as Aramis 900 Herbal (according to the perfumer Michel Almairac, it was the very same oil). Clearly, from the 1950s to the 1970s, bi-sexual scents didn’t put noses out of joint. Infact, from the liberation of France (Vent vert, Balmain, 1947, another Cellier) to Women’s Lib (Calandre, Paco Rabanne, 1969; N°19, Chanel, 1971), modern femininity usually translated into the androgynous verve of green notes. It wasn’t until the late 1970s that the olfactory polarity prefigured by the Bandit-Fracas couple took hold, as increasingly costly global launches demanded clear, blaring messages that could be understood from Texas to Singapore. Women were offered symphonic florals, such as Poison (Dior, 1985), Ysatis (Givenchy, 1984), Oscar (Oscar de la Renta, 1977). Men got aromatic fougères such as Drakkar noir (Guy Laroche, 1982) and Azzaro pour homme (1978). But though they seem to reflect stereotypes, Michel Almairac is quick to point out: “If these fragrances were successful, it’s because they had a strong identity. At the time, they were very innovative.”

Gender-free waters

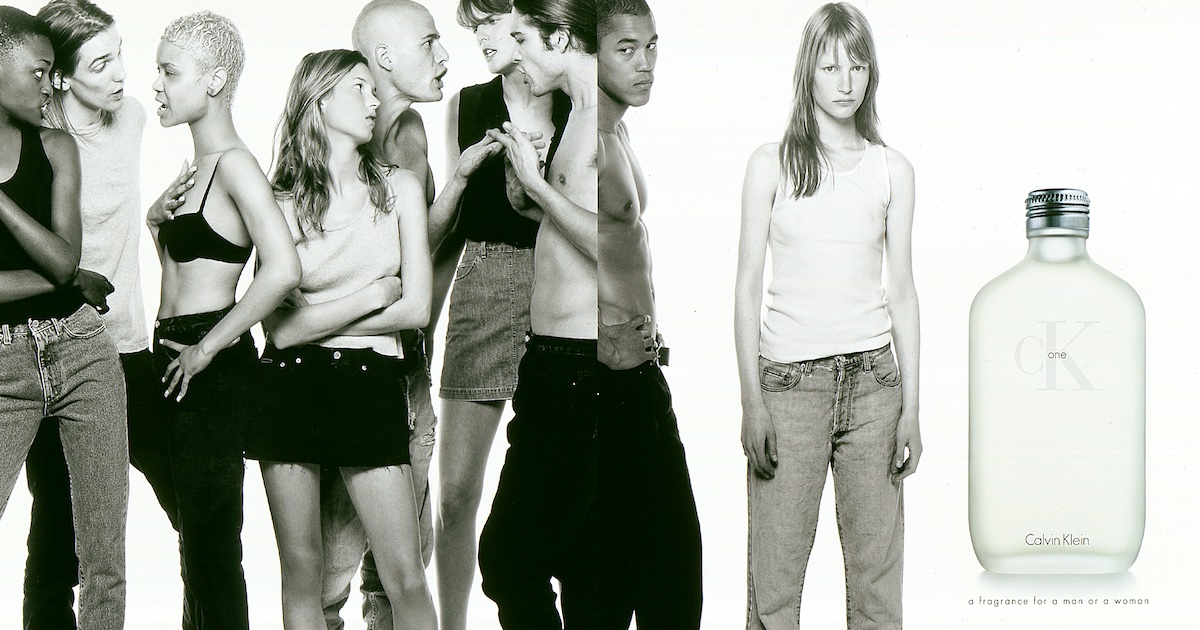

Meanwhile, ever since the 18th century, eau de Cologne had been following a course that touched both sides of the gender divide but embraced neither, providing a safe olfactory haven from the turmoil of successive sexual revolutions. In 1927, Jean Patou launched a citrus scent, Le Sien (meaning both “His” or “Hers” in French) for female athletes, who he was the first to dress with sportswear. “Sport is a field where men and women are equal”, stated the advert of the time. “A sportswoman needs a masculine perfume”, it went on, while granting that Le Sien was “also suitable for men”. In the 1960s, although Dior marketed Eau sauvage (1966) to men, Edmond Roudnitska conceived it as a unisex fragrance. “Its discreet yet long-lasting floral freshness is the very symbol of youth”, he wrote, and youth got the message: both sexes wore it to a man. The hugely successful Ô de Lancôme (1969) and Eau de Rochas (1970) would express a similar urge to break free from the clichés of seduction. “Don’t forget that women make the success of men’s fragrances,” Michel Almairac explains. “Not because they choose them for their husbands or boyfriends, but because they wear them.” And he knows whereof he speaks, since the masterful masculine floral he co-authored for Dior with Jean-Louis Sieuzac, Fahrenheit (1988), is one of the scents women love to filch. Calvin Klein’s CK One (1994) picked up where the Swinging Sixties eaux left off. Conceived as a reaction to the sexual hyperbole of the gaudy 1980s, it offered a pitch-perfect contemporary translation of the eau de Cologne’s universal appeal. Sold under the slogan “A fragrance for everyone”, Alberto Morillas’ composition was fronted by lesbian-chic model Jenny Shimizu, heading a tribe reconciling gender identities, sexual preferences and/or ethnicities in every gradient and combination around the most consensual of smells: a clean tee-shirt.

Sexual reassignment

Confronted with the vexing question of the gender of scent, Jean Paul Gaultier took the radically opposite tack with Classique (1993, composed by Jacques Cavallier) and Le Mâle (1995, Francis Kurkdjian). Rather than bypassing stereotypes by slipping under them like Calvin Klein had, Gaultier famously turned underwear into outerwear. The strumpet’s pink corset and the sailor’s striped top, cultural ready-mades appropriated as emblems by the couturier, were matched with two olfactory ready-mades. Classique’s rice powder accord and Le Mâle’s barbershop note may well have been the first openly claimed, ironic quotes of cosmetic notes in fine fragrance. Gaultier’s take on gender theory was playful enough no to spook mainstream consumers. Descended from Brut by Fabergé (“If he has any doubts about himself, give him something else”, said the 1970 advert), Le Mâle’s screaming queen of a fougère can also be worn with a straight face.

Thierry Mugler’s Angel (1992) also plays on the gender binary, but it inscribes it within the same heavenly body, sticking a patchouli beard over Angel’s cotton-candy rack, in Conchita Wurst style. Olivier Cresp had introduced his huge woody note to offset the sweetness of the candy-apple and praline accord. From there, wood wiggled its way into the women’s side of the aisle in the wake of Angel, but also Féminité du bois. Launched the same year by Shiseido, this “femininity of wood” spilled the beans on the note’s sexual reassignment. A descendant of Rochas’ Femme whose spices and dried fruit it reprises (Pierre Bourdon, who co-authored it, was Edmond Roudnitska’s student), it would become the template of Serge Lutens’ style, which would in turn be the matrix of niche perfumery.

Equal in rut

Born in the late 1970s as a backlash against the rising dominance of marketing in the industry, niche perfumery has, for the most part, refused to assign a gender to its products. Rather than an expression of male or female personas, its pioneers (L’Artisan Parfumeur, Diptyque) conceived perfume as a figurative note, a landscape, a travel memory; diverted from a mirror that sends back no reflection, the wearer’s gaze can turn to the olfactory form. Perfume becomes an aesthetic object, fostering a non-prescriptive approach that induces the wearer to produce her own interpretation. The erosion of gender differences by niche perfumery can also be perceived in mainstream perfumery, via the very “masculine”, dry ambery-woody notes that have seeped into feminine fragrances, or, conversely, the caramel notes incorporated into masculine scents like One Million. “Increasingly, we appropriate the smells of everyday life,” observes Michel Almairac. “We’re shifting towards fragrances that can be used by both sexes.” Conversely, niche perfumery seems to be shifting back to gendering – or, at least, toying with the notion. In a postmodern echo to the founding heterosexual pair, Mouchoir de monsieur and Voilette de madame, but also to Jean Paul Gaultier’s playful retromania, Arquiste’s Él and Ella conjure the disco era in Acapulco with a virid chypre for her, and a fougère on steroids for him. Both reprise styles typical of the time, but Rodrigo Flores-Roux introduces a further twist by rubbing these his’n’hers parfums trouvés against the same animalic notes, thus reintroducing – from behind, as it were – the smell of sex in the matter of gender. And proclaiming men and women to be equal in rut.

An invisible skin

Philippe Starck has long been haunted by the immaterial, as evinced by his Ghost chairs, his inflatable Le Nuage building in Montpellier or the WAHH spray, which delivers micro-particles in the mouth for a zero-calorie experience of flavour. The designer has now moved on to straight-up designing the air, with three fragrances inspired by skin, as the interface between the self and the elsewhere. But he hasn’t wholly vaporised the notion of gender. He envisions Peau de soie (Dominique Ropion) as “a perfume whose femininity wraps around a man’s heart”. And Peau de pierre (Daphné Bugey) as “a masculine fragrance that reveals a man’s feminine side”. Skin, after all, is a porous membrane, and genders contaminate one another. Starck’s perfumes translate his belief in the “22 gradients between heterosexuality and homosexuality” observed by scientists. “Yet we go on saying that there are men and women, which is ridiculous and totally reductive” he told the Swiss daily Le Temps (May 19th 2016). On this point, the composer, conceptual thinker and polymath Brian Eno – who has been known to dabble in scent – was already ten strokes ahead on the chessboard back in 1989. A founding member of gender-bending glam rock pioneers Roxy Music, and the inventor of ambient music, which he has described as “bisexual”, Brian Eno dedicated the booklet of his fragrantly-named CD Neroli (1993) to the theme of perfume. In an excerpt from an interview he gave to WNYC in September 1989, after the journalist brought up the Proustian flashback, Eno responded: “Another aspect of perfume that I think is interesting is in redefining sexual roles, gender positions.” Many women wear men’s fragrances, while some men use women’s classics, he explained. “It’s actually people saying that they’re crossing a certain gender line or saying that the traditional polarity of male and female doesn’t hold up – there’s a continuum from maleness to femaleness and you can choose your location somewhere along there,” said Eno. An invisible, indefinitely extensible skin, perfume doesn’t need to be “cut” to fit the curves of a body; each formula blends and blurs the boundaries between masculine and feminine note. In this respect, this particular fluid has always been the subtlest expression of gender fluidity.

- This article was originally published in Nez, the Olfactory Magazine – #03 – The Sex of Scent.

Main picture : CK One advertisement, Calvin Klein, années 1990 © DR

Comments