Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Sarah Bernhardt remains one of France’s most celebrated actresses, an extraordinary, freethinking woman who found fame across the globe in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Much has been written about her career, but little about the richly scented world in which “The Divine Sarah” lived and moved. To explore the subject, Eugénie Briot, a historian specialised in 19th-century perfumery, turned to Jean-Luc Komada, author of a book about the actress, La Ménagerie de Sarah Bernhardt. On the occasion of the centenary of her death this Sunday, March 26, 2023, we invite you to rediscover this article from Nez, The Olfactory Magazine #04 – Art and Perfume.

Charismatic, eccentric, and never tied by social convention, Sarah Bernhardt, whose remarkable acting talents, beauty, grace and distinctive voice propelled her to worldwide fame in a stage career lasting almost six decades, indelibly marked the tumultuous era in which she lived, and her personality continues to fascinate today. From her beginnings at the French national theatre company La Comédie-Française in 1862, aged just 18, up until her death in 1923 at the age of 78, Bernhardt played more than 120 characters, including Marguerite in La Dame aux camélias (Camille), Dona Sol in Hernani, and the queen in Ruy Blas. She notably broke with tradition to play male parts, such as the title role in Hamlet, Lorenzo in Lorenzaccio and Napoleon II in L’Aiglon. Her unusual career took her to stages across Europe, North and South America and Australia, and into the early productions of cinema. Behind the scenes meanwhile, whether at home in Paris or at her beloved holiday home on a Breton island, Bernhardt lived in an often eccentric style that was bathed in rich scents. Jean-Luc Komada, a graduate of the French business school ESSEC and the Paris École Boulle school of fine arts, first discovered the world of Sarah Bernhardt as a child, when playing in the remains of her derelict holiday home on Belle-Île in Brittany. His long research into her life resulted in a book he published last year, La Ménagerie de Sarah Bernhardt, a fictional work which portrays the actress through imagined correspondence between those close to her. Here, Komada and Eugénie Briot, a historian and expert on the development of 19th-century perfumery, offer a rare insight into the rich and often heady olfactive world that surrounded the actress, the first to become an icon of a cosmetics brand.

Eugénie Briot: I know Sarah Bernhardt through my interest in the 19th century, a period which saw her become the first international star, one for who Jean Cocteau invented the expression “monstre sacré”. How did you come across her?

Jean-Luc Komada: It was at the Citadelle Museum at [the Breton island of] Belle-Île-en-Mer. Nanie Clément, a tour guide, gave me a passionate introduction to Sarah Bernhardt through personal objects, her own sculptures and paintings, and some documents and posters of her shows. I was six years’ old. That first encounter was a revelation. As a child, I often played in the fort at the pointe des Poulains, which at that time was abandoned and derelict, where Sarah Bernhardt had lived. It had a particular atmosphere. Although it was empty, it still felt lived in. Little by little, I got to know her, became immersed in her world and imagined her conversations, her tastes, her perfumes.

E.B. If we imagine the perfumes she could have worn, it is inevitable that she would have smelt such legendary creations as Fougère royale, Jicky, Après l’ondée, L’Origan, Quelques fleurs, Chypre de Coty and even N°5! As fragrances by renowned perfumers of the era, they could not have escaped her nose. She would also, when washing, have no doubt used eau de Cologne, which was in its heyday in the 19th century. But above all she witnessed the aesthetic revolution in perfumery at that time, with the introduction of phenomenal synthetic molecules such as heliotropin, coumarin, vanillin, isoamyl salicylate, the first musks, ionones, aldehyde C-12. The whole of modern perfumery was born in that era. It saw the appearance of new olfactory families: the fougères, the orientals, the chypres. Such a transformation! As for saying which were her favourite perfumes, sources are rare, unfortunately.

J-L.K. Her friend, the composer Reynaldo Hahn, wrote, “Sarah Bernhardt’s perfume is so pervasive that when she presses against your arm, your sleeve reeks of it for several days”. We can therefore assume she chose the more heady perfumes. She liked white lilies, like the ones she is always surrounded by on the posters by [Czech decorative artist, Alphonse] Mucha, and camellias in memory of the heroine of La Dame aux camélias who she played so many times. She loved wearing little bouquets of fresh flowers pinned to her dresses, and violets sewn into her low-cut top.

E.B. There was a huge craze for flowers in the 19th century, especially violets. For wealthy women, they were a daily purchase. In Paris, the markets got bigger, like the one at Quai Desaix – now Quai de la Corse – or the one at Les Halles, and flower stalls multiplied in the streets of larger French towns. Flowers spilled into people’s homes and became an essential element of every woman’s dress style, from duchesses to lowly servant girls. Lilies are usually associated with purity and violets with modesty, each flower has its own meaning and combining them in bouquets is a lost art, yet it allowed for the sending of real messages. Certainly, Sarah Bernhardt perfectly mastered this language of flowers. But aside from the flowers, what other olfactory elements could be found in her home?

J-L.K. We must imagine her apartment on the rue de Rome [in Paris] as a colourful jumble of miscellaneous objects. The floor was covered with Oriental rugs and strong-smelling polar bear and ocelot furs on which birds, big cats, dogs and small cats with charming, fanciful names lived and frolicked. Between 1894 and 1922, Sarah Bernhardt spent her holidays each summer at the pointe des Poulains, on the north coast of Belle-Île-en-Mer. Photographed in her bedroom, she can be seen surrounded by lots of trinkets, art objects, wall hangings, rugs, with a dog at her feet and flowers cascading above her. We can imagine a very distinct olfactory environment, where the fragrance of flowers mixed with animal scents – which she masked with strong perfumes. The author Jules Renard observed: “Not only were the lounge and other rooms filled with the scent of these bouquets, usually made of lilies and camellias, but they were also saturated with the clinging, pungent essence of amber and jasmine that the actress spread about, shaking the contents of bottles directly on the curtains and cushions.”

E.B. At the end of the 19th century, decorative arts became very elaborate and ornate. Dozens of small objects would be placed together in a setting where textiles were very important – rugs, wall hangings, blankets, upholstered furniture. We can indeed imagine the air was very heavy and it would not have been easy to get rid of the smell of dust that must have been on all these textiles.

J-L.K. Don’t forget that Sarah Bernhardt was also surrounded by an impressive menagerie of animals! In her home, a puma kept company with a monkey or a parrot, a cheetah lived alongside various dogs, turtles, a boa, a chameleon and a host of winged creatures. All these animals impregnated the environment with their musky smells, tenacious odours which mixed with the flowers, the textiles and her favourite perfumes. But her domestic smellscape superimposed itself on the natural environment, which came with its own powerful odours. When she was living in her small fort at Belle-Île-en-Mer, Sarah Bernhardt liked to go to the headland facing out to sea and recite lines written by her friend, Victor Hugo, either to seek inspiration or to exercise her powerful voice. To get to the cliff, she crossed her garden planted up with tamarisk, and the moor, filled with the fragrance of gorse and broom. She inhaled deeply into her lungs the immortelle flowers of the Côte Sauvage, mingled with the salty freshness of the sea spray. Maybe the smell of the salted butter caramels made in the little neighbouring village also mixed in with the spiced warmth of the small yellow flowers and the bitter-sweet balance of violets and gentian. She was bathed in a very complex olfactory world, which reflected her own personality. This olfactory evocation in fact led to a composition imagined by perfumer Alexis Dadier.

E.B. This strong personality, closely linked to the world of cosmetics by her profession, attracted the attentions of brands to the point that she was often portrayed as the first modern icon of advertising.

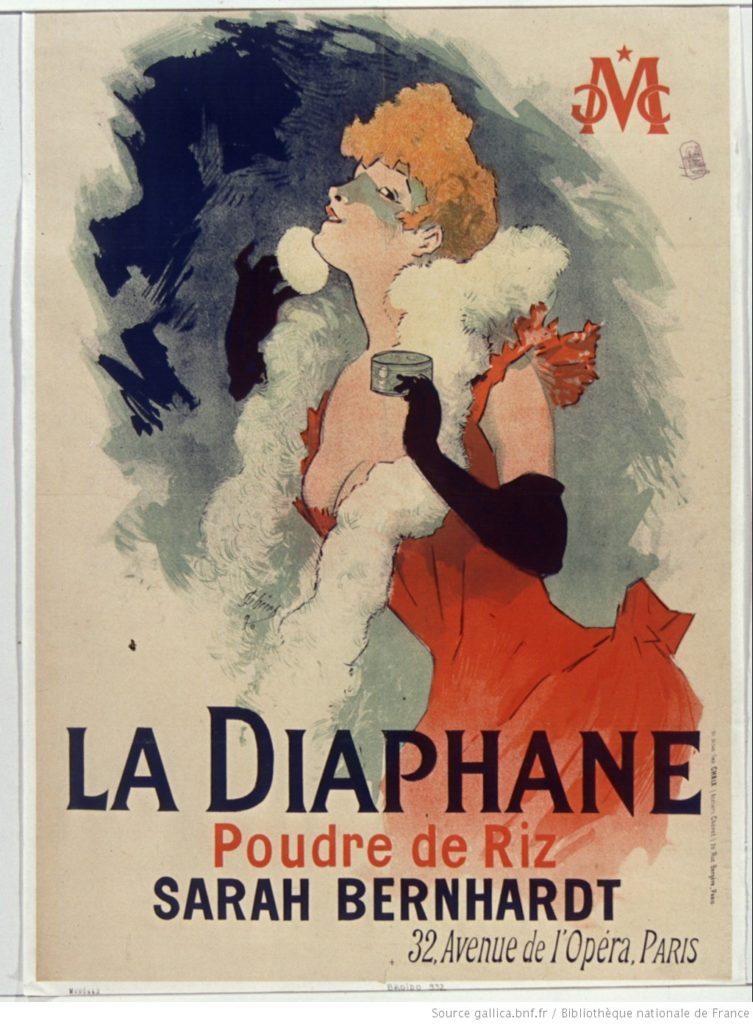

J-L.K. She was a performer with unequalled fame, in America as much as in Europe. The brands very soon capitalised on her charisma. The fact that as an actress she had so often been pictured, particularly by Mucha, in posters advertising her shows, meant her face was glorified and iconic. In the 1890s, she was the face of La Diaphane face powder, by perfumery Mazuyer & Cie, whose publicity posters were designed by [French painter and lithographer, Jules] Cheret. The closeness and evident nature of the link between her personality and the product made her the first icon, the one who opened up the path to the use of the image of actresses to promote brands globally, and to build the founding pillars of these industrial areas.

Source : Gallica.bnf.fr

E.B. It’s a role which indeed had always been reserved rather for royalty. And when Guerlain formulated Eau de Cologne impériale [in 1853] for the occasion of the marriage of Eugénie de Montijo and Napoleon III, the perfumer was no doubt seeking aristocratic endorsement for the product, but he was careful to present it in the form of a tribute to the new empress. To give this role to an actress marked a very important change of perspective and opened an avenue that was promised a long future. Without Sarah Bernhardt as their official brand ambassador, some brands appeared to build their advertising campaigns around women who looked like her – red hair, curls – and if necessary calling on Mucha himself to draw them. The example of the Rodo lance-parfum [a vaporiser] is so revealing: the woman pictured is not Sarah Bernhardt but she looks like her and the brand was happy to play on the ambiguity, which speaks volumes about the effectiveness of using her image.

J-L.K. Her aura was immense and seemed to eclipse everything around her. The perfumery Mazuyer & Cie was to become, several years later, the Perfumerie Diaphane – the name of the product becoming the name of the perfumery itself – and the powder became totally associated with its icon, very often being called “Sarah Bernhardt powder”. She was a unique artist, of a rare outreach, who would have a marking effect on artistic, political and socio-cultural circles over several generations.

La Ménagerie de Sarah Bernhardt by Jean-Luc Komada is published in France by Publishroom, priced 21 euros.

Main visual: Sarah Bernhardt photograph by Sarony Napoleon, 1891, Theatrical Cabinet Photographs of Women (TCS 2), Harvard Theatre Collection, Harvard University. Source: Wikimedia commons

This article was originaly published in Nez, The Olfactory Magazine #04 – Art and Perfume.

Comments