Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

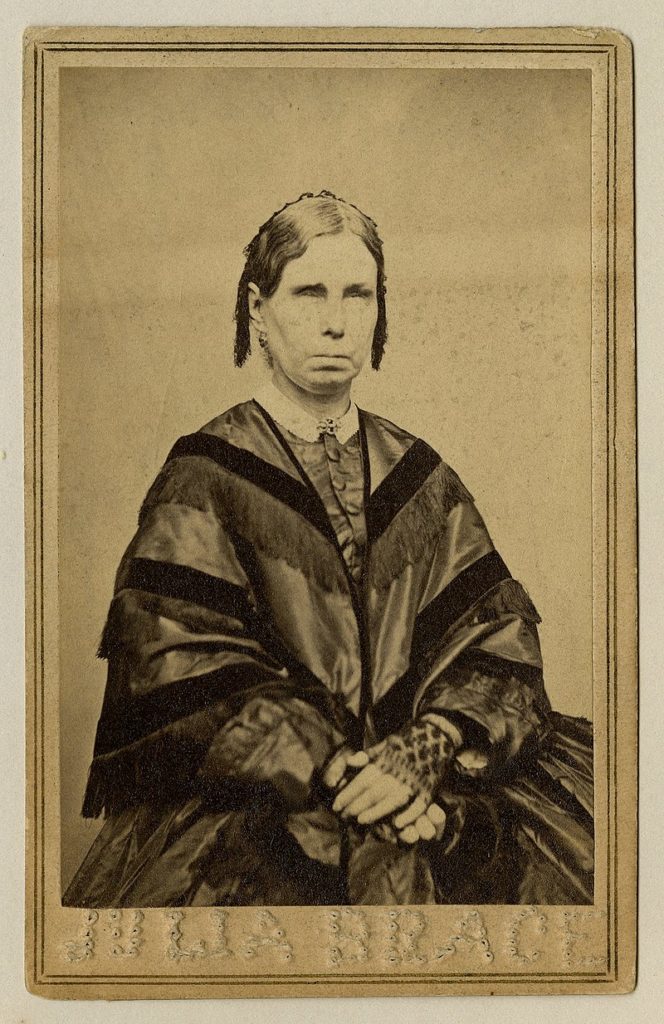

On June 27, we celebrate the birthday of Helen Keller (1880-1968), an American author and activist who lost her sight and hearing at the age of 2. The development of her sense of smell, as well as her perception of the world in general, are analyzed here by scent historian Caro Verbeek. It’s also an opportunity to discuss the lesser-known case of Julia Brace (1807-1884), also deaf and blind and who was a student and later employee of the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut.

When tasked with thinking of famous historical figures who were deprived of both their sense of sight and hearing, the name Helen Keller will likely spring to mind for many. The author stood out not only among her peers, but in general, because of her eloquence and intellect. She is still known today because of her often-reprinted autobiography, The Life of Helen Keller. The oldest of two children, Helen was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama, where she grew up. After she had lost her sense of sight and hearing at the age of 2, her tutor Anne Sullivan taught her how to communicate through the sense of touch. Being so young, she only learned about the mere existence of words when Sullivan held her hand under flowing water and wrote the sign for “water” in her palm. Her haptic sense and her sense of smell became her primary senses to gain knowledge, navigate, communicate, appreciate art and, as she expressed it, to acquire happiness. Her faculties of touch and smell – being intimate in nature because they require proximity – became extraordinarily acute and enabled her to understand the world even beyond an arm’s length. They eventually helped her grasp philosophical concepts such as love and beauty, even though these can neither be touched nor smelled, at least not directly. Her descriptions of and reflections on the world we all share and the artworks in it are incredibly deep and thorough, and are also applicable to those who can see and hear. I would argue that most of us would see and hear more if only we’d start using all of our senses to their full potential.

Helen Keller is especially well-known in the “scent community” and regularly quoted by scent experts because she described smell as: “[a] potent wizard that transports you across thousands of miles and all the years you have lived. The odors of fruits waft me to my southern home, to my childhood frolics in the peach orchard. […] Even as I think of smells, my nose is full of scents that start awake sweet memories of summers gone and ripening fields far away.”[1]Helen Keller, The World I Live in, 2013, originally printed in 1908.

This quote was published two decades before Proust’s famous novel In Search of Lost Time, in which he describes what is now called a Proustian memory (which refers to an unintentional associative memory that can be easily conjured by smell, this sense having a central place in Proust’s work). We will return to her extraordinary sense of olfaction shortly, but only after exploring how she engaged with the world, and even music, through yet other senses.

A “reorganization” of perception

Naturally, deaf and blind individuals have to resort to other senses, but not by merely compensating for a lack of the lost ones. People often assume the available senses become more acute, but, as sensory and disability expert Piet Devos explains, it is rather a “reorganization of perception.” Input from different senses is combined in new ways, as the world of deaf and/or blind persons is constructed around different perceptual categories from those of the majority who can see and hear. Visual “reality” differs dramatically from haptic reality.[2]“Haptic” refers to the sense of touch in the broadest sense, so not just cutaneous (skin contact), but also the sensation of pain, heat, shape, vibration, etc. For example, a seeing individual experiences their own body as being at the center of their surroundings, whereas this center shifts and absorbs that which is being touched for the visually impaired. Of course, Helen Keller came to rely heavily on her senses of touch, smell and – as I will briefly demonstrate – vibration, but moreover, there was a recalibration of how these senses collaborate.

Haptic beauty and Beethoven’s vibes

Helen Keller traveled the country to visit cultural, technological and natural sites. She was overpowered and in complete awe of the violence and greatness of Niagara Falls, which she felt in her entire body. But even the tiniest objects could enchant her: She was thrilled by the soft vibrations of the wings of delicate insects, trapped in flowers that she gently squeezed without harming them.

Vibration also enabled her to enjoy Beethoven’s famous Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 (composed when Beethoven himself was going deaf), which she experienced through the radio. She placed her hands on it after someone had taken off the case surrounding it: “What was my amazement to discover that I could feel, not only the vibration, but also the impassioned rhythm, the throb and the urge of the music! The intertwined and intermingling vibrations from different instruments enchanted me. I could actually distinguish the cornets, the roil of the drums, deep-toned violas and violins singing in exquisite unison. How the lovely speech of the violins flowed and plowed over the deepest tones of the other instruments!”[3]Helen Keller, The Auricle, Vol. II, No. 6, March 1924. American Foundation for the Blind, Helen Keller Archives.

She experienced the aesthetic dimension of sculptures that she was allowed to touch in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and meditated on the true nature of visual art: “I sometimes wonder if the hand is not more sensitive to the beauty of sculpture than the eye. I should think the wonderful rhythmical flow of lines and curves could be more subtly felt than seen.”[4]Helen Keller, The Story of My Life, Bantam Books, 1988, originally printed in 1903.

Rhythm isn’t reserved to a single sense and can be seen, heard and felt, both with the skin and the internal sense called “kinesthesia,” which is an interoceptive sense that makes us feel movement, weight, and the position of our limbs and bodies in space. Helen Keller couldn’t just sense rhythm, but also artistic intention and emotional states: “Museums and art stores are also great sources of pleasure and inspiration. […] I derive genuine pleasure from touching great works of art. As my fingertips trace line and curve, they discover the thought and emotion which the artist has portrayed. […] My soul delights in the repose and gracious curves of the Venus; and in Barré’s bronzes the secrets of the jungle are revealed in me.”[5]Ibid.

While the fact that haptic sensations can lead to aesthetic pleasure and knowledge might ring true to the seeing and non-seeing alike, Keller was – and rightly so – often surprised at how people could forget that not all sensations reach us through the eye and ear: “They forget that my whole body is alive to the conditions about me. The rumbles and roars of the city smite the nerves of my face, and I feel the ceaseless tramp of an unseen multitude, and the dissonant tumult frets my spirit.” [6]Ibid.

The fact that beauty transcends visual appearance wasn’t accepted by everyone (and not much seems to have changed, especially since the birth of social media platforms such as Instagram). Keller reminisces in her autobiography how a lady wonders how she can appreciate flowers not being able to see their splendid colors. Keller answers that flowers have so many other qualities, their petals delicate to the touch, and their fragrance not only pleasant but also functioning as a doorway to dear memories, for example of spending time with her loved ones. But not willing to accept her explanation, her interviewer bluntly comes to the conclusion that she can probably discern all the hues with her hands. This is a clear example of an ocularcentric approach to reality and complete ignorance to the fact that touch and smell can function as portals to aesthetic and contemplative experiences just as well, if not more effectively.

An extraordinary sense of smell

Helen Keller wondered if there was any sensation deriving from sight greater than “the odors that filter through sun warmed, wind tossed branches.”[7]Ibid. One day she was engaging in one of her favorite activities, sitting in a mighty tree, enjoying the sun on her face, the soft breeze on her cheeks, the sensation of the delicate foliage and – as in a poetic opposition – the rough bark and its sweet green smell (Keller could identify many trees by their distinct scents). Her teacher Anne Sullivan – who almost always guided her – briefly left to pick up something from their nearby house, telling her pupil to sit perfectly still. But suddenly the young girl noticed something was amiss and disaster was about to strike. The ambient scent had dramatically changed, and she knew a thunderstorm was approaching and that it was essential to hold on to the tree for dear life. Seconds later, a fierce wind started to beat the tree, shaking her heavily. Keller was unable to jump down, completely disoriented and absolutely mortified, until finally she was rescued by Sullivan.

This is just one example of the pivotal role the sense of smell played in Helen Keller’s life. Besides using her nose to be aware of danger (something we all use it for, albeit unconsciously most of the time), she was also able to smell professions such as tailors or bookkeepers, or the proximity of certain people and objects. Perhaps unsurprisingly, she deemed smell the most important of all senses, even to seeing people, although they probably weren’t aware of it, she concluded. As she framed her argument, why else would people burn sweet frankincense in the presence of god(s)? And why else would smell influence our behavior so greatly? Stench even makes people flee, whereas fragrances add greatly to our well-being, and makes the heart “dilate joyously, or contract with remembered grief,” she wrote in The World I Live in.

The forgotten case of Julia Brace (1807-1884)

Helen Keller was in touch with and aware of other deaf and blind contemporaries. In her autobiography she mentions a girl named Ruby Rice, whose sense of smell must have been extremely well developed, for “when she enters a store, she will go straight to the showcases, and she can also distinguish her own things.”[8]Helen Keller, The Story of my Life, Letter to William Wade, December 9, 1900. But not nearly all people of this disposition (as is the case with seeing and hearing people) have such a keen sense of olfaction (and not nearly everyone with such a fine sense of smell can use it to navigate and move around). It must have been innate and flourished because of the situation.

Although relatively forgotten today, Julia Brace was also lauded in newspapers and by contemporary poets, who noted that she was “remarkable, even among the deaf-blind, for the extreme delicacy of her sense of smell.”[9]William Wade, “A List of Deaf-Blind Persons in the United States and Canada”, American Annals of the Deaf, 1900. And an article from the Connecticut Herald in 1917: “Her sense of smelling is remarkably exquisite and appears to be an assistant guide with her fingers and lips.”

After reading this, as a scent historian, I was curious to find more concrete examples of her outstanding faculties to share with a wider audience. But I would first like to sketch a brief outline of her life.

Brace was born in 1807 and was one of the first known educated deaf and blind individuals. After a severe case of typhus, she lost her sense of sight and hearing at the tender age of 5. As might be expected, she didn’t immediately realize what was going on. At first, she wondered why her mother didn’t turn on the lamp, thinking the night had veiled the visible world. And after repeating her question and not receiving any response, she thought her mother – who was holding her hand – simply refused to reply to her. “Why don’t you answer me?” she allegedly cried. It must have been excruciatingly hard for her to find out there would be infinite darkness and silence forever. But this silence and darkness were only relative, as they would be lifted by her special education, and of course partially compensated for by her other senses.

Communicative touch

When Julia Brace lost two of her senses, she already knew the concept of words and language (unlike Helen Keller). Since she was now deprived of the children’s usual way to communicate, she had to find another method: the sense of touch. This sense also enabled her to become a fine craftsperson, occupied with needlework, and at some point, even creating beautiful shoes, which were exhibited in 1824 and mentioned in a local Boston newspaper. According to several accounts, she both used her hands and tongue to work the needle. She also used her hands to read facial expressions, and would place them on the mouth and eyes of her little sister to ascertain whether she was happy or sad, laughing or crying.After her poor parents could no longer take care of her, and funds were raised to help them out, she started attending the American School for the Deaf. Eventually, she was hired there after graduating. Her (somewhat simple) use of tactile sign language, also called the “manual alphabet” – which consisted of signs written in the palm of the hand – was picked up by visiting professor Samuel Howe from the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston. He started using it for his own pupils, which also benefited Helen Keller years later. Only in 1842 did Brace enter this school herself, where she was finally educated in reading and writing, although she only attended this institution for a short while. Brace died at the age of 77.

On following one’s nose: Thresholds of smell

Like many other children that grow up deaf and blind, Julia Brace learned to identify (and of course enjoy) objects, people and circumstances by their scents. She explored flowers and plants by touching and smelling them, as we can read in a poem by J.C. Bridgewater from 1844 dedicated entirely to Brace:

“The genial influence of spring wakes her lone heart to gladness;

And she gathers the first flowers and even the young blades of grass

And inhales their freshness with a delight bordering on transport.”[10] J.C. Bridgewater, Songs in the Shade – on the Account of an American Girl, Born Deaf, Dumb and Blind, 1844.

Another account makes clear how flowers contributed to her well-being: “She often wanders in the fields, and gathers flowers, to which she is directed by the pleasantness of their odor.”[11]Anonymous, “Deaf, Dumb and Blind Girl, The Recorder”, The Connecticut Herald, December 16, 1817.

But most remarkably, Brace used her nose to orient herself and navigate – and very successfully so. When she enrolled in a new school, according to some of her classmates, she actually stooped to sniff thresholds, turning them into olfactory landmarks. Indeed, thresholds don’t just mark spaces kinesthetically and visually, but also olfactorily, for example because of the function and activities in certain spaces that come with different scents. According to the famous smell mapper Kate McLean, with whom I immediately shared this astonishing fact, this makes a lot of sense, because thresholds are dynamic, transitory connectors and separators that signal spatial movement. In these spaces smells blend and merge from the rooms on either side. In the Perkins School, for example, the Library/Tower threshold was a narrow doorway where distinct, static and resident aromas of paper, card, leather, glues and wood dominated on one side and dynamic, transitory warmth of passing bodies, replete with smells of individuals and groups of people mingling dominated on the other side. Who could fail to notice such a difference in smell temperature and combined olfactory components? Following a visit to the Perkins School, McLean dedicated a study, map and article to “threshold scents” in Greenwich Village in New York City. Her article says: “Thresholds explore the doorways, portals and spaces between the street and building interiors. There are distinct ‘street smells,’ specific ‘store smells,’ and a range of ‘shared smells’ that belong neither inside nor outside.”[12]Kate McLean, “Thresholds of Smell – Greenwich Village”, published online: https://sensorymaps.com/?projects=nyc-thresholds-of-smell-greenwich-village

She investigated which scents were captive in a space and which ones transgressed from building to street, or from space to space within buildings. As McLean concluded: “The richest combination of smells was located on street corners where humans, activities and winds intersect.” Perhaps Brace would have agreed, and considering the way she navigated, it seems plausible indeed. It is certain that due to her nasal sagacity, Brace knew her way around in no time and moved on campus autonomously.

Unknown to most seeing people, something fundamental in relation to thresholds has changed since the energy crisis and this especially affects the blind and the visually impaired. Mirjam Boers – a blind Dutch social worker – shared: “Since the crisis, stores have closed their doors this winter to save on energy; it makes it harder for me to find the entrances. Scents are helpful clues to locate doorways.” Upon telling her about Brace, she added: “I clearly remember every classroom or other spaces in school having their own distinct smell, as did the teacher, that also influenced the ambient scent in the several spaces. I would always know who was teaching before hearing their voice.” If we follow Brace’s, Boers’ and Kate McLean’s observations, it would be worthwhile to “stop and smell the thresholds” at least once in a while.

Not silent or dark, but bright, fragrant and beautiful

We tend to think that deafness and blindness lead to silence and darkness and that the people deprived of sight and hearing can neither experience beauty nor learn about the world beyond an arm’s length. But the reality of Helen Keller and Julia Brace proves this is not only incorrect, but a missed opportunity for all of us. Concepts, language and even “visual” art can be perceived in different ways, ways that might even be more gratifying and lead to a deeper, fuller understanding of the essence of things. In the end, all the senses, especially when combined, can give us access to a realm beyond the directly perceivable.

- Dr. Kate McLean – specialized in smell mapping and lecturer at the Graphic Design programme at University of Kent – authored the paragraphs on olfactory navigation.

- The author would like to thank literary scholar and expert in disability studies Dr. Piet Devos (Belgium).

Main visual: Helen Keller, Century Magazine, January 1905. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Notes

| ↑1 | Helen Keller, The World I Live in, 2013, originally printed in 1908. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Haptic” refers to the sense of touch in the broadest sense, so not just cutaneous (skin contact), but also the sensation of pain, heat, shape, vibration, etc. |

| ↑3 | Helen Keller, The Auricle, Vol. II, No. 6, March 1924. American Foundation for the Blind, Helen Keller Archives. |

| ↑4 | Helen Keller, The Story of My Life, Bantam Books, 1988, originally printed in 1903. |

| ↑5, ↑6, ↑7 | Ibid. |

| ↑8 | Helen Keller, The Story of my Life, Letter to William Wade, December 9, 1900. |

| ↑9 | William Wade, “A List of Deaf-Blind Persons in the United States and Canada”, American Annals of the Deaf, 1900. |

| ↑10 | J.C. Bridgewater, Songs in the Shade – on the Account of an American Girl, Born Deaf, Dumb and Blind, 1844. |

| ↑11 | Anonymous, “Deaf, Dumb and Blind Girl, The Recorder”, The Connecticut Herald, December 16, 1817. |

| ↑12 | Kate McLean, “Thresholds of Smell – Greenwich Village”, published online: https://sensorymaps.com/?projects=nyc-thresholds-of-smell-greenwich-village |

Comments