Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

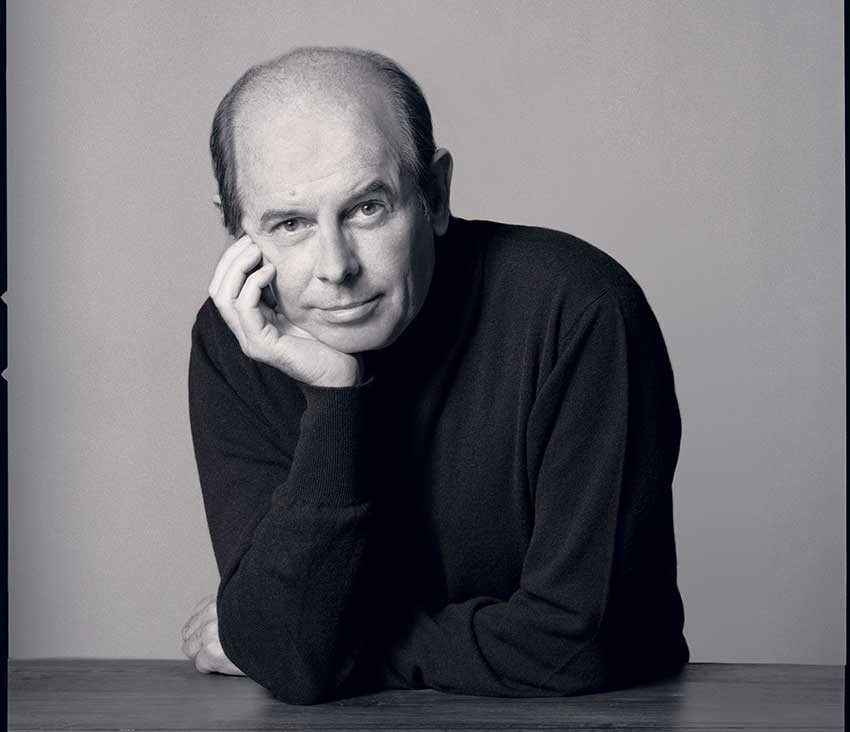

All perfume lovers know Legendary Perfumes. French Feminine Fragrances, published in 1996. With this book, Fragrances of the World’s founder Michael Edwards was the first to give perfumers the opportunity to speak out in order to collect in detail and without detour the entire genesis of the great classics of perfumery.

Twenty-three years later, he offers an expanded version with eight new legends (Fracas, Nahema, Féminité du bois, J’adore, Flower, Coco Mademoiselle, Timbuktu, Portrait of a Lady), and enriched texts on 52 creations, gathering testimonies and quotes from perfumers, couturiers, artistic directors, designers….

Edwards describes himself more as a “word weaver” than as a writer, because most of the legends’ texts are the words of the creators. He continued his research and investigations through the archives of perfume houses and conducted some 200 interviews, in order to transcribe a history of perfumery as accurate as possible to reality, rid of its myths and legends, of formatted, distorted or sublimated speeches by certain journalists, biographers or unscrupulous press officers. The result is a living testimony to the history of perfumery, since, as the author points out, “in a world where perfumes are modified, sometimes destroyed, we have no museums that allow us to examine what happened”. This is why he strives to reconstruct this past as closely as possible through the words of the creators themselves, by listening to them and “weaving” their words.

We met him in June in his Parisian apartment, in the Saint-Michel district, where he gave us a few glimpses of his new work through two emblematic creations by Chanel: the famous N°5, often covered in sometimes improbable legends, and Coco Mademoiselle, the feminine global best-seller which was initially intended to be only a small flanker… Interview.

How did Coco Chanel come up with the idea of creating a perfume? You say in your book that two versions coexist: it would be either her friend Misia Sert or the Grand Duke Prince Dmitri Pavlovitch who would have influenced her?

Misia Sert wrote that she gave Chanel the idea for a perfume in 1920, while reading aloud from a newspaper article. That may be true but but Mlle Chanel had already registered the name “Eau de Chanel”, in 1919. So clearly, there were always this premise that there might be a perfume. Was it because of Poiret or Coty, whose perfumes had become increasingly important? Probably.

However, the idea turned into reality when, during the summer of 1920, Chanel was invited to visit Parfums Rallet in La Bocca, near Cannes. There, she was introduced to perfumer Ernest Beaux.

At the beginning, Chanel was hostile to the idea of a fragrance: “I’m a couturier, not a perfumer, and I disapprove of everything perfumers do.” she said. How did her meeting with Ernest Beaux go?

Beaux rarely spoke publicly of his collaboration with Chanel. Once in a speech, he said that he had presented ten perfumes to Chanel which he had created between 1919 to 1920. The perfumes were ordered in two series : 1 to 5 and 20 to 24. She selected four of them, he said : 5, 20, 21 and 22.

At that time was it common to work like this? Were there any exchange between the perfumer and the client? Any reworks? Or just a selection?

Beaux said that he had already created all the perfumes he showed Chanel. His letters demonstrate that he had been working on N°5 for at least five years. He finished it, he said, in 1920, before he met Chanel.

There is no evidence that Coco Chanel told him to rework the formula, make it stronger or more expensive. To the contrary, Beaux would not have permitted to anyone to tell him what to do!

Finally a perfumer would work like a couturier? “You like it, you buy it!”

Exactly, but of course as clients work with perfumers and develop their confidence, the more likely they are to ask for modifications.

So when did this habit of asking for modifications start?

From the start, I assume. Jean Patou started to rework Joy (1930) with Henri Almeras, for example, telling him to “Make it stronger, make it stronger!”, but he would not have gone into perfumery technicalities such as “Make it more aldehydic…”.

Author Ludovic Bron said about N°5: “In the realm of perfumery, it was a sort of French Revolution.” What did he mean?

It was an abstract flower, an imagined floral in an era when perfumes copied nature. Yes, it became famous for its innovative use of aldehydes but Jacques Polge, Chanel’s perfumer, once told me that you can take the aldehydes out of N°5 and it would still remain N°5.

Beaux once said he put the aldehydes to make the richness of the flowers (the jasmine, the May rose, the ylang-ylang) explode.

There’s an old story that the high level of aldehydes in N°5 was the result of a mistake. when his assistent misinterpreted his instruction and did not dilute the aldehyes to a 10% level. It’s been repeated so often it’s assumed to be true but it makes no sense simply because Beaux used a cocktail of three aldehydes in N°5. One mistake, fine, but three ?

This is part of the legend, of the myth of N°5 ? Where does it come from?

From Mademoiselle Chanel, a tell-all biography published by the tabloid Paris Match and released several months after Chanel’s death. The book, riddled with factual errors, was written by Paris Match’s secretary general Pierre Galante, who never interviewed Chanel about her life story, but claimed to have amassed “hundreds of eyewitness accounts” in the few months it took him to pen the manuscript.

Ernest Beaux talks about his military service near Arctic Circle. How did his experience influence the creation of N°5?

Beaux wrote that he had been sent to spend a part of the Allies’ Russian campaign in a Murmansk above the Arctic Circle “at the time of the midnight sun when the lakes and rivers release a perfume of extreme freshness. I retained that note and replicated it.” The scent of the water plants was fresh and sharp, full of aldehydes.

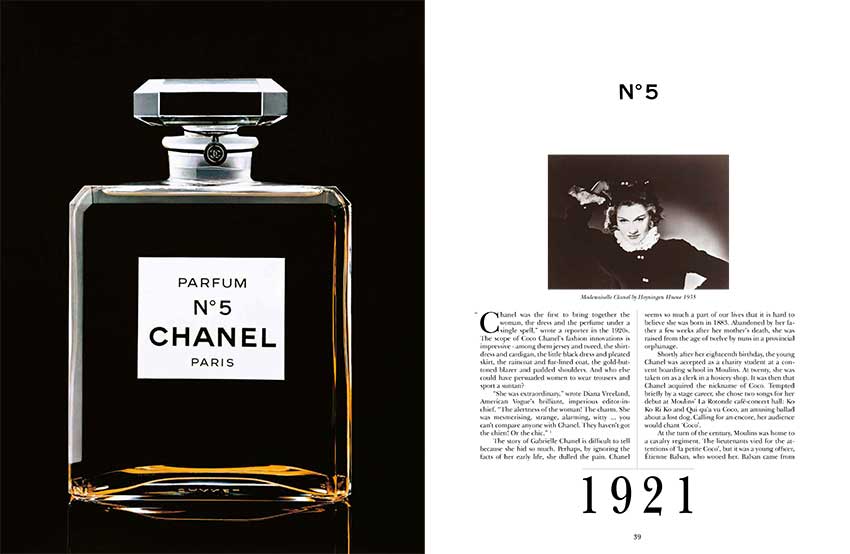

It has always been said that it was launched in 1921, but it could be 1922 after all?

Interesting isn’t it? The launch date of N°5 has long been recorded as 1921, but there is no firm evidence to support that claim. According to Yves Roubert, the original formulae were completed in March 1922. Constatin Weriguine, Beaux’s assistant, wrote that the original formulae were completed in March 1922. It is possible, then, that N° 5 was launched in 1922 rather than 1921, alongside six other perfumes of Chanel’s choosing.

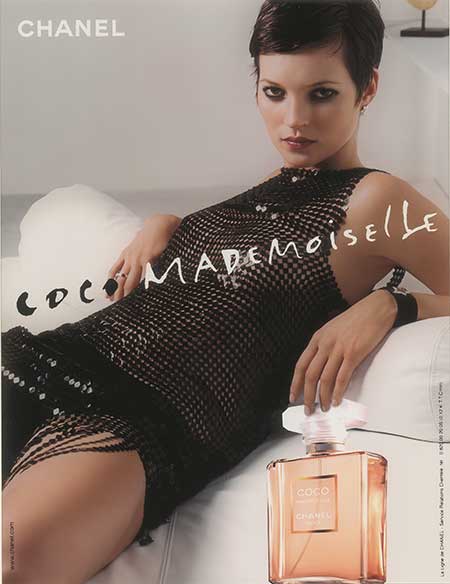

Let’s come now to Coco Mademoiselle, what prompted its birth?

Coco, the first major women’s perfume to be launched, in 1984, after the death of Coco Chanel, was in danger of being phased out of upscale department stores in the United States. Imagine the humiliation!

Flankers already existed but were not well perceived, more related to mass market?

True, but some had worked to revitalise the brand. The original Drakkar (1972) failed. But Drakkar noir, (1982) succeeded.

At that time, they were preparing the launch of Chance, that was supposed to be the big international launch?

Yes, and Coco Mademoiselle took over!

How did they came with the idea of chypre?

Jacques Polge, Chanel’s perfumer, has always admired Clinique Aromatics Elixir, a masterly chypre. But perfume moves on and patchouli replaced oakmoss as the core note in a chypre. Coco Mademoiselle was created to be the perfume Coco Chanel herself would have wear if she were turning twenty-one in the 21st century. Can you imagine Coco Chanel being a “floral-fruity” lady?

When you look back, what is a chypre? When do chypre come out? Historically, they tended to become important when women become assertive.

WW1: men died, women took over their role. Would they after the war retreat to the way it was before? No! So we saw Chypre de Coty, Mitsouko by Guerlain…

After WW2, a chypre renaissance: Bandit , Miss Dior, Femme de Rochas.

In the 1980’s, when women kick against the glass ceiling: Ysatis, Passion.

At the same time, woody orientals have become more and more important, such as Samsara (1989), but the explosion was Angel (1992). Polge clearly was aware of this influence.

They created a new trend of “neo-chypre”, also because patchouli oil could be fractionned at that time?

Yes, they had already done fractions of patchouli oil for Chance, making it cleaner, less musty, but it was used for the first time in Coco Mademoiselle.

And because it was a flanker, in many ways it was a pure recreation. All the attention was on Chance, so Polge could largely do what he wanted.

In Chance, it seems that this patchouli is used in a lighter way, it’s more facetted? But in Coco Mademoiselle, it’s more direct?

Yes, Chance is more playful, Coco Mademoiselle is more single minded, but the top notes are also very important, they give freshness and lift, which are key for the US market.

And finally Coco Mademoiselle has been an immediate success?

Yes, first in the US first, and then in the world. Today, it has overtaken N°5 to become the best selling perfume in the world.

Interview conducted on the 24th June 2019

- Buy Perfume Legends II by Michael Edwards

Comments