Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

While natural perfumery has spent many years on the margins, today a growing number of brands are laying claim to naturalness, fuelling increasing mistrust of petrochemical ingredients. Even traditional perfume brands rarely highlight any synthetic materials they may use. So why then are synthetic ingredients more useful and necessary than we think? And what exactly is green chemistry? Xavier Fernandez, professor at the Nice Institute of Chemistry, Vice-President of Innovation and Research Valorisation at Université Côte d’Azur and director of the FOQUAL (Formulation, Analyse, Qualité or Formulation, Analysis, Quality) chemistry master’s degree, shares his insights.

Why do synthetic materials need to be rehabilitated?

The tendency over the last few years has been to ostracise synthetic ingredients and glorify natural ingredients, which makes no sense. This is because, on the one hand, an untold number of poisons exist in nature. The natural materials used in perfumery, without going as far as being poisonous, are highly complex blends of organic compounds, some of them with the potential to cause allergic reactions, while a synthetic molecule is chemically defined and therefore easier to check and remove if necessary. And because, on the other hand, organic synthesis has been an inextricable part of perfumery since coumarin was used in Fougère royale, created by Paul Parquet for Houbigant in 1882. It opened the door to the production of aroma compounds identified in nature (like coumarin, which comes from the Tonka bean), but whose natural origins meant they could not meet global demand. This in turn saved dozens of species: without synthetic compounds, sandalwood and musk deer would have disappeared. Synthetic materials have also boosted perfumers’ creativity by enabling them to identify new molecules that can’t be found in nature, but that are endowed with original olfactory properties.

How do you explain the public’s distrust of synthetic materials?

Firstly because there are a lot of misconceptions. Artificial and synthetic get mixed up much too often, despite the fact that synthesis serves partially to reproduce nature – and we have to stop making consumers believe that synthetic and natural vanillins do not have the same olfactory qualities. And even though synthesis is now a safety factor for consumers, in the past certain molecules were put on the market too quickly, which feeds some people’s distrust despite there being no basis for it these days. That’s what happened with nitro musks, for example. In the late 19th century, research on explosives led to the accidental discovery that molecules with a musky odour were obtainable. It was an easy, inexpensive synthesis which produced stable results, and the musks were very popular in perfumery, including in detergents, which represented huge volumes – until it became evident that they were problematic in terms of biodegradability and toxicity. But you could say they are the exception that proves the rule: when you take into account, as we do today, the consequences on the environment and our bodies of using a molecule daily on a long-term basis, the use of synthesis is safe.

Is green chemistry, which applies sustainable development principles to chemistry, a good compromise?

There’s still a long way to go when it comes to the environmental cost of the procedures implemented, energy consumption, production of emissions and waste, and so on. Nevertheless, without succumbing to the temptation of seeing everything through green-tinted glasses, green chemistry is indeed the way forward as things stand. To draw a parallel, lots of articles explain that electric cars are actually more polluting than diesel due to the production of lithium batteries and the fact that they can’t be recycled. And while they’re certainly not perfect, there is room for electric cars to progress, unlike diesel vehicles. The same applies to green chemistry.

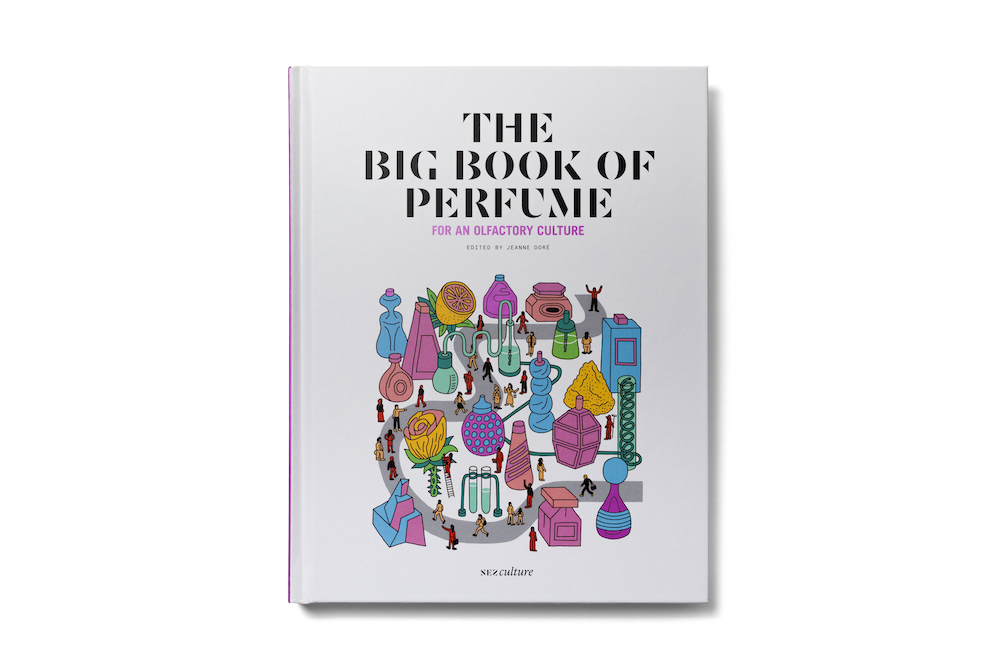

This interview is from : The Big Book of Perfume, Collective, Nez éditions, 2020, 40€/$45

- Available for France and international: Shop Nez

- Available for North America: www.nez-editions.us

Comments