Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

From the temples of antiquity to medieval synagogues, age-old mosques to modern-day churches, incense in general and olibanum – the precious resin produced by Boswellia trees – in particular have played a part in humanity’s ritual practices for thousands of years. Even though their use has been less continuous and systematic than is commonly believed. As well as the spiritual role incense has performed across the ages, especially within the monotheistic religions, it has also historically been put to more prosaic functions, such as perfuming, purifying, and repelling insects. The functional and the sacred thus intermingle in the aromatic swirls of incense smoke, reminding us that religious practices are anchored in undeniably earthly realties.

Incense covers a richly diverse range of materials and forms1Incense comprises resins, sapwood, bark, roots, leaves, flowers, seeds and animal secretions, and comes in many forms, including grains, powder, paste, tablets, cones, sticks, string and paper. (Johannes Niebler, “Incense Materials,” in Andrea Buettner (ed.), Springer Handbook of Odor, Cham, Springer, 2017, pp. 63-86. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26932-0_4.) that have been closely linked to the divine and the sacred since the dawn of time. Within certain religions, the oleo-gum-resin produced by Boswellia trees has, however, carved out a special place for itself among the many aromatic substances used by humans for spiritual purposes. Its use can be traced to the Bronze Age (circa 3200–1200 BCE) in the Near and Far East and, more sporadically, to the Iron Age (circa 1100–600 BCE) in certain parts of the Mediterranean world2Elisabeth Dodinet, “Odeurs et parfums en Méditerranée archaïque. Analyse critique des sources” [Smells and perfumes in the Archaic Mediterranean. A critical analysis of sources], Pallas, no. 106, 2018, pp. 17-41. https://doi.org/10.4000/pallas.5132.. The difficulty of obtaining frankincense, also known as olibanum, outside its native lands made it rare and all the more precious. Even so, it has always played an important role in the worship and rituals of a host of ancient civilizations3Id., “L’encens antique, un singulier à mettre au pluriel ? [Incense in antiquity, from singular to plural?], ArchéOrient – Le Blog, September 29, 2017. https://doi.org/10.58079/bcwi..

In recent years, scientists have drawn on comparisons of text sources, archaeological findings and archaeometric analyses of organic residues4Certain boswellic acids, the biochemical markers of olibanum, are identifiable even in residues dating back several thousand years, making it possible to detect resins from the genus Boswellia and sometimes even to pinpoint the species. See also research by Carole Mathe, who holds a doctorate in chemistry. to more accurately determine where frankincense has been used through the ages. We now know, for instance, that the ancient Persians, Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Sumerians, Assyrians and Etruscans5Ahmed Al-Harrasi et al., “Frankincense and Human Civilization: A Historical Review,” in Biology of Genus Boswellia, Cham, Springer, 2019, pp. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16725-7_1. used it to some extent as part of their cultural and/or funeral practices, incorporating it in balms or in the form of fumigations that, according to archaeologist Paul Faure, served to “immediately and fully enter into contact with Heaven6Paul Faure, Parfums et aromates de l’Antiquité [Perfumes and Aromatics in Antiquity], Paris, Fayard, 1987, p. 27..”

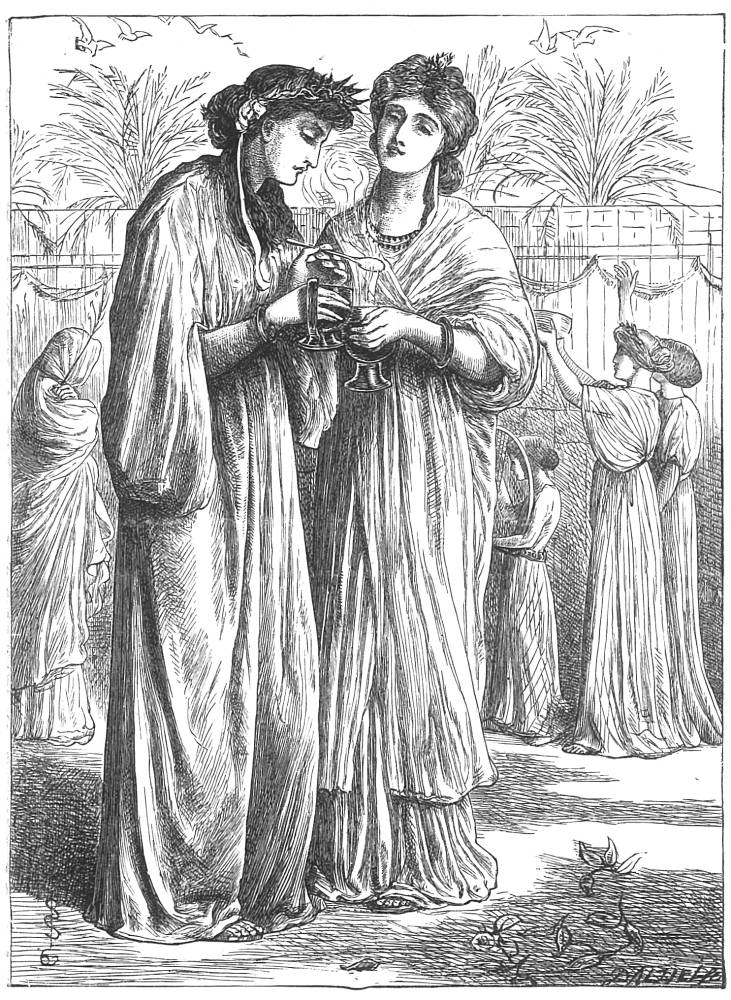

The ancient Greeks made occasional use of Boswellia resin in the same form for religious purposes7It seems that the ancient Greeks’ fascination with the Far East, which could be considered a form of proto-Orientalism, increased the appeal of olibanum’s use in Greek rites. (Mary R. Bachvarova, “Methodology and Methods of Borrowing in Comparative Greek and Near Eastern Religion: The Case of Incense-Burning,” in Robert Rollinger and Simonetta Ponchia (ed.), The Intellectual Heritage of the Ancient Near East, Vienna, Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2018, pp. 175-189.). However, since it was still very costly, it was far from the most popular incense. When it was used, it was often mixed with other more local aromatic materials, notably pine and Pistacia, which remained dominant up until the Hellenistic period8Véronique Mehl, “L’encens et le divin : le matériel et l’immatériel en Grèce ancienne” [Incense and the divine: materiality and immateriality in ancient Greece], Archimède. Archéologie et histoire ancienne, no. 9, 2022, pp. 34-45. https://doi.org/10.47245/archimede.0009.ds1.04. Olibanum remained an expensive commodity even after trade routes from southern Arabia to the Mediterranean were established in the late Classical period and throughout the Hellenistic period.. It also formed all or part of the fragrant offerings to the gods that were a regular feature of Hellenic sacrificial practices9Louise Bruit-Zaidman, “Les parfums et l’encens dans les offrandes et les sacrifices” [Perfumes and incense as part of offerings and sacrifices], in Annie Verbanck-Piérard, Natacha Massar and Dominique Frère (ed.), Parfums de l’Antiquité. La Rose et l’encens en Méditerranée, Musée royal de Mariemont, 2008, pp. 181-189., and helped to perfume shrines, giving it a role in “defining the place inhabited by divinity,” as historian Véronique Mehl describes it10Véronique Mehl, “Atmosphère olfactive et festive du sanctuaire grec : l’odeur du divin” [The olfactory and festive atmosphere of Greek shrines: the smell of the divine], Pallas, no. 106, 2018, pp. 85-103. https://doi.org/10.4000/pallas.5355..

Olibanum was also favored by the Romans, who used it for public rites in the form of libations of frankincense mixed with wine, as well as in the domestic religious ceremonies practiced by the wealthy11Marie-Odile Charles-Laforge, “Rites et offrandes dans la religion domestique des romains : Quels témoignages sur l’utilisation de l’encens ?” [Rites and offerings used in the Romans’ domestic religion: What is the evidence on the use of incense?], Archimède. Archéologie et histoire ancienne, no. 9, 2022, pp. 46-58. https://doi.org/10.47245/archimede.0009.ds1.05.. It featured in funeral ceremonies, alongside other resins, when it was used as a salve to prepare bodies, placed directly on the fire, or burned as an offering in rites worshipping the dead12Olibanum residues have been identified in a number of Roman tombs discovered in England. (R.C. Bretell et al., “‘Choicest unguents’: molecular evidence for the use of resinous plant exudates in late Roman mortuary rites in Britain,” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 53, 2015, pp. 639-648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.11.006.).

While the gradual emergence of monotheistic religions marked a fundamental shift in the way transcendence was viewed, the new creeds did retain and adapt a number of ritual practices from the older polytheistic religions they were rooted in. For instance, the Hebrew Bible, seen as the founding corpus of monotheism, emphasized the important role of aromatic substances, including olibanum, in recommended ritual practices. So what part does resin from the frankincense tree play in the texts and practices of the three major monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam?

“Seasoned with salt, pure and holy”: Hebrew incense

The Israelite religious practices in antiquity placed considerable value on fragrances13Shimshon Ben-Yehoshua, Carole Borowitz and Lumír Ondřej Hanuš, “Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead: Ancient Spices of Southern Arabia and Judea,” Horticultural Reviews, vol. 39, 2012, pp. 1-78. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118100592.ch1.. The word “incense” appears in the Old Testament (or Tanakh in Hebrew), often without specifying its nature, in around fifty verses evoking sacrifices and thuriferous oblations to Yahweh. Olibanum is, however, cited by name in the episode in Exodus (30:34-38) – one of the five books that make up the Torah – when Yahweh gives Moses a recipe for incense that is “seasoned with salt, pure and holy”: Ketoret (qětōret)14Abraham’s last wife was named Keturah (Genesis 25:1-10). comprised stacte (nataph in Hebrew, a salve sometimes thought to be myrrh, gum or styrax), fragrant shell (schechelet, sometimes regarded as the Unguis odoratus operculum or that of other gastropod mollusks15The precise nature of this particular ingredient is still the subject of much debate. While there are many advocates for the hypothesis of a fragrant product from the sea, which could explain the description of “seasoned with salt,” other researchers feel it is more likely to be a salve. If true, this would mean adding a fifth ingredient: salt.), galbanum (ħelbbinah) and “pure frankincense” (levonah zakh)16In Rabbinic literature, the Ketoret recipe is enriched with seven other ingredients, including nard, saffron, costus and cinnamon, in proportions laid out in the Talmud..

The sole purpose of holy incense was to worship Yahweh, and anyone making it for other purposes would be cut off from their people (Ex. 30:37-38). It was first used in the Tabernacle period, then in Solomon’s Temple, built in the 10th century BCE in Jerusalem, and finally in the Temple of Jerusalem built around 516 BCE to replace the First Temple, destroyed by Babylonian armies in 586 BCE. In each of these places, the wooden Altar of Incense covered in pure gold (miqṭar) was placed before the Holy of Holies (Débir) to welcome the Ketoret offering the priests (cohanim) burned there every morning and every evening.

Once a year during Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), the High Priest (Cohen gadol) would sacrifice a bull and a goat to purify the Altar of Incense with their blood (Ex. 30:10) and then burn the Ketoret in the mahtah. This object, in the shape of a small shovel and mentioned in Leviticus (16:12), among other places, served primarily to clean the menorah and transport the hot coals from the Altar of Burnt Offering, but was also occasionally used to burn Ketoret, particularly on Yom Kippur. The first person to serve as the High Priest of Israel was Aaron, brother of Moses and Myriam. Starting in the late Middle Ages, he was usually represented holding a portable incense burner symbolizing the mahtah. However, Western depictions tend to show a typically Christian incense burner with a very different shape from the ancient incense shovels used in Hebrew worship, several of which archaeologists have unearthed in Palestine17This type of Christianized incense burner also features extensively in representations of the idolatry of Solomon (1 Kings 11-12): The king, tempted by his 700 wives and 300 concubines to turn away from the one true God, took the Ketoret out of the Holy of Holies to offer the sacred incense to pagan gods, incurring the wrath of Yahweh..

Olibanum was used by itself as well as combined with other offerings, including flour, roasted ears of corn and grains, and, above all, with the offering of 12 showbread loaves18A. Van Hoonacker, “La date de l’introduction de l’encens dans le culte de Jahvé” [The date when incense was introduced to the worship of Yahweh], Revue Biblique, vol. 11, no. 2, 1914, pp. 161-187. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44101526.. God commanded Moses and his descendants to place two piles of six loaves on a golden table each Sabbath: “And thou shalt put pure frankincense upon each row, that it may be on the bread for a memorial, even an offering made by fire unto the Lord” (Lev. 24:7).

After the Second Temple was destroyed in 70 CE, Ketoret and olibanum both gradually fell out of use. While Rabbinic Jews continued to commemorate the Temple by burning incense in synagogues over the following centuries, the custom disappeared in the Middle Ages. Fumigations are no longer part of practices commonly adopted in modern-day Judaism: Only the Samaritans still use incense in their rites, particularly on the eve of the Sabbath and feast days19Abraham O. Shemesh, “Those who require ‘[…] the burning of incense in synagogues are the Rabbinic Jews’: Burning incense in synagogues in commemoration of the temple,” HTS Theological Studies, vol. 73, no. 3, 2017, a4723, p. 3. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4723. We should note that incense cannot be used on the Sabbath itself because no flames can be lit on the day of rest..

Theologians, however, continue to ask questions about the role of these substances in the ancient Priestly Code20Baholy Robijaona Rahelivololoniaina, “The Sacred Incense: The Ketoret – קְטֹ֣רֶת,” Màtondàng Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, 2024, pp. 12-28. https://doi.org/10.33258/matondang.v3i1.1045.. While there are those who assert that the fragrant smoke symbolized the prayers of the faithful rising up to God, in line with Psalm 141:2 (“May my prayer be set before you like incense”), others declare that it actually embodied the Covenant. Further hypotheses include the notion that incense smoke soothed Yahweh’s anger since it bore witness to his people’s veneration, and that the pleasant odor symbolized His perfection and/or His presence in the Temple21Deborah A. Green, The Aroma of Righteousness: Scent and Seduction in Rabbinic Life and Literature, University Park, Penn State University Press, 2011, p. 75.. In the 12th century, several theologians, including the Sephardic Rabbi Maimonides22Maimonides, The Guide of the Perplexed by Moses Maimonides, translated by M. Friedlander, Ph.D., 1904., conjectured that incense also served another, more earthly purpose: to mask the bad smells produced by sacrificing animals.

The gift of the Magi: Christian incense

Christianity, too, emerged in a geographical and cultural context where fragrances played an important role, particularly as part of religious practices. Christ’s first disciples adhered to the customs of the Temple of Jerusalem23Annick Lallemand, “L’encens et le christianisme du Ier au IVe siècle après J.-C.” [Incense and Christianity from the 1st to 5th Century CE], in Annie Verbanck-Piérard, Natacha Massar and Dominique Frère (ed.), op. cit., pp. 335-342. and the Ketoret offering was described anew in the New Testament: In the Gospel of Luke (1:5-13), Zacharius, married to Elizabeth, who was a descendant of Aaron, was offering incense to Yahweh “according to the custom of the priest’s office” when the angel Gabriel appeared on the right side of the Altar of Incense and told him his barren wife would give birth to a son he was to name John.

The symbolic importance of incense in the Gospel resides primarily in the scene where “the Magi from the East” worship the newborn, as recounted in the Gospel of Matthew (2:11-12). This episode, described in more detail in the Apocrypha, features resin from the Boswellia tree as one of the three precious gifts offered to Baby Jesus. Although theologians have put forward many symbolic interpretations of these gifts, it is generally acknowledged that gold stands for the child’s royal status, myrrh – bitter and widely used for embalming – represents his humanity, while frankincense testifies to his divine nature24Several commentators believed that the third gift was not gold in the way we understand it but had been wrongly translated or misinterpreted, and was actually a different aromatic, possibly a spice or another yellow-colored resin. Thus, including red myrrh and white frankincense, Baby Jesus would have received three different colored aromatic substances. (Paul Faure, op. cit., p. 96; Susan Ashbrook Harvey, Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2006, p. 33)..

Nevertheless, the use of incense, pure or in compounds, was soon forbidden within Christianity to draw a distinction with Roman and Jewish customs25Starting in the early 2nd century, the refusal to burn incense before images of the emperor was a sure way of identifying a Christian, usually resulting in expulsion, persecution or execution. (Annick Lallemand, op. cit., pp. 339-340).. God “has no need of streams of blood and libations and incense26Saint Justin, Apologies, transl. by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. https://www.logoslibrary.org/justin/apology1/13.html.,” wrote Justin Martyr in the 2nd century. A number of Church Fathers, such as Tertullian, strongly condemned the use of aromatic substances, associated with paganism and apostasy, while other apologists, such as Origen and Athenagoras, went even further, deeming them to be food for demons27Sophie Read, “What the Nose Knew: Renaissance Theologies of Smell,” in Subha Mukherji and Tim Stuart-Buttle (ed.), Literature, Belief, and Knowledge in Early Modern England, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, p. 179..

Incense did not carve out a symbolic place for itself in Christian liturgy until after Roman co-emperors Licinius and Constantine I granted Christians religious freedom in 313 CE. In the late 14th century, incense was reintroduced into Christian churches as part of funeral rites. As historian Béatrice Caseau notes, it was initially used “around graves, including the tomb of Christ himself as well as those of the martyrs or their reliquaries28Béatrice Caseau, “Encens et sacralisation de l’espace dans le christianisme byzantin” [Incense and sanctification in the world of Byzantine Christianity], in Yves Lafond and Vincent Michel (ed.), Espaces sacrés dans la Méditerranée antique, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2016, p. 264..” Catholic and Orthodox funerals always concluded by burning incense over the coffin during Absolution, symbolizing the prayers that accompany the deceased and marking their entry into “the pleasing aroma of Christ” (2 Corinthians 2:15)29Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Hebrew, Christian and Muslim civilizations have all attributed their gods – as well as, oftentimes, the gods’ emissaries and servants – with a pleasant aroma, associating a pure soul with a good smell. Christians also saw the transformation of resin from a tangible material substance into aromatic, intangible smoke as a symbol of the body becoming spirit..

Over the centuries, incense-burning practices based on olibanum, pure or mixed with other substances30It seems that Christians favored the use of resinous substances in their practices due to their imperishable nature. Chemical analysis of Christian incense burners dating from the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries and discovered in modern-day Belgium revealed the presence of olibanum from South Arabia alongside other local ingredients, including juniper and pine resin. (Jan Baeten et al., Holy Smoke in Medieval Funerary Rites: Chemical Fingerprints of Frankincense in Southern Belgian Incense Burners, PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 11, 2014). Catholic priests in the New World received a papal dispensation allowing them to use resin from local sources, such as copal, rather than olibanum. (David M. Stoddart, The Scented Ape: the Biology and Culture of Human Odour, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 194). Today’s highly sought-after “pontifical” incense is a blend of frankincense, myrrh, benzoin and styrax., gradually become more widespread in Christian liturgy, with different degrees of intensity depending on where they were observed and whether Eastern or Western traditions held sway there31Catherine Gauthier, “L’encens dans la liturgie chrétienne du haut Moyen Âge occidental” [Incense in Christian liturgy in the Middle Ages], in Annie Verbanck-Piérard, Natacha Massar and Dominique Frère (ed.), op. cit., pp. 343-349.. During mass, processions and other Catholic, Orthodox and apostolic celebrations, different types of incense burners served to circulate the sweet smoke, which became a “performative sign32Margaret E. Kenna, “Why Does Incense Smell Religious?: Greek Orthodoxy and the Anthropology of Smell,” Journal of Mediterranean Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, 2005, pp. 51-70.” of transcendence. The smell of incense performed a vast array of symbolic functions that evolved and became more elaborate over the years, serving as a placatory offering, sign of benediction, remedy against the devil, manifestation of the presence of the Holy Spirit and vehicle accompanying prayers. However, the Reformation in the 16th century saw Protestants rejecting these functions and restraining the use of incense, once again seen as representing the sacrificial practices of Judaism.

In the same way that Ketoret was meant to mask unpleasant fumes floating in the air of the Temple, sacred smoke filling Christian places of worship also fulfilled more prosaic functions. Starting in the Middle Ages, incense was valued for its prophylactic and therapeutic properties as well as serving to purify the air where miasma could circulate and mask the exhalations of the bodies gathered in the church (as well as those of any bodies buried beneath the feet of the living33Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: an analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo, London, Routledge, 1966, p. 30; Sophie Read, “What the Nose Knew: Renaissance Theologies of Smell,” in Subha Mukherji and Tim Stuart-Buttle (ed.), Literature, Belief, and Knowledge in Early Modern England, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, p. 182.). As historian William Tullett recounts, in the late medieval period, sermons on the Epiphany taught Christians that “the frankincense offered by the Three Kings as a gift to the child counteracted the stench of the stable in which it was found34William Tullett, Frankincense, Encyclopedia of Smell History and Heritage [online], published June 14, 2023..“ Ensuring that the church smelled good thus served to protect the health and guarantee the olfactory comfort of the faithful. As a result, in the 19th century, a number of Protestants, particularly Anglicans, demanded that incense be reintroduced into their places of worship35Thanks to the English theological and ecclesiastic Oxford Movement that emerged in the 1830s, incense was once again given a role in what was called the Anglican High Church..

From Athos to Solan: Incense in Orthodox monasteries

The liturgy of the Orthodox Church is often described as “synesthetic36Margaret E. Kenna, op. cit., p. 63.” since it calls on all the senses. It is perhaps understandable, then, that Orthodox Christians continue to use incense on a massive scale today. “Incense is used far less in the Catholic world than by us Eastern Orthodox Christians,” explains Sister Yossifia from the Solan monastery in the Gard, southern France, where incense is burned at almost every office: at the beginning of matins, to accompany the Magnificat and punctuating daily mass. “The modernization of worship has forgotten about incense as well as the sensory aspect of prayer,” says Sister Yossifia regretfully. The community of women at the monastery sells natural incense they produce themselves in quantities of around 100 kilos a year. The nuns learned the technique in an English monastery, whose members had been taught it directly by monks from Mount Athos in Greece, at the heart of Orthodox spirituality. Athonite incense derived from the recipe given to Moses in Exodus usually contains a base of frankincense and myrrh with the addition of other resinous or floral materials37Aaron Stevens, “The Smell of Holiness: Incense in the Orthodox Church,” Mt. Menoikeion Seminar, June 15, 2016. https://menoikeion.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf2036/files/stevens-paper.pdf.. For example, the Solan nuns add cedar resin purchased in Greece or Turkey alongside essences from Grasse. “Balsamic aromas containing orange blossom and myrrh as well as essences of rose, jasmine, honeysuckle, orange blossom, gardenia, lily, and so on,” says Sister Yossifia, explaining that the community adapted a baker’s kneading machine to form the incense paste: “The resins do the work of the flour and the essential oils do that of water.” They then shape small grains by hand and coat them in magnesium powder to preserve them. After that they are ready to be placed on hot coals so they can release their scent and perfume the different moments of worship.

Secular rather than sacred: Muslim incense

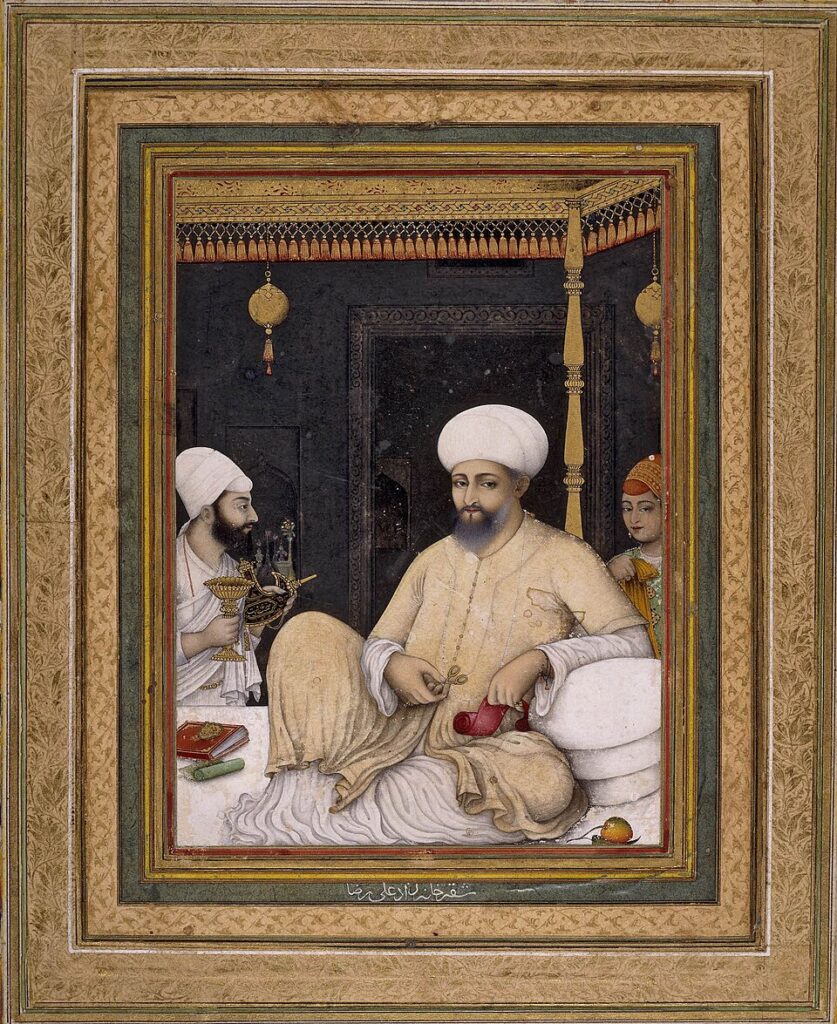

While the use of incense in the Arab world during the pre-Islamic period – until around 622 CE – was an essentially ritual custom, no writings seem to expressly associate fragrant smoke with the act of worship in the Islamic world. Incense burners were not a regular feature of mosques, or only very rarely38Julie Bonnéric, “Réflexions sur l’usage des produits odoriférants dans les mosquées au Proche-Orient (ier/viie-vie/xiie s.)” [Reflections on the use of aromatic products in Near Eastern mosques (1st/7th-6th/12th centuries)], Bulletin d’études orientales, T. 64, 2015, pp. 293-317.. While evidence of a few rare uses of incense in a religious context does exist, the many secular uses of incense, including olibanum (lubān), starting in the medieval period, are far better documented. And although Arab terminology from the time can make it difficult to accurately identify the fragrant substances mentioned in texts, especially since some of them were used by themselves, such as olibanum, benzoin and bdellium, but also in blends like nadd, a medieval Arab incense comprising mostly olibanum, ambergris and musk39Nigel Groom, The Perfume Handbook, Dordrecht, Springer, 1992, p. 157. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-2296-2.. Despite these difficulties, we know that resin from the Boswellia tree was widely used in the form of fumigations by early Muslims, principally for its prophylactic properties and the pleasures it procured, to perfume bodies, clothes and spaces, and as part of domestic and princely hospitality rituals40Sterenn Le Maguer-Gillon, “The art of hospitality: incense burners and the welcoming ceremony in Medieval Islamic society (7th-15th cent.),” in Jean-Alexandre Perras and Érika Wicky (ed.), Mediality of Smells / Médialité des odeurs, Berne, Peter Lang, 2021, pp. 41-59.. The markedly secular practices of burning incense that then played, and still play, such a large part in daily life for Arab Muslims do not have much of a connection to the sacred within Islam41Only four aromatics are specifically cited in the Quran: “the aromatic plant” (rayhān ), camphor (kafūr), ginger (zanjabīl) and musk (misk). The hadiths, accounts of the oral tradition of anecdotes relating to the Prophet Muhammad, testify to his penchant for fragrances, but frankincense is not among the substances he favored; he preferred oud and camphor. (Sterenn Le Maguer-Gillon, “L’encens dans le monde islamique médiéval (VIIe-XVe siècles) : usage sacrés, usages profanes” [Incense in the medieval Islamic world (7th-15th centuries): sacred uses, secular uses], in Béatrice Caseau and Elisabetta Neri (ed.), Rituels religieux et sensorialité (Antiquité et Moyen-Age), Cinisello Balsamo (Milan), Silvana Editoriale, 2021, pp. 463-474.).

While it seems that fragrant substances (mainly oud rather than olibanum) were occasionally burned in the medieval period in a number of mosques, during prayers and Ramadan, as well as at the Kaaba in Mecca, they nevertheless had no symbolic value and simply ensured places were pleasantly scented42A further hypothesis suggests that fumigations might also have fulfilled a practical purpose: repelling insects such as flies and mosquitoes, thanks in particular to the linalool contained in frankincense resin (Ahmed Al-Harrasi et al., op. cit., p. 6).. Furthermore, proof of these practices remains anecdotal, which, as archaeologist and medieval Islam specialist Julie Bonnéric notes, may well point to a desire to set mosques apart from “secular buildings such as houses and palaces, as well as other religious edifices, including churches and synagogues, where the abundance of fragrances burned or applied there created an overwhelming odor43Julie Bonnéric, “Entre fragrances et pestilences, les odeurs en terre d’Islam au Moyen Âge” [From fragrances to pestilences, studying odors in the lands of Islam in the Middle Ages], Bulletin d’études orientales, T. 64, 2015, p. 37..” She feels that the absence of complex rituality in Muslim worship could also explain this restrained use of incense in the mosque. Nevertheless, as Arab philology specialist Jean-Charles Ducène writes, “it does seem that the smoke slowly made its way into certain forms of devotion44Jean-Charles Ducène, “Des parfums et des fumées : les parfums à brûler en Islam medieval” [Perfumes and smoke: fragrances for burning in medieval Islam], Bulletin d’études orientales, T. 64, 2015, p. 171.,” particularly within Sufism, i.e., the esoteric and mystical practices of Islam that seek purification of the soul. For instance, incense (bakhūr) was burned in zawiyas45Religious building at the heart of a Sufi community. during dhikr46The term denotes both the memory of God and the practice that honors that memory. Dhikr plays a central role in Sufism and involves repeatedly reciting prayers or holy phrases out loud or in a whisper, often in a group, producing an almost trance-like state. to accompany prayers and litanies and facilitate contact with the spiritual world, foster contemplation and drive out evil spirits47Sterenn Le Maguer-Gillon, “L’encens dans le monde islamique médiéval (VIIe-XVe siècles) : usage sacrés, usages profanes” [Incense in the medieval Islamic world (7th-15th centuries): sacred uses, secular uses], op. cit. Fumigations were also an essential part of magical practices. For instance, they made it easier to communicate with djinns and spirits and were used in exorcisms. However, even though these rituals laid claim to the Muslim religion, the religious authorities could on occasion strongly condemn them.. In Indonesia, where Islam was introduced by Sufi traders around the 13th century, the encounter between the newcomers’ ritual fumigation practices and the incense-burning habits of traditional societies paved the way for local people’s acculturation to Islam48Mohammad F. Royyani et al., “Incense and Islam in Indonesian context: An ethnobotanical study,” Ethnobotany Research and Applications, vol. 28, pp. 1-11. https://ethnobotanyjournal.org/index.php/era/article/view/5511.. Even though it was considered a heretic practice, particularly by certain orthodox Muslims who arrived in the 19th century, many Indonesian Muslims continue to burn incense to this day, sometimes blending resin from the Boswellia tree with other more local substances49The exact composition of the fragrances used for burning within Sufism and the traditions they created remain difficult to identify. While they did feature resin from B. sacra as well as B. frereana (known as “Coptic incense”), other local and exotic substances seem to have played a more dominant role..

From the polytheistic religions of antiquity to their ever-flourishing monotheistic successors, frankincense (olibanum) has journeyed through the ages and forms of worship in the rituals of ancient Judaism, Christianity and, more marginally, Islam. Nonetheless, its use for religious purposes over the last 2,000 years is not as linear and universal as we might think. Depending on the period and doctrinal variations within these religions, frankincense has gone from sacred to secular and back again, oscillating between liturgical instruction, distrust and prohibition, shifts that reveal contrasting relationships to ritual and olfactory symbolism.

It is interesting to note that the spiritual role incense has played over the centuries existed alongside more prosaic motivations for its use: perfuming enclosed spaces, masking the odors of flesh, disinfecting places and repelling insects. The functional and the sacred thus intermingle in the aromatic swirls of smoke we associate with monotheistic religions, reminding us that religious practices are anchored in undeniably earthly realties.

Main illustration : Salvador Viniegra y Lasso de la Vega, La Bendición del campo en 1800, 1887. (source : Museo de Málaga)

Comments