Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Should we say “ambery” or “oriental”? In the first part of this series, we questioned the perfume theorists and their use of the term “amber” to deal with the purely olfactory dimension of perfume. However, this cannot be disconnected from a metaphorical dimension which has become more complex since the 19th century due to the success of Orientalism and the aestheticization of the colonial imagination.

To formulate the Orient: Perfumery and Orientalism

In his book Orientalism, Edward Said discusses the narrative on the “Orient” produced by Western writers and artists in past centuries. But what is the Orient? Since there is no geopolitical entity bearing that name, Said’s work describes it as a protean space seen from the viewpoint of the West, made up of the Middle East, part of Africa, Southeast Asia and the Far East. These places are considered at a certain mythical moment in their development, when they were neither influenced by Western colonialism nor reformed by the Muslim clergy. We can thus understand the position of Serge Lutens, who sought to get his perfumery out of the mythological vagueness and preferred to speak of “Arab” rather than “Oriental” perfumery.

Orientalism is a thought based on the ontological distinction between East and West. Many writers, poets, novelists and philosophers have used this fundamental distinction as the starting point for elaborate theories, epics, novels, social descriptions and political accounts concerning the Orient, its people and customs, its “spirit” and its destiny. [1]Edward Said, Orientalism, op. cit., p. 2-3.

“Orientalists” have never considered it their duty to give voice to the foreigners they observed: They focused on reporting on their situation from their Western point of view and tried to “domesticate”[2]Ibid., p. 78. exoticism. For Edward Said, Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt in 1798 marked the establishment of the new Orientalist movement, as the future emperor proclaimed his desire to restore the region from “its present barbarism to its former classical greatness” and “to formulate the Orient, to give it shape, identity, definition with full recognition of its place in memory, its importance to imperial strategy, and its ‘natural’ role as an appendage to Europe.”[3]Ibid., p. 86. Orientalism emerges here from a severe power struggle.

“To formulate the Orient” is a seductive statement that could also sum up part of the career of perfumer Jacques Guerlain (1874-1963). In 1925,[4]Michael Edwards, Parfums de légende, translated by Guy Robert, Levallois-Perret, HM éditions, 1998, p. 55. he created Shalimar, a perfume that marked a turning point in history and launched a new fashion in perfumery, particularly fond of the Orient. Jacques Guerlain had probably never visited Asia, but his passion for the Orient as an idea led him to draw inspiration from the history of the Taj Mahal and the gardens of the Emperor Shah Jahan. In Shalimar, vanillin is associated with benzoin, coumarin and labdanum, the key ingredients of “ambery” compositions. However, his Oriental taste is not always reflected in creations belonging to this olfactory family. The perfume Kadine, released in 1911 and reissued in 2021 by Guerlain, is a lesson in this respect: Its name of Turkish origin means “sultan’s wife,” but its majestic composition is indeed floral, with aniseed and bergamot making a bed for heliotrope, jasmine, iris and violet. The terms “amber” and “Oriental” are therefore not substitutable for each other in the history of perfumes.

The two sides of the colonial coin

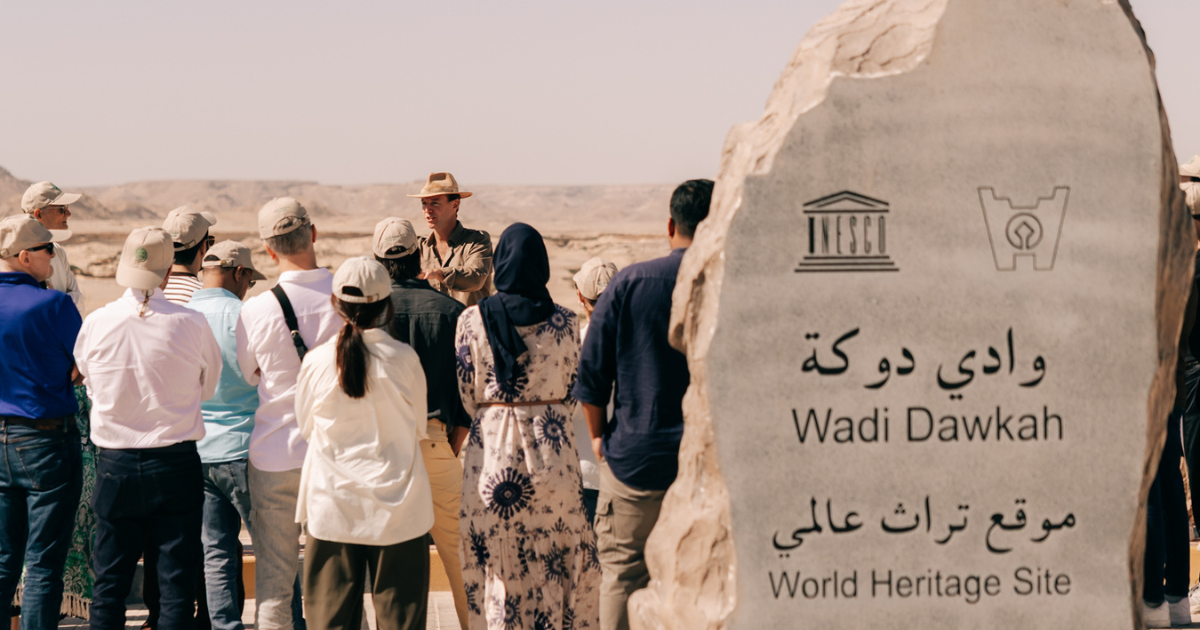

The perfumer’s palette expanded drastically in the 19th century, thanks to synthesis but also to the colonial conquests of the areas where natural raw materials were cultivated or harvested. Unsurprisingly, most of these came from the same lands that gave birth to Orientalist imagery. The cartography of natural raw materials proposed in The Big Book of Perfume[5]Jeanne Doré (ed.), The Big Book of Perfume, Paris, Nez éditions, 2020, p. 54-55. is emblematic in this respect: It reveals the interest in products collected along the colonial routes that spread out from Europe and draws the map of the “Orient” by evoking ingredients like incense bought in Oman, cedar from North Africa, sandalwood from India, oud from Southeast Asia or ginger from China.

Most of these natural raw materials are of wild origin: They are harvested by local populations that the market refuses to take into consideration, even when it is the source of technical innovations. The process of fertilizing vanilla, for example, was discovered around 1841 by Edmond Albius, who was reduced to the rank of slave on Bourbon Island (now Réunion Island).[6]Hélène Blais & Rahul Markovits, “Le commerce des plantes, XVIe-XXe siècle”, Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine, 2019/3, n° 66-3, online : … Continue reading The current decay of Somalia, whose frankincense is sold at a premium price, or of Madagascar, whose vanilla has been used all over the world since the end of the 19th century, still bears witness to the violence of the colonial extraction of raw materials, while the wealth generated by the production never went back to the local workers – a situation that continues to give rise to many tensions.[7]Nancy Kacungira, “Fighting the vanilla thieves of Madagascar”, BBC.com, August 16, 2018, online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/madagascar_vanillla (accessed on 03/01/2022). In the colonized lands, the European quest for ores and raw materials also had tragic ecological consequences, as is the case in South India, in the Western Ghats, where the British forestry policy led not only to the exploitation of the population but to the deforestation of a significant part of the territory.[8]Jacques Pouchepadass, “Colonisation et changement écologique en Inde du Sud. La politique forestière britannique et ses conséquences sociales dans les Ghâts occidentaux (XIXe-XXe siècles)”, … Continue reading

“The colonial nightmare is, however, masked in old Europe by the Oriental dream and the creative enthusiasm it arouses. The hard work that goes on far away generates the most brilliant leisure and art in the West. For the re-release of Kadine, Guerlain recalled in its communication the Orientalist intention of Jacques Guerlain, and his links with the Parisian fashion of the time. As he was working on the perfume, in 1910, the Opéra de Paris was indeed performing Shéhérazade for the first time, with Michel Fokine’s choreography for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes on the music written by Rimsky-Korsakov. At this time, Orientalism was one of the last relics of a Romanticism that did not seem to want to end, with its clichés, its fantasies, its detachment from the material history of the world and its vagueness in which India, Turkey and China were indistinctly mixed. As fashion allows it to come back in the late 20th century, it continued to inspire Yves Saint Laurent in 1977: “Even today, everything in Europe that is modern in music, in color, in art, has been based on Orientalism,” explains the creator of Opium to André Léon Talley,[9]André Léon Talley, “YSL on Opium”, Women’s Wear Daily, New York, USA, September 18, 1978. announcing a new revival of the theme by the perfume industry.

The fixation of the Orient in discourses and forms

In his work, Edward Said pinpoints the ideological problems posed by Orientalism: Essentially ambiguous, it is both a “knowledge” (about hieroglyphs or perfumery plants, for example) and an “imagination,” discursively constructed for centuries by “the Occident” about “the Orient.” This mix produces a certain number of very profitable false evidences and a position of power: Unequal relations are justified and framed by the Orientalist discourse.

By defining the Other that the Orient represents, the Occident has also been able to define itself. The Orient, a designated cultural rival, reflects an image of the old continent, a personality and an experience that are in contrast, even opposed, to how it saw itself. In this respect, the Orient is a true “integral part” of European civilization. While it has crossed the centuries, it remains a particularly stable imagination and is presented as “fixed” by the West: The narrative that surrounds it is essentially made up of constant reworkings of previous discourses.[10]Regarding this “reiterative transhistoricity” characteristic of ideology, one can read Patrick Tort, Qu’est-ce que le matérialisme ?, Paris, Belin, 2016, p. 38. The people it designates are thus also locked into a “fixism” that uniformly attributes to them a name (the “Orientals”) and characteristics that sometimes present themselves in the form of “racist clichés” used to define a lesser breed of human beings.[11] Edward Said, Orientalism, op. cit., p. 341. This explains and justifies the contemporary mistrust of the notion, particularly among Anglo-Saxons who kept on designating entire populations with the word “Oriental.” As an intellectual, aesthetic and political construction, the Orient does not exist in and for itself, but for the use of the Occident, and it is most often presented as an eternal land of subalterns.

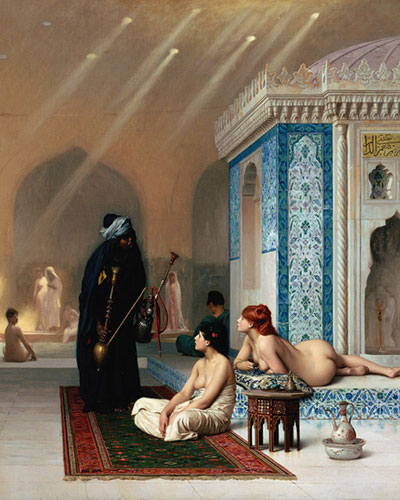

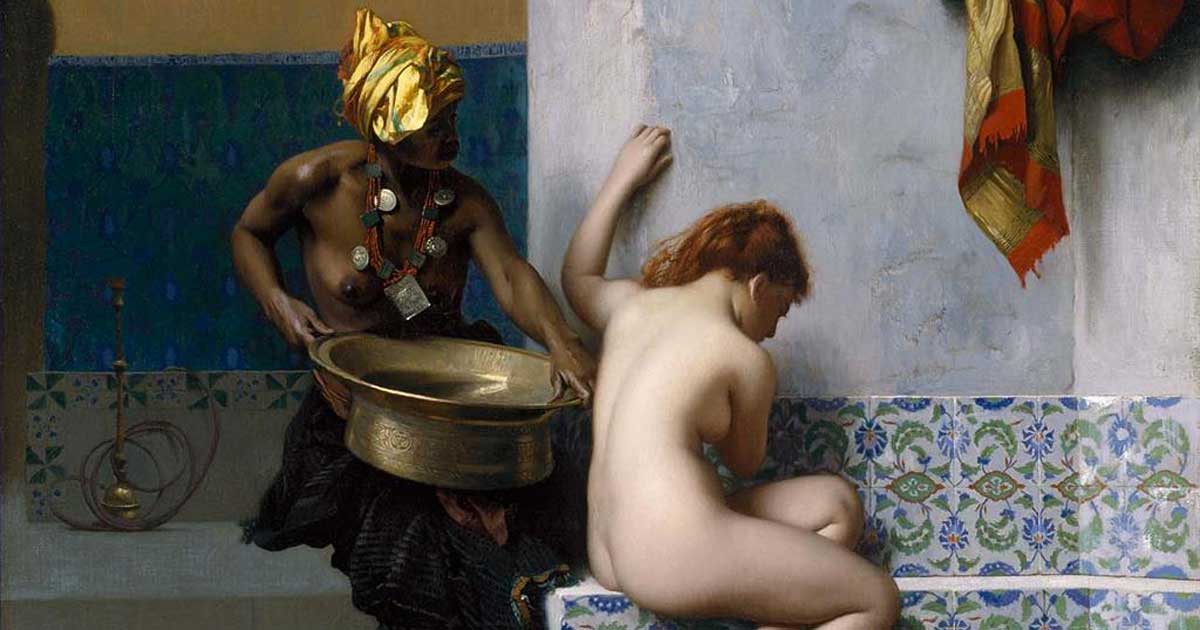

Aesthetically, Orientalism does not seek to camouflage “fixism,” but rather plays with the motifs it repeats, with fables whose renewed evocation reinforces the feeling of authenticity. The reinterpretation of the same imagery is thus particularly noticeable in the paintings of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), such as Pool in the Harem in 1876, which presents an idealized intimacy,[12] For further insights on this subject, see: Linda Nochlin “The Imaginary Orient” in The Politics of Vision, New York, Routledge, 1989. and already contains many of the visual codes that we see extended during the 20th century.[13]An analysis of this aesthetic is presented by Ma Lin in “The Representation of the Orient in Western Women Perfume Advertisements: A Semiotic Analysis”, Intercultural Communication Studies, XVII, … Continue reading It is still this reworked imagery that is proposed by Guerlain in its recent communication campaigns around Shalimar. Repetition does not harm the reception of Orientalist aesthetics, on the contrary: It creates the Orient as a commonplace that is welcoming and reassuring in its constancy, offering a reverie that no bad surprise can disturb. The phenomenon can be observed even in scents, when aficionados of “Oriental fragrances” take pleasure in rediscovering with each perfume how one of the most stable forms of perfumery is worked, with its warm heart of vanilla and benzoin, whose spicy coating does not even change much over time.

The Orient, between aesthetics and politics

What should be done with Orientalism in light of these contradictions? Should it still be given some praise or should it be denounced? Edward Said urged his readers not to misunderstand his subject: “Nowhere,” he wrote, “do I argue that Orientalism is evil, or sloppy, or uniformly the same in the work of each and every Orientalist. But I do say that the guild of Orientalists has a specific history of complicity with imperial power, which it would be Panglossian to call irrelevant.”[14] Edward Said, Orientalism, op. cit., p. 342. In many cases, artists and perfumers reflect the society of their time, so it is up to us to be aware of their achievements, but also of the function they may have had in the formation of Orientalist knowledge, and the imperialist oppression that went with it.

At the same time, our judgment on the old Orientalism that perfumery still represents deserves to be weighted, particularly by taking into account its political and social influence, which is now insignificant compared to that of another Orientalism denounced by Said. The author makes a distinction between the “pre-Romantic, pre-technical Orientalist imagination of late-nineteenth-century Europe,” which conveys the “free-floating Orient” that is still the one used in perfumery, and “academic Orientalism,” “modern Orientalism,”[15]Ibid., p. 119. whose political effects have been more directly devastating, both in the 20th century and today. The real targets of Said’s attacks are thus “Orientalists who betrayed their calling as scholars,”[16]Ibid., p. XV. such as Bernard Lewis and Fouad Ajami, whose work influenced U.S. foreign policy in the early 21st century, including George W. Bush’s military interventions in the Middle East, contributing to a revival of postcolonial dynamics.

Orientalism therefore needs to be re-evaluated and demystified: Relations of power and domination cannot be addressed solely by a transformation of vocabulary. The suppression of the term “Oriental” is not able to prevent the reproduction of the tragic dynamics that we have described, both by brands and by perfumers who have, sometimes in spite of themselves, preserved from this forgotten past a certain culture of inequality and “rebranded” authoritarian structures. In contrast to all the dynamics of oblivion, it is undoubtedly preferable to preserve the olfactory culture and the knowledge of its history, which includes all its asperities, the contradictions that have shaped the world in which we live. We must also be aware that if “ambery” or “Oriental” perfumery is the aesthetic summit that we know, it is not due to a few conquering Western elites, but thanks to a myriad of actors that the history of perfume often struggles to take into account.

Reorienting perfumery?

In the contemporary communication of perfumery, the discourse on Orientalism already seems to have evolved. The re-release of Kadine is exemplary in this respect: Guerlain does not insist on the Turkish or Indian traditions in its discourse, but on the cultural ferment of the “Belle Époque” that Jacques Guerlain knew, now irretrievably lost. At the time, people were dreaming of the Orient in theaters and department stores, and fables about this strange and desirable world were particularly lively. In contemporary advertising, nostalgia for this Orientalist moment seems to have overtaken the dream of the Orient itself, while more and more brands seem to be banking on the fact that Oriental perfumery perhaps speaks to us more of another time than another space. They seem to play on the memory of the glory days of European high society that entertained itself with fantasies that our contemporaneity has since somewhat emptied.

Perfumers also take a central place in the communication. Their names were barely known a few years ago, but now they have a greater say than ever. At the same time, many contributors to the perfume industry remain anonymous, even though perfume is becoming more and more a co-creation. Evaluators, sourcers, inventors of synthetic raw materials, but also horticulturists, farmers, pickers, cultivators from six continents: All these are not less crucial or more dispensable links, even if the myth of the Orient and the capitalist structure of our society attribute a different prestige to them.

While many composition houses now offer programs to support farmers to improve their situation, the global market is still shaped by colonialism, and the palliatives that are deployed (such as the construction of schools or promises of a fair price for their harvest) are insufficient to bring about egalitarian trade between the West and former colonies. Edward Said was fighting to avoid waging war on the subalterns who have been called “Orientals,” and the critique of Orientalism cannot be carried out without this idea, without making a fair place for the most fragile participants in the perfume industry. Their past, their aesthetic contribution is no less rich and interesting: Many farmers’ lives and olfactory productions from villages of gatherers are worth more than Oriental legends that have been dulled by marketing.

Contemporary debates remind us that the curious stability of olfactory aesthetics makes perfumery a privileged witness to the passage of time. This dimension, far from being a hindrance to our aesthetic enjoyment, gives us the opportunity to make perfume not only a source of pleasure, but also a witness to history, a moment of awareness of the world’s progress. Oscillating between scents and metaphors, olfactory culture gives us the opportunity to smell as well as to dream and think, and should be able to teach us about aesthetic joys as well as historical events.[17]For further reading on the subject, see: Karl Schlögel, The Scent of Empires: Chanel N° 5 and Red Moscow, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2021. As such, Shalimar is not only “ambery,” it is also an “Orientalist” perfume, if not an “oriental,” with all the contradictions that this implies, all the rich narrative of the relations between Europe and the rest of the world that it underlies.

As I examine once again the original French version of this article in order to translate it into English, the version you are now reading, I am still struck by how different is the meaning of the term “Oriental” in English and in French, but how advertising, marketing companies and commentators tried to use it in a similar way in both languages in the 20th-century perfume world. This article is just the sketch of research that needs to be extended, but I wouldn’t be astonished if we were to find out that another part of the contemporary controversies come from a certain laziness in translating terms from French into English (and from an overall laziness that makes “Oriental” sound like an efficient description for smells in general). We have to keep in mind that the history of the term “Oriental” in French and in English is quite different. That’s probably another useful lesson: The Occident also isn’t as unified as we’d want it to be; our language and the way we perceive it bear the mark of different histories.

Nevertheless, the real challenge for the perfumery of today is perhaps not to make a “better” Orientalism (even if that were possible) or to propose the old Orientalist aesthetic under a different name (which is sometimes already the case), but to make a contemporary perfumery inhabited by a real diversity, leaving behind the “fixisms” of the past.

Notes

| ↑1 | Edward Said, Orientalism, op. cit., p. 2-3. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid., p. 78. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., p. 86. |

| ↑4 | Michael Edwards, Parfums de légende, translated by Guy Robert, Levallois-Perret, HM éditions, 1998, p. 55. |

| ↑5 | Jeanne Doré (ed.), The Big Book of Perfume, Paris, Nez éditions, 2020, p. 54-55. |

| ↑6 | Hélène Blais & Rahul Markovits, “Le commerce des plantes, XVIe-XXe siècle”, Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine, 2019/3, n° 66-3, online : https://www.cairn.info/revue-d-histoire-moderne-et-contemporaine-2019-3-page-7.htm?contenu=article (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑7 | Nancy Kacungira, “Fighting the vanilla thieves of Madagascar”, BBC.com, August 16, 2018, online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/madagascar_vanillla (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑8 | Jacques Pouchepadass, “Colonisation et changement écologique en Inde du Sud. La politique forestière britannique et ses conséquences sociales dans les Ghâts occidentaux (XIXe-XXe siècles)”, Revue française d’histoire d’outre-mer, Vol. 80, n° 299, 1993, p. 165-193. Online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/outre_0300-9513_1993_num_80_299_3087 (accessed on 03/01/2022). |

| ↑9 | André Léon Talley, “YSL on Opium”, Women’s Wear Daily, New York, USA, September 18, 1978. |

| ↑10 | Regarding this “reiterative transhistoricity” characteristic of ideology, one can read Patrick Tort, Qu’est-ce que le matérialisme ?, Paris, Belin, 2016, p. 38. |

| ↑11 | Edward Said, Orientalism, op. cit., p. 341. |

| ↑12 | For further insights on this subject, see: Linda Nochlin “The Imaginary Orient” in The Politics of Vision, New York, Routledge, 1989. |

| ↑13 | An analysis of this aesthetic is presented by Ma Lin in “The Representation of the Orient in Western Women Perfume Advertisements: A Semiotic Analysis”, Intercultural Communication Studies, XVII, N° 1, 2008, p. 44-53. |

| ↑14 | Edward Said, Orientalism, op. cit., p. 342. |

| ↑15 | Ibid., p. 119. |

| ↑16 | Ibid., p. XV. |

| ↑17 | For further reading on the subject, see: Karl Schlögel, The Scent of Empires: Chanel N° 5 and Red Moscow, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2021. |

Comments